|

THE GERMAN PRISONER OF WAR CAMP AT

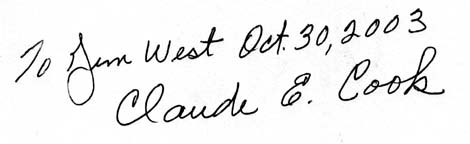

AUSTIN, INDIANA Claude E. Cook

|

| SOURCES: NATIONAL ARCHIVES: Record Group 59, State Department, Decimal file 711.6214 Incidents involving German PWs September-November 1944, boxes 2203, 2204. Record Group 389, Office of the Provost Marshal General, Prisoner of War Division: POW Division History, box 34. Camp Atterbury, Indiana, box 2654. Labor Reports, Austin Branch Camp, Austin, Indiana, 1944-46. INDIANA STATE LIBRARY, INDIANA DIVISION: Dorothy Riker: The Hoosier Training Ground.- A History of Army and Navy Training Centers, Camps, Forts, Depots, and other Military Installations Within the State Boundaries during WW2, (Bloomington, IN, 1952) Randall Lee Roller, "The Atterbury Prisoner of War Camp." Indiana Military History Journal, vol. 4, no. T (1979). CAMP CRIER, January 1944-June 1946: (Camp Atterbury newspaper.) INDIANA STATE LIBRARY, NEWSPAPER DIVISION: (John Selch) Columbus, Edinburgh, Franklin, and Scottsburg newspapers, 1944-1946. AUSTIN PUBLIC LIBRARY, AUSTIN, INDIANA Scott County-Celebrating 975 years-A Pictorial History. Turner Publishing, 1995 BALL STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, MUNCIE, INDIANA: Edward D. Pluth, Administration and Operation of German Prisoner of War Camps in the United States during WW 19. (Thesis, Ball State University.) Oral interviews: Nelson Hedrick, Jackie Lee Hedrick, Hugh Green, Mildred Smith. |

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS |

| PREFACE Due to the critical labor shortage existing when the 1944 canning season arrived, several packing plants applied to use prisoners of war being held at Camp Atterbury, IN. Consequently, the army established a branch prisoner of war camp at Morgan Packing Company in Austin, Indiana. One of those applying to the War Manpower Commission for a labor contract was Rider Packing Company in the small town of Campbellsburg, Washington County. This, plus a lack of information regarding the Austin camp, led to the writing of this history. The 1929 Geneva Convention prohibited prisoners of war from doing work degrading, dangerous, unhealthy, or work they were not physically able to do. Other prohibitions included working on projects connected with military operations and working longer hours than civilians engaged in similar work. Work days, including travel time, could be no longer than ten hours except in an emergency. In no event were they to work more than nine consecutive days without a day of rest. Rest days, usually given on Sundays, were to consist of 24 consecutive hours. Although not required to work, non-commissioned enlisted men and officers often volunteered to do so. Prisoners received an allowance of 10 cents daily to purchase such items as tobacco, toothpaste, shoe polish, and razor blades at the camp canteen or PX. They also received 80 cents daily in canteen coupons when engaged in work not benefiting themselves. The local office of the War Manpower Commission received all requests for prisoner of war labor. If approved, the WMC issued a certification of need stating that a need existed for such labor and that no civilians were available to do it. The request then went to the Camp Atterbury contract officer who drew up an agreement between the government and the plant. The agreement specified the work location, contract number, length of contract, the beginning date, and the cost. The plant agreed to pay each PW the prevailing local wage; however, PWs kept only the daily 80 cent allowance deducted from their wages. The balance went to the US Treasury to support the PW program. Contractors agreed to furnish working conditions equal to those furnished local workers and to provide transportation between the PW camp and the job. They also agreed to furnish toilets, a clean work place, all needed equipment, and to pay for any rations provided. Each employer prepared a letter containing the following information; the name, serial number, nationality of each PW, number of hours worked, daily rate of pay, and amount due each PW. The Commanding Officer of Camp Atterbury received the original letter, certified as true and correct, four copies of the letter, and a certified check payable to the US Treasury. Activated December 15, 1942, the 45 acre PW camp at Camp Atterbury was on the western edge of the reservation. Colonel John Gammell served as the only commanding officer. When activated, the 1537th Service Unit operated the camp. On April 13, 1944 the camp reorganized. At that time the 429th and 577th Military Police Escort guard Companies, responsible for guarding PWs, became part of the 1537 Service Unit. After reorganizing, the only two components of the 1537th were a Headquarters Detachment and a Guard Detachment. Captain Robert L. Tate became the commanding officer of the Guard Detachment and Captain George P. Wacker became the commanding officer of the prisoner of war stockade. The 1537 Service Unit became 1560th Service Command Unit on February 1, 1945 in compliance with orders establishing service units in a uniform way.. |

