|

Berga |

||

|

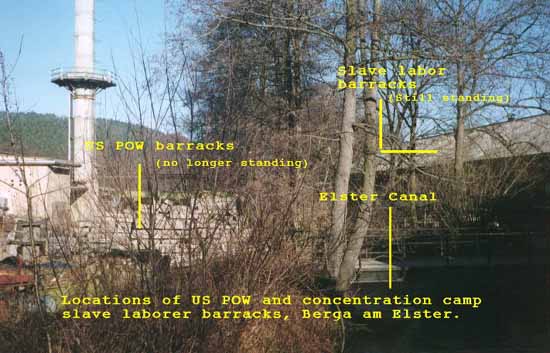

On February 13, 1945, 350 American prisoners of war arrived at a

concentration camp located outside the town of Berga (population 7,000) on

the banks of the Elster River. Four camps were located here: three P.O.W.

camps associated with Stalag IX-C (Bad Sulza) and comprised of soldiers of

various nationalities, and one civilian camp, a satellite of Buchenwald.

The civilian camp held 1,800 political prisoners who had arrived in

November of 1944 and who were forced to dig in tunnels to create an

underground armament factory.

As

was the case for other Nazi concentration camp inmates, work details

determined survival rates. Close to 70 of the 350 American P.O.W.s were

assigned to work as carpenters, locksmiths, electricians, or medics, or on

cleaning, burial, or food detail. The rest of them were sent to work in

the mines, digging tunnels for the armaments factory. By the end of their

time at Berga, the miners were working 12 hours a day, seven days a week.

They worked without masks, overcoats, or protective footwear, and were

beaten when their work did not seem satisfactory to their supervisors.

Cave at Berga |

||

A Former POW at BergaBy Anthony C. AcevedoGrade Rate or Rank:

Corporal The following narrative is based on a diary I wrote while being held captive by German forces during the Battle of the Bulge. I was a Medic for the 275th Infantry Regiment of the 70th Infantry Division and assigned to Company B. My story begins with the events leading to interment in a Nazi German prison camp, January 6 1945. As we were heading back towards Phillipsbourg we were told, "We’ve been cut off. The Germans have the place surrounded". I was still carrying all of my equipment in my backpack. My buddies yelled back to me to drop everything but my medical kits. I was scared and reluctant to leave my equipment behind. As we headed down the slope towards a gully I heard a voice, crying out, "...medic, medic. I’ve been hit! ". Then as I headed towards the voice I slipped on some branches and gunfire erupted. A shot struck my back but luckily the equipment on my back absorbed the impact and saved my life. My helmet fell off, but I was able to crawl, recover it and put it back on. I was then able to attend the wounded. Just then, down in the gully we noticed a cave with 4 to 6 Krauts that had been firing at us. One of our men shouted for mortar fire, killing all but one of them. Our men, killing the Kraut fired more shots. It was getting dark and soon we received word that we would not be able to go back to Phillipsbourg, the Germans had taken control of it. So, we headed up the hill to Falkenberg Heights. Several of our men were wounded and a medic was killed. I identified the dead medic - A buddy of mine named Murry Pruzan. We were without food for six days, the only thing in our favor was the snow which we ate. We were being surrounded. Our planes were bombing the hill below us to save us from being captured. German tanks had surrounded us and before we knew it, the Krauts wereon top of us. Shrapnel hit me and a Kraut poked me with his bayonet because I was too slow to walk. They made me take off my boots and walk on the snow bare footed. I don’t know how far nor how long I walked that day, but whatever it was it seemed endless. We were then put into box cars used for cattle. We were not able to sit or squat for several days and nights. The train was being strafed due to the "dog fights". Suddenly the train came to a stop, we got out of the box cars and walked to a place full of German soldiers. We were ordered to march to the gates of a concentration camp called Bad Orb-Stalag 9B. The camp consisted of prisoners from different nationalities, Africans, Spaniards, French, and Arabs to name a few. Hereafter I was designated as prisoner number 27016. One morning we were rushed out of the barracks and lined up along trenched dugouts. Behind us, the Krauts stood with their machine guns pointing to our backs. We had to stand outside all day in the snow. It was cold and some of us were bare footed. The Germans refused to let us put on our boots and as the day wore on some were so weak that they collapsed and fell into the trench filled with excrement. We later learned that the Germans wanted to know who had hatched the head of a cook with a meat cleaver. Food was so scarce that many were at the point of starvation and attempts were made to steal food. At the end of the day, a chaplain was able to convince those involved to step forward. Soon a couple of guys gave themselves up and immediately were put into confinement. They were not killed but punished severely. The rest of us were sent back to the barracks and placed under closer watch. A few days later, in the morning, we heard the sound of barrack door chains rattle. Three SS troopers walked in with their machine guns pointing in all directions, behind them a Gestapo Field Marshall walked in wearing a long leather black coat, tall boots and a monocle over his eye. It was just like in the movies; he looked all around studying each of us while he smoked a cigarette with holder at the other end. Finally he motioned towards me pointing with his finger. The German guards pushed me to follow him. I was the only one singled out. We entered a room furnished with only two chairs and a table. He sat on one side and I at the other, then immediately began to interrogate me. He said, "You medics know what’s going on behind the lines!" I told him I knew nothing and said all I know is my name, rank and serial number. He just laughed at my answers and said, "No, no ,no.....you know something!". I repeated I knew nothing of what was going on, "I’m only a medic". He countered with, "Oh yes you do! I’ve heard this story many times. You know something. Look, I know all about you." To my amazement he proceeded to tell me that I was born in San Bernardino, California and lived in Pasadena, California, with my cousins; that my parents moved us to Durango, Mexico; knew that my father was a civil engineer and had been commissioned by the Mexican Government to construct airplane landing strips for U.S. forces and was also involved in a PT boat project with an associate out of Texas; and knew of two employees that worked for my father. He added, "Isn’t that the truth?". I said, "I don’t know. How do you know?". "Look, I’m not dumb!", he responded and spoke in both English and Spanish, fluently. At this point I felt pinned but maintained my composure as best I could. He continued, "You left Mexico when you were 17 to return to the U.S. to study medicine. You decided to enter the Army. That we know. I also know that your father had his two employees arrested" Two friends and myself discovered that two of my father’s employees were spying for German U-Boats docked in the Sea of Cortez, Baja California, Mexico. One of my friends had studied Morse code and had detected the messages while we swam next to a building where the code was coming from. When my father made the discovery he had them immediately arrested. As the field Marshall continued his interrogation, he told me he also knew of a Schweader family and a sailor cousin of theirs who deserted from the Graf Spee German battleship which fought the battle of Montevideo. He made it to Durango and subsequently sold my father a rifle. The family was part of