The Falcons Of Freeman Field

Testing Japan's Eleventh Hour Entrants

by Jack Dean

Photo at Freeman Field

Editor's Note:

Located in the fertile farmland of Indiana, Freeman Field became the Air

Force's special testing ground for captured enemy aircraft. To be sure,

other facilities, both at home and overseas, also evaluated captured enemy

equipment. In the case of Japanese planes, the first was at San Diego. A

short time later, testing was removed to Anacostia Naval Air Station, near

Washington, D.C. But as more and more Japanese aircraft were brought back

from preliminary tests, usually performed in Australia, Freeman Field was

expanded to handle the rapidly increasing influx, many of which were new

and exotic to technical intelligence officers and mechanics who had been

led to believe that every other Japanese aircraft was either a Zero

fighter or a clumsy, heavily spatted bomber. By the end of WW II, every

Japanese and German type had passed through Freeman Field, and for as long

as two years after the close of WW II, these aircraft were still being

evaluated, tabulated and chronicled.

In fact, so many enemy types were in

the air, that had they not known better, former service pilots would have

sworn that the Japanese were again attacking the U.S. Unfortunately, far

too many of them were also destroyed, although a few were stored for later

museum and display purposes. Here then is a survey of what Allied

Technical Intelligence discovered about Japan's late war aerial threat. A

threat that might have very well materialized into a grim reality, were it

not for the development of America's heavy, long range bomber, the B-29.

While the Japanese Navy was having Mitsubishi design a naval interceptor,

the Army, while giving the go-ahead for lull protection of Nakajima's Ki

43 Oscar, a classic dogfighting aircraft, also had that same company come

up with their concept of an interceptor for defense against bombers. The

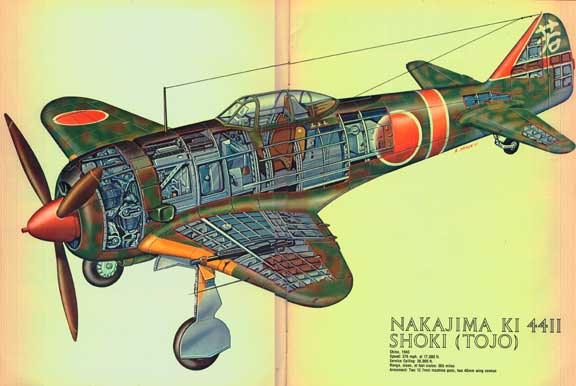

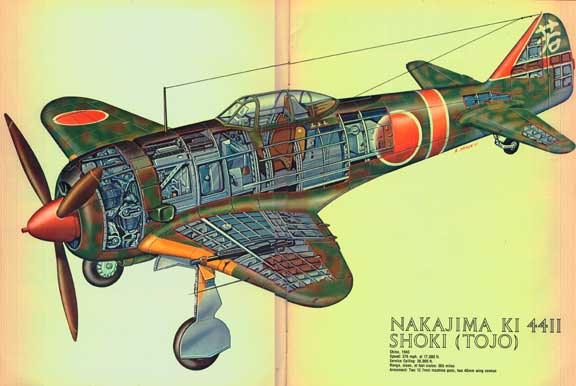

result was the Ki 44 Shoki (Demon) codenamed Tojo. A typical Nakajima

product, but with maneuverability sacrificed for climb and speed, its

fuselage was altered to accommodate a brutish engine which, in the last Ki

44-III model, had an output of 2000 hp. for take off. Bomber busting was

the task of this pugnacious-looking bird and its 40mm cannon, one of which

is shown projecting from the right wind leading edge, was tailormade for

the job.

When Japan entered WW II against the United States, her Air Forces

possessed the best naval fighter in being, the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, the

best torpedo bomber, the Nakajima B5N2 Kate, a solid, long ranging twin

engined naval bomber, the Mitsubishi G4M2 Betty, and a host of

satisfactory auxiliary naval types, but Japan's Imperial Army Air Force,

was not so advanced. Its most numerous fighter, the Ki-43 Oscar, while one

of the most maneuverable aircraft ever conceived, suffered from lack of

speed, lack of armament and a near total lack of pilot protection. Despite

considerable revamping throughout the war, these problems were never fully

solved and Japan was forced to rely on newer replacement types then on the

drawing boards or under construction.