| The first PWs, Italians, arrived April 30,

1943. Germans replaced the Italians on May 8,1944, remaining until the

deactivation of Camp Atterbury on June 27, 1946. The camp contained three

compounds, each with a capacity of 1,000 prisoners. However, due to the

large number working nights, it later became possible to house more than

3,000. On August 24, 1944 the camp held 2,107 privates, 856 non-coms, and

23 sanitary personnel for a total of 2,966 prisoners. (Sanitary personnel

were chaplains and medical officers.) On September 10, 1945 the number

held at Camp Atterbury (3,851) and branch camps totaled 7,648. Included

were 1200 officers, 99 non-commissioned officers, and 6,347 enlisted men. A September 10, 1945 report noted Camp Atterbury PW camp operations required only 330 US Army enlisted men. An additional 269 men at five branch camps raised the total to only 599. Camp Atterbury became recognized as one of the better PW camps in the US even though it operated with a minimum of personnel. Most prisoners worked every day except Sunday, either on post or on contract work. In August 1944 the number assigned to camp details totaled 2,300. An additional 1,700 worked off post in glass or fertilizer factories, and fruit and vegetable canneries. In April 1944 planning began for constructing PW branch camps. Designed to fill a definite work need, the branch camps were either permanent or temporary. PW labor assisted in the construction of the camps as much as possible. Although they had their own administrative staffs, they remained under the overall command of their base camp. Little concerning them appeared in newspapers because the army felt the presence of PWs alarmed area residents. The War Department considered camp locations, as well as the number of PWs in each camp, a military secret. The Camp Atterbury prisoner of war camp served as base camp for five of the seven branch camps known to exist in Indiana during WW2. The five were at Austin, Windfall, Vincennes, Morristown, and Eaton. Other sources state all the Camp Atterbury branch camps remained open during the winter of 1944. However, official reports of December 1,1944, February 1, 1945, and May 1, 1945 make it clear the only camp open on those dates was the one at Austin. In August 1944 the army activated the branch camps at Austin, Windfall, Vincennes, and Morristown under the overall command of Captain Robert L. Tate. The first press release from Camp Atterbury, dated September 6, 1944, reported German PWs were giving valuable aid to farmers and packers by working in branch camps. An October 20, 1944 press release noted the number of details sent out as 320, the number of men in the details ranged from 1 to 50, and the average daily wage was around $4.00. On April 24, 1945 the War Manpower Commission indicated it needed 6,350 PWs for the 1945 canning season. The War Food Administration indicated it needed another 3,250. Plans included distributing the prisoners among Camp Atterbury and seven branch camps. Of three new branch camps contemplated at the time, however, only the one at Eaton emerged. The two branch camps in Indiana not administered by Camp Atterbury were at Fort Wayne and Jeffersonville. One at Camp Thomas Scott, Fort Wayne, activated November 1, 1944, operated under the command of Camp Perry, Ohio. A branch camp at the Jeffersonville Quartermaster Depot opened in January 1945 under the command of Fort Knox, Kentucky. Prisoners there also worked on construction projects at the Indiana Ordinance Works, Charlestown. |