a colony of German families living in Mexico. The interrogation went on. I was coerced and tortured with needles inserted in my fingernails. I felt numb all over. It was very painful. Realizing he wasn’t getting anywhere with torture, he gave up, then made promises to send me to medical school in Munich and give better treatment to my buddies and me. He told me to think about it. On February 6, 1945, we heard fighter planes over our barracks. A dogfight ensued. It was a P-47 with a German fighter. Bullets sprayed all around and some hit a brick wall. Two of our men were hit and killed. In the course of that event the clock tower was hit and stopped at exactly 12:00 noon. That afternoon, plans were being made to move us out and divide us into several groups from camp Bad Orb to other areas. We had heard that their intent was to segregate American Jews from the other prisoners and that this new location would be a better place to stay. There would be more food, better living conditions and more freedom. For some unexplained reason I was included among them. Shortly thereafter, we had orders to stand outside of our barracks. About Three hundred-fifty of us were assigned to move out to God knows where. The Krauts spat, kicked and swung rifle butts at us because we wouldn’t move fast enough. We were ordered to get into boxcars and traveled several days and nights. On February 8, 1945, we arrived at the new camp. It was called Berga an der Elster. Berga was considered a mining center with caves and excavated tunnels for what appeared to be gun emplacements. We soon realized that it was nothing but a SLAVE labor camp. The worst was yet to come. Prisoners were being murdered and tortured by the Nazis. Many of our men died and I tried keeping track of who they were and how they died in my diary. During this time of confinement, we only ate 100 grams of bread per week made of saw dust with redwood bark. Just enough to barely stay alive. At 3:00 AM they had me and another buddy go for the "tea run". The tea was nothing more but dry weeds and shrubs boiled in water. I was told that the soup we ate was made from cats and rats. Conditions were so poor that disease was prevalent and many soldiers were very ill. One of our men was dying of diphtheria I tried convincing the Germans to let me perform a tracheotomy operation by boiling and sterilizing my fountain pen. I told them that his life could be saved. Instead, one of the guards responded by striking a fellow medic and me on the jaw with the butt of his rifle. On one occasion I remember a Commandant named Metz presenting us with a supposedly famous German boxer who had fought Joe Louis. He was dressed in a SS uniform and told us he was going to help us, which he lied since we never heard from him again. On March 20, 1945, a fellow prisoner named Goldstein was shot and killed for attempting to escape. That day, when his body was brought in, I was ordered to testify that I witnessed Goldstein’s escape and to claim he was shot for that reason. Not only had he been shot in the upper torso, but I also noticed upon closer examination, a shot to his forehead. The hole had been filled with wax to cover up the SS troops use of wooden bullets. I managed to acquire some of these bullets, but during my hospitalization I lost track of them. Others had been shot in the same manner as Goldstein. This I knew after having also examined them as well. Since efforts were being made to escape, we were ordered to remove our clothing before bedding down to prevent anyone from escaping. While naked I was ordered to take the clothing outside to a shack. We slept unclothed, two to a bunk and without heat, constantly threatened by the Germans. Sometimes we were able to find broken glass and use it to shave with, but better yet to help remove the white lice. We were always breathing and eating dust and dirt from those tunnels. Many of us could not tolerate the torture. On April 3, 1945, we had learned that American and Russian troops were about 100 km away and were closing in. The Germans were preparing to evacuate us. On April 6th we started to march out of the camp. Many of the men were becoming increasingly ill and suffering from malnutrition. Rumors circulated that we were heading towards the Bavarian Mountains, Hitler’s Eagles Nest. It turned out to be a death march. Up ahead of us we saw many political prisoners, women and children. They were being machined gunned down while trying to escape. Shots were fired from both sides of the highway in what appeared to be an ambush. It was a massacre. The Krauts also made use of remote controlled miniature tanks. Our men started to die one by one. It happened so fast that I couldn’t keep track of all of them. We continued to march and took turns pulling and pushing a cart of 10 to 20 injured and sick soldiers. The night was spent in a barn outside the town of Hof. Ground activity had now escalated and we knew that our boys were getting closer. The Germans made us keep marching and I fell back to help the sick. The march lasted and continued until April 22, 1945. That day while I waited in a soup line, one our interpreters cried out that we were to move out immediately! We could hear small arm fire in the distance. The guards yelled out, "Rouse! Rouse!", but we acted as though we were too ill to move. I laid down on the ground as a German Captain pulled out his pistol yelling for everyone to get up and go. By now General Patton’s tanks had moved in. The guards started running and the officers did the same. Some of the guards came up to us and gave up their weapons pleading for mercy. We were finally free! Everyone was excited and breathed a sigh of relief. We had been liberated! I had lost so much weight that I was down to 85 lbs. but thankful to God I had made it. Today April 24, 1945 we had our first good meal. I was in the hospital and reflected on the men who had not made it. Of the original 352 prisoners from Berga, only 170 survived [Editor's note: The actual total number of prisoners was 350 and the total number who survived is not certain, but probably closer to 270]. |