Unfortunately for the

Japanese war planners, while they had shown the foresight to undertake the

design and construction of improved replacements, they had overlooked the

possibility that these replacement aircraft would have to be built under

other than ideal conditions. Raw materials, gasoline and other vital

ingredients so crucial to running a successful aviation industry, quickly

became scarce or disappeared altogether. Industries were short of skilled

labor, with many factory assembly lines being manned by women with no

previous training. Then, too, a multiplicity of designs, many of them

deadend and wasteful, added a further strain to Japan's already

overburdened technological resources, and the coup de grace came in 1944,

when her production facilities were burned up from the air in a series of

heavy bombing raids which caused more destruction than the nuclear

bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

With stockpiles of raw materials practically denuded; with her work force

decimated and her major assembly plants a shambles, it was a wonder that

Japan produced any new designs of consequence during the period 1943-45,

but she did, and many of her eleventh hour engines of war were not only

remarkable in their being produced at all, but surpassed, in several

respects, the best the United States — its arsenals safe from attack —

could achieve.

When the U.S. entered the war with Japan late in 1941, our production

facilities were just gearing up for mass delivery. As such, we were forced

to fight the first six months to one year with designs which had been

originated in the mid and late 30s. At the same time, the Japanese were

already operating equipment which had been tested a year or two later.

Although their planes were not as sophisticated and did not provide for

much pilot or crew safety, they performed much better than our own, and

because they outnumbered us in the Pacific, the Japanese Naval and Army

Air Forces ran wild for the first six months. After a period of

indecisiveness, when the balance seesawed first one way, then another, it

became apparent by the beginning of 1943 that Japan's arsenals would be

hard put to match those of the U.S., to say nothing of outstripping her

more powerful enemy. By the end of 1943, it was a foregone conclusion that

Japan would lose the war. The only question was . . . could she conclude a

peace treaty that would leave her home islands intact.

Having lost control of the seas, the Japanese, by 1943, were already

concentrating on production for home defense against aerial attack. To

give their planners credit, the Army had foreseen this possibility and, in

1939, when the Nakajima Ki 43 was accepted for production, Nakajima was

given a contract for an interceptor, the Ki 44, which would trade

maneuverability, the heretofore primary Japanese fighter prerequisite, for

speed and climb. By the end of 1942 the Ki 44 (Tojo) began to reach

Japanese Army Air Force units. Despite the fact that it was restricted in

its aerobatics, particularly at high speeds, service pilots liked its

heavy armament, its rate of climb and diving speed, and if one had to get

very close to insure hitting the target, the Ki 44's 40mm cannon proved

highly successful against heavy American bombers such as the B-29.

In building the Ki 44, Nakajima had, in fact, again altered their basic

fighter design of 1936, the Ki 27 Nate, which, together with the

Mitsubishi A5M Claude, were Japan's first low-wing monoplane fighters.

While the Claude was to be eventually eclipsed by the A6M Zero, a totally

new design, Nakajima was to refine their Nate for nearly a decade,

gradually improving it over the years. If one takes Severky's P-35 fighter

as the first of the line and ends with the Republic P-47N Thunderbolt, by

filling in the intervening changes with the P-43 Lancer, and the P-47B

Razorback, a similar parallel development can be traced in this country.

Within two years of the rather pugnacious-looking Ki 27 Nate's debut, a

slimmer successor, its fuselage silhouette generally drawn out, appeared.

This was Nakajima's Ki 43, Oscar. More powerful and faster, with a cleaner

canopy design, the longer fuselage of the Ki43, still retained the wings

of the Ki 27. With the introduction of the Ki44, in 1942, a still more

powerful engine dictated a thicker fuselage, while speed considerations

changed the shape of the wings, but the Ki 44 retained a distinct

resemblance to the Ki 43. By 1944, yet-another Nakajima fighter arrived on

the scene to once again alter, but not appreciably change, the basic

concept. Resembling a beefed up Ki 43, but without the Ki 44's rotund

fuselage, and featuring wings and tail group very similar to those of the

Ki 43 Oscar, the Ki 84 Gale was, perhaps, the finest Japanese fighter of

WW II. Certainly, it saw the most combat of those types introduced late in

the war. Designed in 1942, debuting in 1944, the Ki 84 was fast enough at

392 mph, possessed of exceptional range, 1,053 miles, heavy armament, two

12.7mm machine guns and a pair of 20mm cannons, afforded protection for

the pilot, was very maneuverable, and for emergencies, was capable of 427

mph for short periods.

