|

CG-4A Glider |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Glider Pilot - MOS (Military Occupational Speciality) 1020 |

|

|

American 15 Place Waco CG-4A Glider Used at Atterbury AAF The concept of the combat glider can be traced to the outcome of World War I. Under the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was forced to reduce its land army to a token 100,000 men and was prohibited from having an air force. Since the treaty did not prohibit the building and flying of gliders, glider-flying clubs sprang up throughout Germany. Within eight years after the war ended, German high schools were offering glider flying as part of their regular curricula. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, the young men trained in gliders helped to form the core of the new German air force, the Luftwaffe. Hitler himself perfected the strategy of landing assault teams behind enemy lines, both day and night, in engineless aircraft. (Russia pioneered in this area with cargo gliders, though its gliders as troop carriers were never used in combat. However, after the war, Russia maintained three glider-infantry regiments until 1965.) The first German combat glider, designated the DFS230, had a wingspan of 72 feet and fuselage 38 feet long. The first use of this aircraft took place on May 10, 1940. In the half-light of dawn, shortly after 5 a.m., ten 230s carrying a total of 78 assault troops swooped down and landed on top of a huge Belgian fort, Eben Emael, a barrier to Hitler's invasion of Belgium and Holland. Eben Emael garrisoned 800 men; was encircled by a moat; and had tank barricades, expanses of barded wire, machine gun nests, minefields and heavy artillery. However the roof of this heavily camouflaged fort was a meadow-like expanse 1,000 yards long and 800 yards wide. A perfect place for a glider to land. The German gliders were towed by Junkers 52s, three-engine transports, from an airfield near Cologne. Their pilots circled to an altitude of 8,500 feet, and then flew a 45-mile course paralleling the German front lines. When the objective, 20 miles behind the Belgian border, was easily within reach, the glider pilots released. Twenty minutes after landing on top of Eben Emael, the Germans had sealed the garrison inside the fort at a cost to them of six dead and 20 wounded. Besides the gliders, a key to the success of this daring mission was a top-secret, hollow-charge device which when detonated, imploded. That is, the charge blew inward, not up and out. These 100-pound explosives were placed against the steel-reinforced, concrete cupolas and turrets housing observation posts and large-caliber cannon. The tremendous blasts, each accompanied by a miniature mushroom cloud, instantly neutralized weapons and men, even those directly down in the bowels of the fort, with an inverted, volcanic shower of molten metal and concrete shrapnel. The German armies arrived at Eben Emael the next morning, and by that afternoon the fort had been surrendered. Subsequently, Hitler used his combat gliders in Greece on April 26, 1941, and in Crete on May 20 of the same year. The Germans won the eight-day battle for Crete with the use of 13,000 glider infantry and paratroopers, but suffered over 5,000 casualties. Hitler never again used paradrops or gliders on such a massive scale. So how does a combat glider fly ? Four basic forces are at work on a powered aircraft in flight; thrust , drag, lift and gravity. Thrust opposes drag and moves the aircraft forward through the air. It is provided by the engine(s). Drag is the natural resistance of air that opposes an aircraft's forward movement. Lift is the force created by airflow over the wings that oppose gravity, the natural force that pulls the aircraft downward. The same forces are at work on a glider. Thrust is created by the towplane. Drag is air resistance. Lift causes the glider to move forward against gravity. However, once the glider pilot cuts loose from the towplane, the glider was nosed down, with gravity providing the necessary thrust. (In a sailplane, he same forces apply. Even if soaring higher and higher on a thermal or rising air current, the nose of the sailplane must always be pointed down at the proper angle to maintain airspeed - to maintain the proper flow of air over the wings for lift.)