||

| From: Andi Wolos & Bob

Necci (POW-MIA InterNetwork) Re: POWs and the Holocaust Date: April 17, 2001 "A Filmmaker Remembers

G.I.'s Consumed by the Holocaust's Terror |

||

|

Captured GIs lived death camp horrors

firsthand Drafted into the U.S. Army in 1944 and taken prisoner in Germany soon before the end of World War II, Norman Fellman didn’t know much about the way the Nazis were treating Jews. He had heard that “there had been discrimination, and I might have heard of Kristallnacht, but we had no idea” of the extent of the murderous rage directed at the Jews, Fellman, who is Jewish, said. “Certainly we felt that as American prisoners, we would not be treated the way they were.” He was soon to learn that though the Germans treated no one well, they didn’t share Fellman’s belief that his American identity trumped his Jewishness. Fellman, who was 20 when he was drafted, was one of 350 American GIs — Jews, non-Jews the Germans thought were Jewish, troublemakers and even some random prisoners taken to fill the barracks — who were sent to Berga, a concentration camp about 60 miles from Buchenwald. Their story is told in two new books, “Soldiers and Slaves” by Roger Cohen and “Given Up for Dead” by Flint Whitlock. Fellman was sent to Europe in December 1944, Europe’s “coldest winter in memory.” Defending a hill near the Rhine River, his company lost contact with its battalion. After six days of fighting and five days after running out of food, members of the company destroyed their weapons and surrendered. The prisoners were herded onto a boxcar originally designed to hold 40 men or eight horses. “These cars had been used to move cattle, and hadn’t been cleaned,” he said. “These were the same cars that were used to take Jews to death camps.” Each car was packed with 60 or 70 men and the doors were closed, not to be reopened for four or five days. The low-ranking prisoners, including Fellman, were taken to a camp called Stalag 9B in the town of Bad Ohr, later said to be one of the harshest of the prison camps. A few weeks after their arrival, the prisoners were herded into the center of the camp, and any Jews among them were asked to step forward. Some Jews had thrown away their dog tags, which were marked with a telltale “H” for Hebrew. American prisoners assigned to do the paperwork when prisoners entered the camp “logged everyone in as Protestant,” Fellman said. But he didn’t want to hide who he was: “I don’t know if it was more pride than brains or whatever, but I had determined to step forward.” In February 1945, the men, including 80 Jews, were packed onto another cattle car and sent to Berga. They had to walk past a camp that housed civilian prisoners from Buchenwald. In Berga, the prisoners had to dynamite a hole through a mountain for an underground manufacturing facility. “You went in before the dust settled. The Germans had masks but you had nothing,” Fellman said. “If you didn’t work fast enough, you got hit. If you looked at one of them cross-eyed, you got hit. If the guy guarding you,” an SS man, “didn’t feel good, you got hit.” “We worked 12-hour shifts. We didn’t talk,” Fellman continued. “Guys were dying. We lost 40 or so men in the tunnels.” And then, “one morning we looked around and there were no guards. And then I looked over the crest of the road and there was an American tank with some GIs,” he said. “They were the best-looking ugly guys I ever saw.” Fellman was sent to an overcrowded Paris hospital. “People would look at me and I’d see horror in their eyes,” he said. “I hadn’t realized how bad I looked until I saw it in their eyes.” He survived, he said, because he had been in prime physical condition when he was taken prisoner. He had gone to Germany weighing 178 pounds but was down to 86 pounds when he was liberated. Fellman has gone on to have a good life. He retired after many years in the shoe business and, with his wife, Ruth, bought a farm in New Jersey’s horse country. Though Fellman is not fond of organized religion, he is deeply Jewish. “A refrain used to go through my head,” he said. “It’s from the camps. I’m a Jew born and a Jew bred, and when I die, I’ll be a Jew dead.” |

||

The Soldiers of BergaBy Mitchell G. BardIn 1945, more than 4,000 American GIs were imprisoned at Stalag IX-B at Bad Orb, approximately 30 miles northwest of Frankfurt-on-Main. One day the commandant had prisoners assembled in a field. All Jews were ordered to take one step forward. Word ran through the ranks not to move. The non-Jews told their Jewish comrades they would stand with them. The commandant said the Jews would have until six the next morning to identify themselves. The prisoners were told, moreover, that any Jews in the barracks after 24 hours would be shot, as would anyone trying to hide or protect them. American Jewish soldiers had to decide what to do. All had gone into battle with dog tags bearing an "H" for Hebrew. Some had disposed of their IDs when they were captured, others decided to do so after the commandant's threat. Approximately 130 Jews ultimately came forward. They were segregated and placed in a special barracks. Some 50 noncommissioned officers from the group were taken out of the camp, along with the non-Jewish NCOs. The Germans had a quota of 350 for a special detail. All the remaining Jews were taken, along with prisoners considered troublemakers, those they thought were Jewish and others chosen at random. This group left Bad Orb on February 8. They were placed in trains under conditions similar to those faced by European Jews deported to concentration camps. Five days later, the POWs arrived in Berga, a quaint German town of 7,000 people on the Elster River, whose concentration camps appear on few World War II maps. Conditions in Stalag IX-B were the worst of any POW camp, but they were recalled fondly by the Americans transferred to Berga, who discovered the main purpose for their imprisonment was to serve as slave laborers. Each day, the men trudged approximately two miles through the snow to a mountainside in which 17 mine shafts were dug 100 feet apart. There, under the direction of brutal civilian overseers, the Americans were required to help the Nazis build an underground armament factory. The men worked in shafts as deep as 150 feet that were so dusty it was impossible to see more than a few feet in front of you. The Germans would blast the slate loose with dynamite and then, before the dust settled, the prisoners would go down to break up the rock so that it could be shoveled into mining cars. The men did what they could to sustain each other. "You kept each other warm at night by huddling together," said Daniel Steckler. "We maintained each other's welfare by sharing body heat, by sharing the paper-thin blankets that were given to us, by sharing the soup, by sharing the bread, by sharing everything."