Well designed and brilliantly conceived, the career of the Gale notonly

exhibited the competence of native Japanese technology and creative

genius, but also demonstrates how resourceful, even if handicapped,

Japan's wartime industries were by 1944. With aluminum in short supply,

plans to manufacture the Ki 84 from wood were made, the plywood skin to be

heavily lacquered to insure a smooth finish. Other variants were to be

built partly of steel (cockpit sections, ribs, bulk-heads) and partly from

wood, with sheet steel skinning. Although production Gales were plagued by

inferior workmanship, due to the fact that unskilled workers, many of them

teenagers, were putting them together, Nakajima still managed to deliver

3,382 production Ki 84s in only 17 months, a rather amazing accomplishment

when one considers the heavy B-29 raids and the need for the dispersal of

factories through-out the home islands.

Meanwhile, as the Japanese Army was revamping its fighter strength,

switching to interceptors, the Japanese Navy, after being forced to

continue with improved models of the basic Zero, was also looking for a

new fighter. Designed by Jiro Horikoshi's Zero team, the Mitsubishi J2M

Jack, languished on the drawing boards for nearly a year, while its

creators refined the Zero. When introduced in 1942, the Jack, with its

laminar-flow wing, the first on a Japanese aircraft, proved stable and

steep climbing, but engine trouble hampered full scale production and

although it was possibly the best bomber destroyer the Japanese possessed,

it lost nearly two years due to design lag. (See Oct Wings, 1973).

As a result, the hardpressed Japanese Navy turned to Kawanishi to provide

it with an alternative to the Zero. Kawanishi had developed the N1K1

floatplane fighter, codenamed Rex. Extremely advanced, it had been built

in very limited numbers, but Kawanishi had other ideas for their design.

If the A6M Zero could be turned into the A6M-N Rufe float plane fighter by

Mitsubishi, why couldn't the Rex be converted into an orthodox fighter

like the Zero? In December, 1941, Kawanishi presented this proposal and in

only seven months, the new landplane fighter was flown.

Although only 1,400 N1K1-Js were built, codenamed George, due mainly to

landing gear and engine problems, the George was probably the fastest, and

most maneuverable Japanese naval fighter of the war. In the hands of a

veteran pilot it was a formidable adversary, particularly the later models

with four 20mm wing cannon. It possessed good range (1,375 miles) and

although maximum speed was under 370 mph. its handling was sterling.

Because the power of its Homare 21 engine fell off rapidly at high

altitudes, it was of little use against high flying B-29s, but against

F6Fs and F4Us in middle and low altitude dogfights, it was spectacular. In

February 1945, a lone Japanese ace, Warrant Officer Kinsuke Muto, engaged

a dozen F6F Hellcats, single-handed, while flying a George. He destroyed

four and forced the others to break off.

These last minute heroics, however, were the beginning of the end of

Japan's aviation industry. While her newer fighters proved too little and

too late, Japan persisted in building twin-engined fighters such as the Ki

44 Nick, which, despite improvements, still was basically an obsolete

heavy fighter on the order of the German Me 110, one that could not

maneuver with its single-seat counterparts. The naval air program also

continued down the same engineering cul de sac. As the war news became

grimmer, Japan introduced yet another three man torpedo and/or dive

bomber. Also doubling as reconnaissance machines, these newcomers, such as

the Yokosuka D4Y Judy, were generally slower than enemy fighters and, due

to a lack of escorts, suffered heavily, even though they had a top speed

of 350 mph.

They were also assigned to carriers which, by the fall of 1944, had ceased

to exist. Their bomb loads were comparatively light and, when compared to

American successors to the veteran Douglas SBD, such as the BTD-1 and

XSB2D-1, which were abandoned in favor of the single-seat AD Skyraider,

were inferior in every respect. Yet they continued to be produced. Had

they been in service in 1942, the tide of battle in the Pacific might have

been reversed. However, the same could be said of American types like the

P-38, P-51 and Skyraider.