| PART 1: THE AUSTIN BRANCH CAMP. The Austin branch camp, 50 miles south of Camp Atterbury, was one of four temporary camps established in August 1944. Although always maintained as a temporary camp, the Army gave serious consideration to making it permanent until the spring of 1945 when the war in Europe began winding down. The temporary classification resulted in the prisoners living in tents. Camp capacity ranged from 900 when established to 1500 or more by the time it closed in April 1946. Officers from Camp Atterbury met with local officials and members of the press to provide the area with advance publicity before the camp opened. The first public announcement concerning it appeared in the August 24, 1944 Scott County Journal, The paper reported the arrival of an estimated 350 German prisoners at Austin and that a fenced area in the rear of the Morgan Packing Company plant served as their quarters. It added that "most likely" groups of ten or more guarded PWs would work in the warehouse, but gave no more details. The camp eventually grew to include most of the area behind the Morgan plant between the Pennsylvania Railroad and Christie Road. Detachment #1, 1537th Service Unit operated the Austin camp upon its activation August 18, 1944. The first camp commander was Captain Fred M. Waggoner, CMP: Captain Arlie G. Belcher, CMP, became commander November 1, 1944, remaining until the camp closed. The 1537th Service Unit was redesignated the 1560th Service Command Unit on February 1, 1945. Captain Belcher and Major Ray Kessel, a physician, were the camp administrators on May 1, 1945. Duty assignments September 8, 1945 were as follows: Commanding Officer: Captain Arlie G. Belcher; Supply Officer, 1st Lt. Frank Russell, INF.; PW Company Commander: Lt. Alden B. Mellick, FA. Only about 45 US enlisted men were necessary at first, but this number later increased in proportion to the number of prisoners held. On September 8, 1945 70 US Army enlisted men were at Austin. Because the prisoners slept in tents, the Geneva Convention required the guards to do likewise. Two chain link fences, 10 feet high, made of hog wire, with a barbed wire overhang enclosed PW camps. Guard towers, armed with machine guns, were on all four corners and within the 8 foot alley between fences. Flood lights, search lights, as well at auxiliary lighting systems were also standard. Buildings and tents were at least thirty feet from the fences. The only known escapees from Austin were Max Winded and Max Bauer. Both men were missing during a late check on September 19, 1944. Described as segregated anti-Nazis, both had on blue denim uniforms with large white PWs lettered on the back. Percy Wily, Agent in Charge of the FBI at Indianapolis, announced the escape the next day. His office also bore the responsibility of coordinating the search. Their description follows: Federal, state, and Scott County authorities joined in the search. On September 21 hunger forced the escapees to a farmhouse near Austin where Military Police from Camp Atterbury apprehended them. The usual punishment for escaping was confinement on bread and water for up to 14 days. Perhaps all security systems were not in place at this time. (No record of the escape survives in Camp Atterbury or FBI files at the National Archives.) Page 11 |