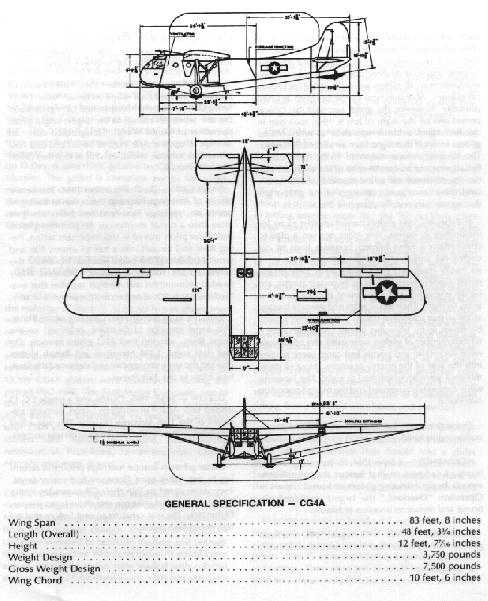

British 30-place Airspeed Horsa Taking a page from Hitler's book, America and Britain developed their own combat glider programs. The American 15-place, Waco CG-4A and British 30-place, Airspeed Horsa gliders were first used in a major invasion (Operation Husky) on July 9, 1943 - he start of the 38-day battle for Sicily. Other major operations where Allied gliders played a significant role were: Operation Thursday (Burma: March 1944); Operation Overlord (Normandy: June 1944); Operation Dragoon (Southern France: August 1944); Operation Market-Garden (Holland: September 1944); Operation Repulse (Bastogne: December 1944 - January 1945); and, on March 24, 1945, Operation Varsity (Rhine River Crossing). Six weeks after the successful conclusion of Varsity, Nazi Germany surrendered to the Allies. Operation Varsity was more costly to Allied airborne than the invasion of Normandy. By early evening of March 24, in eight short hours, our airborne forces had suffered 819 killed, 1,794 wounded and 580 missing in action. Over six dozen paradrop and glider-towing planes were shot down. Seventy glider pilots were killed and 114 wounded or injured. British and American glider-recovery teams found later that less than 25 percent of the gliders landed unscathed. About 6,000 American glider pilots were trained. Almost 14,000 CG-4A's were built; about 3,600 were used in combat overseas. Glider-rider and glider-pilot casualties were estimated at 40 percent for some missions. Specially trained glider-assault regiments were part of the U.S. 11th, 13th, 17th, 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions. (British glider-assault teams were assigned to Air Landing Brigades, each equivalent in strength to a U.S. regiment.) The 11th Airborne spearheaded Operation Gypsy Task Force, a glider-paradrop attack on Japanese installations on Luzon, the Philippines. In the China-Burma-India Theater were glider units-assigned to the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Air Commando Groups - which flew British troops into battle behind the Japanese lines. With a wingspan o 84 feet and 48 feet long, the CG-4A had much in common with the German DFS230: steel tubing framework covered with doped fabric; extensive use of stressed plywood in the wings; and spoilers on the upper wing surfaces. Commanded by a single pilot, the DFS230 landed on a single skid centered beneath the fuselage. The CG-4A was equipped with wheels and hydraulic brakes. The pilots sat side by side. The CG-4A could carry its own weight of 3,750 pounds which usually translated in a cargo combination of men and munitions or high-octane fuel, an artillery piece, or a jeep or baby bulldozer. The same cargo mix applied to the all-wood British Horsa, with a wingspan of 88 feet and a fuselage 68 feet long- and a tricycle landing gear. Its net weight was 8,400 pounds; gross weight was 15,,750. Unlike the CG-4A, the Horsa was instrumented for blind flying, and had two enormous flaps which worked off two interconnected, compressed-air cylinders - as did the brakes. Pilots sat side by side. The CG-4A was towed behind the C-47, the military version of the DC-3, with a nylon tow rope eleven-sixteenths of an inch in diameter, and 350 feet long with a single glider on tow. On a double tow, the tow ropes were 350 and 425 feet long; both attached to a D-ring coupler that fitted to the towplane's tail. The gliders were positioned about 75 feet apart. The Horsa was towed, with a hemp rope, behind the modified, four-engine Handley-Page Halifax bomber, the twin-engine Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle and the C-47.

WRIGHT-PATTERSON AIR FORCE BASE, Ohio (AFNS) -- In Caen, France, there is a museum dedicated to aircraft used in World War II by the Allied forces. Among those featured are gliders, the most famous of which -- the CG-4A Waco -- was developed here at Wright Field, manufactured by the Waco Aircraft Co. in nearby Troy, Ohio, and used successfully by the Allies to invade France and cross the Rhine River into Germany. Allied troops preferred the CG-4A because it was considerably stronger than other gliders, due to its metal frame; others would crumble like cardboard boxes if anything were in the way upon landing. And in a glider, troops had only one chance to land correctly. How did Wright Field come to play an important role in glider history? With the Wright brothers' first, power-driven airplane developed in 1903, gliders might have been forced into history books as a thing of the past, but they made a huge comeback in the years that encompassed World War I -- as well as World War II. Despite newer technology, gliders were revived by Germany in the 1920s as a tactical necessity because the Treaty of Versailles, which concluded World War I, restricted airplane production and utilization. Later, Germany successfully used gliders in invasions, as in 1939 when gliders carried troops and cargo for the invasion of Poland. Herman Goering, World War I pilot ace and leader of the Luftwaffe in World War II, said, "Our whole future is in the air. And it is by airpower that we are going to recapture the German Empire. To accomplish this, we will do three things. First, we will teach gliding as a sport to all our young men. Then we will build up commercial aviation. Finally, we will create the skeleton of a military air force. When the time comes we will put all three together--and the German Empire will be reborn." American government officials reasoned that with powered aircraft, there was little need for the glider. And as late as 1938 the War Department did not encourage a glider program because it could not conceive of the glider as a military weapon. By 1940-41, the Germans were using gliders in many tactical missions to include the widely lauded invasion of Crete. In fact, Germany's successful military use of gliders proved to the American government that the concept of tactical gliders was worthy of exploration. Thus, the War Department commissioned the American Glider Program headed by Lewin B. Barringer (later Major) until 1943 when his plane disappeared over the Caribbean. The program then moved to Headquarters, Army Air Force Office of the Special Assistant on the Army Air Force's Glider Program, under the direction of Richard C. DuPont. A second tragedy plagued the glider program when DuPont was killed in a glider crash five months after his appointment. Yet, the mission would not die; his brother Maj. Felix DuPont was appointed to succeed him and directed the program from the Engineering Division at Wright-Patterson. Relocated twice, before moving to Wright Field, the program became a function of the Aircraft Laboratory Engineering Division at Wright Field in the early 1940s. Then one of the largest aviation research and development centers in the world during World War II, Wright Field tested gliders of many types under the War Department's American Glider Program. By 1945, the Army Air Corps had developed and tested almost every type of tactical glider to include assault gliders, powered gliders, tow planes and cargo-carrying gliders, including ones from the Waco Aircraft Co. American's faith in gliders became evident when the Air Corps placed an order for the procurement of 18,000 gliders varying in model configuration and purpose and ranging in price from $14,000 to $32,000 a glider. Of those, the Waco is most famous for its impact in the D-Day invasion when it carried thousands of nurses, troops, and equipment onto enemy fields, contributing most significantly to the defeat of Hitler's Army and to America's victory in World War II. Today there is a CG-4A on display in the U.S. Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. The Atterbury-Bakalar Museum in Columbus, Indiana is currently restoring the cockpit area of a CG-4A glider. It is planned to be ready in time for the museum's planned expansion in 1999 and visitors will be able to climb inside the cockpit and experience the Pilot's and Co-Pilot's view. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|