In the final reckoning, Japan's war planners had been correct in their

belief that Japan's technology would be able to keep pace with that of the

leading aircraft manufacturing nations of the world. What they did not

allow for, was the consequence of their combat forces being unable to

maintain control of those raw material producing areas seized during the

first months of the war. Add to this the unrelenting strategic bombing

raids conducted by the U.S. during 1944-1945, which all but totally

destroyed their war-making potential, and you have the real reason why the

best known Japanese combat types were those dating from the time of Pearl

Harbor. Thus, many of the Falcons of Freeman Field were forced to show off

their skills, over the peaceful Indiana countryside, instead of the

Pacific. And judging by their performance, it was probably a good thing

that they did.

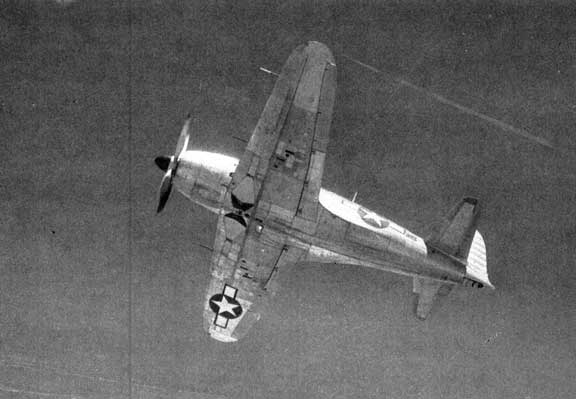

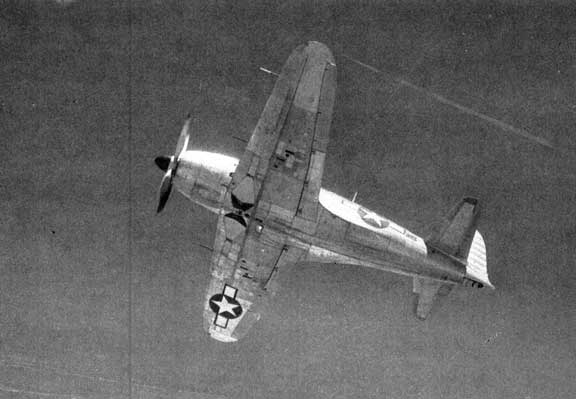

In flight over Southern Indiana

Kawasaki's Ki 45 Toryu

(Dragon Slayer) codenamed Nick, represented an old design that survived on

the Japanese Army Air Force rolls, mainly because its robust airframe

could be put to a number of tasks, which had been unforeseen when Nick was

designed in 1937. The U.S. and Britain learned early in WW II that

twin-engined, multi-seat fighters and attack planes could not compete with

single-engined fighters and, moreover, were not worth producing, unless

they could carry substantial bomb loads. The British Mosquito was the only

exception, but even that exception could carry prodigious weights at

speed. The Nick's bomb carrying capability was not much better than a Zero

fighter's. It was not particularly fast, ranging between 300 and 330 mph.

in its various models. However, it did have room in its fuselage for heavy

armament and when the B-29 bombers began coming over Japan at night, it

was the only night interceptor available with a service ceiling over

30,000 ft. and a range of over 1,000 miles.

It could also accommodate

radar and, as a result, the night fighting role was thrust upon it. As an

attack bomber it was a dud, but as a nightfighter, it proved a welcome

surprise, much like the German Me 110. It is shown here being evaluated

after the war and, below, during its combat life, with twin 20mm cannon

installed to fire upward into the bellies of marauding B-29s. The Necks

type starter arrangement in the last photo was typical of all Japanese

Army types which were conceived during the period of 1937-1941. The last

meaningful fighter interceptions of the war were conducted in a Nick by

Goldin Isamu Kashide, who watched the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

from one.

At Freeman Field

Indiana's White River below

Probably not at Freeman Field

Probably not at Freeman Field

NAKAJIMA KI 44II SHOKI (TOJO)

China, 1943

Speed: 376 mph at 17,000 ft.

Service Ceiling: 36,000 ft.

Range, clean, at fast cruise: 565 miles

Armament: Two 12.7mm machine guns, two 40mm wing cannon

Ki 43 Oscar

Development of Ki 44

Shoki (Tojo) interceptor (top) from basic lines of Ki 43 Oscar (middle

photos) bears striking parallel to lineage of our own P-35/P-47

Thunderbolt, and took place roughly during the same time frame. Larger

Nakajima 14 cylinder radial, provided 50 percent more power to what was

basically the same airframe, thus the enlarged and more rotund forward

cowling, which in profile reminds one of the early P-43 Lancer. Although

Tojo was not particularly maneuverable, when compared to orthodox Japanese

fighters, it was the best climbing plane in the Army Air Force and its

heavy armament made it that arm's most efficient bomber attacker, provided

it could get close enough to fire the 20 rounds from its two 40mm, low

velocity cannon. Two aircraft at bottom of page are training Ki 44s with

old style tubular gunsight. In combat, a reflector sight was employed.