| The first PWs sent to Austin found

conditions much worse than those at Camp Atterbury, a situation that

continued until at least January 1945. During the war the Swiss Legation

acted as protective power for German interests in this country. When Emil

Greuter and Curt Ritter, of the Legation, inspected the camp on December

1, 1944 they declared it to be one of the most primitive prisoner of war

camps ever visited by them. At that time the camp held 880 regularly

assigned PWs, all employed at Morgan's Austin plant. An additional 300

came from Camp Atterbury by truck daily, except Sunday, to work at the

plant. Greuter and Ritter noted that not all PWs were in winterized tents

although winter had arrived with snow and ice on the ground. Those not in

winterized tents built stoves and stove pipes out of old tin cans to get a

little heat. This created a serious fire hazard as the tents were very

close together. The camp commander promised the Swiss inspectors to

complete the winterizing of all tents over the week-end, but failed to do

so. The latrines, as well as washing and bathing facilities, were "quite

primitive," but were being improved. Captain Belcher reported that

completion of a canteen and mess hall under construction was only a few

days away. (This also would turn out to be false, at least in regard to

the mess hall.) For the time being prisoners were eating in their tents

from mess kits. PW morale remained high despite undesirable living

conditions. The reported bayoneting of some prisoners at Austin in September, plus the failure of a protest letter regarding the incident to reach the Swiss Legation, disturbed the inspectors. They traveled to Camp Breckenridge, KY to interview the former PW representative at Camp Atterbury regarding the complaint. A discussion of the matter with Colonel Gammell at the main camp resulted in Gammell stating he would look into the matter, try to locate the letter if possible, and send it to the legation. The inspectors hoped this would occur as soon as possible. Noting that a question of violating the Geneva treaty existed, they felt it might be helpful to include some explanation of the delay. (State Department records concerning prisoners of war through November 1944 contain no mention of this reported incident.) The report also stated that the delay in winterizing the camp and other improvements was unfortunate as it prevented the camp from making at least a satisfactory impression. As a result, they rated the camp as not up to the usual American standards. There were other problems as well. In late December 1944 the 5th Service Command received an intelligence report regarding the Scott County Sheriff. Refusing to be quoted, the sheriff said that considerable feeling existed in Scottsburg that Morgan was using PW labor at considerably less cost than civilian labor. This was because he did not pay overtime for their services. During an interview at the plant, Jack Morgan, son of the owner, said he did not oppose paying overtime on an equitable number of PWs employed by him. He also reported he paid 4,000 civilian employees overtime even during the exempt period allowed by the War Labor Board. A method of computing overtime to cover the 6th day of labor put the pay of PWs on the same basis as civilian employees and solved the problem. Other reports to the service command concerned the PWs being fed in the company cafeteria and being allowed considerable freedom in the cannery. The latter turned out to be true as an inspection by service command officers noted very few guards within the plant. Morgan reported sabotage on some boxes of canned goods for the Army, such as puncturing cans to allow catsup to flow out, making it necessary to replace spoiled cartons. The report also noted that local civilians, as well as US soldiers from the branch camp, had written Walter Winchell requesting the matter be put on the radio. The service command termed the reports "unfounded and nebulous," but stated they were watching the situation. Page 2 |

| A memo of January 5, 1945 noted Morgan was

furnishing lumber to winterize the tents as the government had not done

so, probably due to the scarcity of lumber. Morgan, who was also supplying

enough lumber to construct a theater, was anxious that nothing disturb the

good relations between himself and the base camp. He wanted 1000 more

prisoners and was buying land to set up additional tents. He also reported

the PWs were good workers and that he could not get sufficient civilian

labor during the packing season. At this time there were 800 prisoners at

Austin. An additional 200 traveled back and forth daily, except Sunday,

from Camp Atterbury to work at the plant. A public perception that PWs in the US received coddled treatment prompted a letter from Army Service Forces to PW camp commanders April 24, 1945. It recommended taking the following steps in order to avoid possible public criticism:

|

| A newly constructed 460 seat theater

presented weekly movies and served as a place for PWs to present their own

theatricals every other week. The recently formed 22 piece PW orchestra,

described as "much better than average," also performed there. A small

recreation field served as a place to play soccer, handball and volleyball

games. Construction was also underway on a tennis court. Morgan also built a 300 foot by 120 foot day room for the use of the PWs. There was also a very well organized library that included books, some in English, donated by the German Red Cross and the YMCA. Evening courses on general education, languages, stenography, mechanics, agriculture and mathematics were available there. Classes in US History, US Government, and American life style began in early 1945. Known as the intellectual diversion program, they were an attempt to politically reorient the prisoners. (The program met with some success. A number of converts returned home and helped form a democratic West Germany.) The YMCA furnished phonograph records and there was a sufficient number of games and jumping equipment. Catholic and Protestant religious services both took place Sundays at altars built by the prisoners. Sanitary arrangements were very primitive. A plan, monitored daily, called for the flushing of toilets with running water three times each day. The health of the PWs was excellent. The only complaint during the visit was the removal, and non-replacement, of a few wash basins. Captain Belcher ordered their replacement at once, adding it was just an oversight on his part. Morgan termed the work by the PWs as very satisfactory and said he was not aware of any misconduct between them and his employees. The inspectors called attention to the fact that over the past six months PW work resulted in income of $378,093.89. PW allowance and pay came to $94,866.40, leaving a profit to the government of $283,277.49. A September 6, 1945 camp labor report shows 143 non-commissioned officers and 1457 privates, a total of 1500 PWs. Of these, 98 were unable to work; 34 due to temporary medical reasons, and 14 were physically unable to work. The rest were all working at jobs assigned to them. The report, including 13 rest days, shows the following 1389 man days by projects: PW Camp Overhead: 25 unpaid company and stockade; 61 paid company and stockade; 6 PW canteen; 0 officer orderlies or cooks; 5 PW Medical and 2 PW camp fund for a total of 99 man days. 5th Service Command activities at Austin branch camp: 62 man days. Contract work for food processing: 1228 man days. An officer from the Office of the Provost Marshal General inspected the camp September 10, 1945. His report included the following notes:

|

| certified by the WMC, effective September

1, called for 50 cents per hour, plus overtime. It was held in abeyance;

however, pending receipt of WLB General order #30 as it apparently would

permit the contract to be entered into for 40 cents per hour. When inspecting officers visited Morgan's Austin plant September 6, 1945 they found approximately 25 PWs engaged in new construction, laying glazed interior and rough exterior brick, and building scaffolding. About 40 other PWs were mixing concrete, paving driveways, and paving parking areas. During a visit to the WMC Indianapolis office the

officers learned certification of need for common labor at food processing

plants did not cover skilled labor. At 1130, September 8th, they informed

Jack Morgan to quit using PWs for skilled labor at once, unless so

certified by WMC. Inquiry revealed this work had been going on for the

past three weeks. PW labor also built ten houses, two each of five

different designs, on Broadway Street in Austin during this period. |

| PART 2: THE CAMPBELLSBURG CONNECTION.. In the fall of 1944 a small group of German prisoners of war being held at Austin arrived in Campbellsburg to work at Rider Packing Company. This was probably the most unexpected event on the local home front during WW2. Unfortunately, the National Archives has no information regarding specific contracts for the 1944 canning season. Although there were five copies of each contract, none regarding the one with Rider apparently exists today. Evidently, either the government destroyed them or they burned during fires at the Rider factory and home. Therefore, the recollections of local residents and known War Department policy provides most of the information for this section. The 1944 tomato crop arrived two weeks later than usual due to a wet spring that delayed planting, and a hot dry July that prevented ripening at the usual time. As usual, the canning season began when enough tomatoes were on hand to run three or four hours a day on two or three days a week. The first 1944 run was from 9 AM until 12 noon, Saturday, August 19th with the next run scheduled August 23rd. There was, of course, a great shortage of workers that fall. Even before the canning season began a request went out for anyone who could be of any help at all to register at the factory. Although several showed up to work the first day, a plea went out for anyone eligible to show up on working days. About the first of September the factory began a six day work week, including some days of ten hours or more. From all indications the work continued, mostly full time, until the end of the first week of October. Postponing the opening of school from September o ;Lo September 15 allowed the older boys extra time to help at the factory. However, due to the shortage of workers, the Riders decided to apply to use the prisoner of war labor made available by the government. Based on the above dates, the PWs probably worked here for four or five weeks beginning about the first of September when a full eight hour work day became available. They no longer came after the work slowed to less than eight hours a day. Standard practice, when possible, assigned she same PWs and the same guards to work details. This was true at Riders. Prisoners probably left Austin at 7 AM, the usual departing time for the first shift. They traveled to Campbellsburg and back in an enclosed delivery type van owned by Rider and built by Rider employee Charley Free. The van, placed on a 1940 International truck chassis, was about 26 feet long. Double doors in the rear provided the only exit or entrance. Prisoners sat on removable benches arranged along both sides of the van interior and the guard sat in the rear. No one recalls the name of the Rider employee who drove the van. Although the standard ratio was 1 guard for 10 PWs, this was seldom the case due to the chronic shortage of guards. This was particularly true for prisoners considered anti-Nazis. Jack Hedrick, allowed to count the prisoners by the guard at times, believes there were 12 in the group. Others think there were more than that. Army records indicate the usual work detail assigned to small canning factories at this time consisted of 15 PWs and 1 guard. The regular guard, whose name no one now recalls, was a short heavy set Staff Sergeant who carried a .30 caliber carbine. Usually, the carbine sat in the corner all day. This was not as dangerous or careless as it seems as guards commonly carried an unloaded gun, a fact well known to the prisoners. However, guards carried a full clip of ammunition in one pocket, another fact well known to the prisoners. The fact that a Staff Sergeant was on regular guard detail points out the severe shortage of available guards. A substitute guard, used when the regular guard was off duty for any reason, carried a .45 caliber pistol. Page 6 |