At Freeman Field

At Freeman Field

At Freeman Field

May be at Freeman

Field. The B-32 was known to have been at Freeman

If the Ki-44 was an

interim Nakajima design to supply an interceptor for the Japanese Air

Force, the Ki-85 Hayate or Gale, was the best Japanese fighter plane of

the war and a true all around performer, ranking with the P-51 Mustang.

Debuting in the spring of 1944, first in China and then in the

Philippines, the Frank, as it was codenamed, fought a brilliant delaying

action. Although vastly outnumbered in the Philippine campaign, more Ki

84s were lost to faulty hydraulic systems than to enemy air action. With a

top emergency speed exceeding 400 mph., good armor plate, and up to four

20mm cannon, the Hayate also was possessed of exceptional range (over

1,000 miles) and could climb to 16,500 ft. in just under six minutes.

Photo at top of page shows a captured Frank being tested by the Technical

Air Intelligence Unit, Southwest Pacific Area. At middle left is one of

the first Service Test batch at the factory. Next to it is a newly

captured Frank, with a B-32 Convair Dominator behind it, while at the

bottom is a lovingly restored Ki 84-la, which once belonged to the

Ontario, California, Air Museum.

1. Nakajima B6N2 Jill.

Although a satisfactory performer, Jill's size and high landing speed

limited it to use on large carriers only. Although very similar to its

predecessor, Kate, two years of teething trouble delayed Jill's combat

debut until mid 1943, by which time attack aviation had gone far beyond

its limited state of the art.

2 & 3. Two views of Jill, both showing its most vulnerable aspects.

Four-bladed prop chewing into opponents, was its only means of frontal

defense, since Jill had no forward firing armament. Although a ventral gun

was installed on some models to fire to the rear, direct attacks from

underneath could also be made with impunity, and with disastrous results,

when wingroot tanks were exposed, as in this photo.

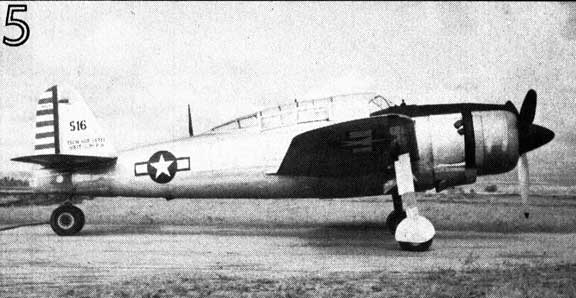

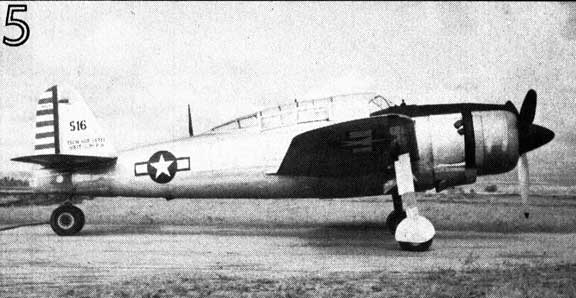

Aichi-Yokosuka D4Y3 Judy, also known as Judy 33, in flight over

Freeman Field. Although fast, with a top

speed of 360 mph., the Judy was badly handled during her first important

combat debut at the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June, 1944. Caught far

from the target carriers by energetic swarms of patrolling Hellcats, which

swept aside the Judy's escorts, she was shot down in droves.

5. Big and commodious, yet weighing just over 5,500 lbs. empty, Judy had

phenomenal range, nearly 2,400 miles in the liquid-cooled engined D4Y1,

1,800 miles in the -3 radial engined version, with tanks. Nevertheless,

bomber was obsolete. Her payload was light: 700 lbs. She carried three

crew members; she could not protect herself from attack, and represented

the type of plane U.S. Navy planners had abandoned by 1942.