| Rules prohibited PWs from working with, or

near, women. Therefore, they usually worked in the warehouse where, under

the supervision of Nelson Hedrick, they usually stacked cans. One helped

in the area where Harve Nicholson and Verle Smith cooked canned tomatoes

in large vats. They also possibly helped run the labeling machine and

loaded cartons of canned tomatoes into box cars. (These last two jobs,

usually done after the canning ended, possibly were done at this time

because the government was buying 25 percent of the tomato crop for

service men.) When needed, they unloaded hampers of tomatoes arriving at the plant by truck. At times, they also dumped tomatoes into a scalding machine under the supervision of "Tump" McNeely. Most were good workers who carried out assigned tasks efficiently. They wore the standard blue denim PW uniform and worked an eight hour day while here. At the noon break PWs ate lunches packaged at Austin. They also had two ten minute breaks ("pauses" to them) during a day. Many wore rings made at Camp Kilmer, NJ, their US port of arrival. All were fairly young; most were probably in their early 20's. The fact that they were "so blonde" made an impression on local residents. Some bore scars from wounds suffered previously. Evidently ail were privates in grade. Although most caused no trouble while here, one among the first arrivals caused Mr. Rider considerable consternation by claiming friendship with Adolph Hitler. He also claimed he ate Christmas dinner with Hitler in 1943. While he was in the group the guard carried a Tommy gun instead of a carbine. After a few days, Rider told them not to bring the trouble making prisoner anymore. (Without a doubt, a close friend of Hitler would have been an officer, not an enlisted man. There were no PW officers at Austin at this time.) Perhaps the story became distorted over the years and refers to Max Bauer; the only known prisoner removed from the original detail. However, the reason for his removal was his escape from the Austin camp, not a friendship with Hitler. Hans Sauer, who was Hitler's personal pilot for many years, was also his close friend. Although Hans auer probably attended Hitler's 1943 Christmas dinner, Max Bauer spent that day in a PW camp. Any connection between the two remains unknown. The presence of the prisoners brought mixed reactions from the local population. Some older residents, especially those with sons in the service, thought Rider had no business bringing them to the town. Others worried about escapees causing trouble. However, most factory workers treated them well. One woman, having two sons in the service, brought them pie. When asked why, she replied she wanted her sons treated well if captured by the Germans. Another drew criticism for bringing them cookies. One woman reportedly became so fond of one that she expressed hopes of going to Germany after the war. Given the limited contact between the females and PWs, however, this seems extremely doubtful. One of the residents feeling no good will toward them was Ross Hayes, the local feed store owner who frequently visited the factory to show his disdain for them. A favorite pastime of his was raising their ire by showing daily newspaper headlines about how badly the war was going for them. "Our buzz bombs will show you that it is not over yet;" replied one angry PW. Although others reported the PWs did not wander around, Hugh Green, a soldier home on furlough, heard German being spoken outside his home near the Washington Street railroad crossing. Going outside to investigate, he witnessed three or four unguarded PWs walking along the railroad toward the factory. They had apparently been to town unguarded. Green reported the incident to the Seymour State Police post and noticed no other occurrences. Government policy made many such incidents possible. Early 1944 official policy, known as the "Calculated Risk" policy, called for using only the number of guards required to maintain a reasonable amount of security. Designed to use a minimum number of guards, the policy became necessary due to the increased use of PW labor and the large number of Page 7 |

| guards overseas. Not expecting complete

security, the army realized a few escapes would occur. The policy led to

occasional citizen protests regarding what they perceived as a laxity in

guarding PWs. Although no list containing the names of these prisoners exists today, Nelson Hedrick recalled the following names and information fifty-two years later. 1. Ewald Schmidt, regular interpreter, spoke good English, from Duisburg in Westphalia. 2. (first name unknown) Klemmer, spoke some English, acted as interpreter if needed. 3. Emil Kinder, the group comedian, and probably the PW recalled as giving the Nazi salute and crying "Heil Hitlerl" when a large stack of cans collapsed. 4. Karl Schultsnester, anti-Nazi from Berlin, business closed by the Gestapo. He had not heard from wife and family for a long time and did not know what had happened to them. He looked a lot like band leader Harry James and was possibly in the Luftwaffe. 5. Hans Eble, a former cabaret singer from Westphalia. Brought candy bars to the Rider girls and sang to them. At work, he often sang "Lill Marlene," a German song popular among troops of all nations. He said he learned the English version by watching a Betty Grable movie. He wrote to Frances Rider for several years after the war. 6. Max Bauer, age 18, in the group until escaping from Austin on September 19, 1944. He never returned after being recaptured. Possibly from East Prussia, Bauer died in Germany in August 1993 according to WASt Record Center in Berlin. 7. Kord Burfiend. Nothing else recalled. 8. Klaus Burfiend, a brother of Kord, nothing else recalled. One, a gymnast from East Prussia, was able to grab the rungs on the side of a box car, then raise and hold his body out horizontally. Some could speak a little English, such as "Good Morning" and "How are you?" Most had a hard time trying to translate American song titles, however. Possessing money of any kind by a prisoner violated regulations. However, one somehow managed to get a dime. Giving it to young Jackie Hedrick, he requested him to bring him a pack of cigarettes. Needing more money, Jack stopped at home to borrow the other six cents needed to buy a pack of Marvels at that time. Unfortunately for him, the guard caught him giving the PW the cigarettes and gave him a good bawling out. Attempts to locate, or get additional information, regarding these former prisoners was not successful. The German Consulate at Detroit, MI furnished addresses for Verband Deutscher Soldaten, em. and Verband Deutsches Afrika-Korps. Verband Deutscher Soldaten printed my request for information in their April 1996 issue of Soldat in Volk. Verband Deutsches AfricaKorps printed the same request in the May 1996 issue of their publication Die Oase. As a result of the query in Die Oase, I received a letter in June 1996 from Gerhard Hennecke, Grafschaft, Hauptstrasse 23, 57392 Schmallenberg, Germany. Hennecke, captured in North Africa in 1943, spent from 1944 until 1946 as a PW at Camp Atterbury and Austin. He wrote that he did not know any of the PWs assigned to Rider, but was interested in locating two civilian friends he met while at Camp Atterbury. A reply from the WASt Record Center, Eichborndamm 179, Berlin, Germany received on February 26, 1996 supplied the fact that Max Bauer died in August 1993. It also stated that full names, along with date and place of birth, were necessary before a record search for the others was possible. THE END Page 8 |

Page last revised

09/03/2022 Page last revised

09/03/2022James D. West www.IndianaMilitary.org Host106th@106thInfDivAssn.org |