Over Freeman Field

At Freeman Field

At Freeman Field

6. Fast, maneuverable,

fully protected and heavily armed, the NIKI Kawanishi Shiden (Violet

Lightning) codenamed George, was the best Japanese naval fighter of the

war. Almost as maneuverable as the Zero, it was much faster, carried four

20mm cannon, and did not fall apart or explode after one or two strikes.

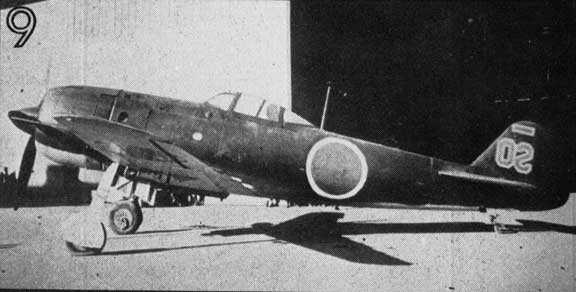

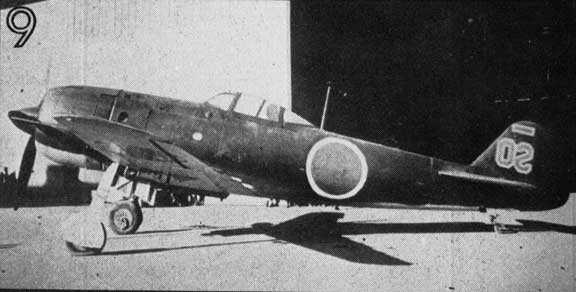

7. In one of WW II's most unlikely non-sequitors, George was developed

from a fine, but superfluous floatplane fighter, Kawanishi's N1K Kyofu

(Mighty Wind) codenamed Rex. It had been designed to provide air cover for

Japanese landing forces, but although fast (300 mph. at 18,000 ft.) a

floatplane fighter was no match for single engined enemy fighters

operating without the drag from one large main, and two outboard floats.

8. Thus, when the A6M Zero began to approach the end of its stretch, it

was decided, in an alternate type of solution, to reconfigure the Rex into

a landplane fighter. Within seven months, the X-1 prototype (shown here)

rolled off assembly lines, its distinguishing feature the absence of an

airscoop below the cowling.

9. The prototype appeared in December, 1942. By the time protection

aircraft had their bugs worked out, it was late 1943. Never intended to

fly from a carrier deck, the commitment of the Japanese Navy to the

building of 1,435 Georges, admitted that it would now go over to the

defensive. Troubles with the Nakajima Homare engine delayed really full

scale production, and when these were finally ironed out, B-29 raids

crippled the two major plants turning out the Shiden. For the U.S. it

proved a blessing. With a speed of 370 mph. capable of hauling 2,000 lb.

of bombs, or rockets, a battery of wing cannon, and brilliant handling

qualities, the N1K1 shown here at the Air Force Museum, was a deadly

competitor.

Successor to the B5N

Kate, was Nakajima's B6N Jill. Basically the same aircraft, but with a

much more powerful engine, Jill may have been 50 mph faster, but with puny

defensive armament, she was a set up for Hellcat and Corsair fighters.

Designed in 1939, the aircraft did not go aboard carriers until 1943 due

to a rash of landing accidents involving weak arresting hooks.

Greatly influenced by the

U.S. Army's A-18 twin engined attack plane,

Kawasaki Ki 45 Nick, a two-seat, heavy attack fighter was in production

for more than five years, after a long and frustrating testing phase.

Designed in 1937 as an answer to France's Potez 63 series and Germany's

110, Nick ended the war as a heavily armed nightfighter against B-29s.

At Freeman Field

One of Japan's fastest

attack aircraft, the carrier based D4Y Judy, designed by Yokosuka Naval

Air Factory, but built by Aichi, was the successor to Aichi's own Val dive

bomber. With a top speed of 350 mph. in the D4Y3 model shown here, Judy

was a swift striking machine, but a low normal bomb load of only 685 Ibs,

light armament, and lack of fighter protection hampered its career, which

began inauspiciously when two pre-production inline engined D4Y1-Cs went

down with the carrier Soryu at Midway.

Mitsubishi's J2M Jack,

was Imperial Navy's first try at a modern, land based interceptor that

sacrificed some maneuverability for climb and speed. An adjunct, rather

than a replacement for the Zero, it lost a great deal of time between

design and production, and illustrated quite unequivocally, that Japan

realized, as early as 1940, that it might be forced to fight a defensive

war. |