Photo courtesy of Mack O'Quinn"Surviving was all you

thought about," Winfield Rosenberg agreed. "You were so worn down you

didn't even think of all the death that was around you." He said his faith

sustained him. "I knew I'd go to heaven if I died, because I was already

in hell." On April 4, 1945, the commandant received an order to evacuate Berga. This was but the end of a chapter of the Americans' ordeal. The human skeletons who had survived found no cause to rejoice in this flight from hell. They were leaving friends behind and returning to the unknown. Fewer than 300 men survived the 50 days they had spent in Berga. Over the next two-and-a-half weeks, before the survivors were liberated, at least 36 more GIs died on a march to avoid the approaching Allied armies. The fatality rate in Berga, including the march, was the highest of any camp where American POWs were held—nearly 20 percent—and the 70-73 men who were killed represented approximately six percent of all Americans who perished as POWs during World War II. This was not the only case where American Jewish soldiers were segregated or otherwise mistreated, but it was the most dramatic. The U.S. Government never publicly acknowledged they were mistreated. In fact, one survivor was told he should go to a psychiatrist. Officials at the VA told him he had made up the whole story. Two of the Nazis responsible for the murder and mistreatment of American soldiers were tried. They were found guilty and sentenced to hang, despite the fact that none of the survivors testified at the trial . Later, the case was reviewed and the verdicts upheld. Nevertheless, five years after being tried, the Chief of the War Crimes Branch unilaterally decided the evidence was insufficient to sustain the charges and commuted the sentences to time served — about six years. Source: © Mitchell G. Bard. Forgotten Victims: The Abandonment of Americans in Hitler's Camps.. CO: Westview Press, 1994. |

||

|

'Berga: Soldiers of Another War'

The documentary film "Berga: Soldiers of Another War," the final work in the long and distinguished career of the late filmmaker Charles Guggenheim, reveals Nazi Holocaust atrocities inflicted on 350 American POWs "classified" as Jewish. Thousands of American GIs, including soldiers in Guggenheim's 106th Infantry Division, were captured by the Nazis during the Battle of the Bulge. Those "identified" as Jewish were shipped off to a satellite of Buchenwald concentration camp, where they suffered harrowing atrocities as slave laborers. Producer Grace Guggenheim, daughter of the filmmaker, will be online Wednesday, May 28 at 3 p.m. ET, to discuss the film and this little known story of World War II. Submit your questions and comments before or during the discussion. Ms. Guggenheim has produced over 20 documentaries for both television and theatrical release. In addition, she acts as Vice President of Guggenheim Productions, Inc., overseeing and managing all business and personnel transactions for the company. She graduated from Carleton College in 1982 and currently lives in Washington, D.C. "Berga: Soldiers of Another War" airs on PBS Wednesday, May 28, 2003 at 8 p.m. ET. (check local listings). Editor's Note: Washingtonpost.com moderators retain editorial control over Live Online discussions and choose the most relevant questions for guests and hosts; guests and hosts can decline to answer questions.

washingtonpost.com: Grace, thank you so much for joining us today. Why was telling this story so important to your father? Grace Guggenheim: Oh

boy, my father felt profoundly obligated to tell the story because he

wanted to give back to his fellow infantry men. And the complicated part

of it, as you know it's mentioned in the Post article, when I was growing

up, Charles always felt introspective about the fact that penecillin saved

his life at the last minute. Through training he'd developed an infection

in his foot and it turned into blood poisoning. I remember because it was

from his lymph node in his ankle to his hip. He described how the doctor

came in and said "put this man on penecillin right away." My guess is that

he was in the hospital for about three weeks. In those days penecillin was

given by an injection in your glute, so you really remembered that. SO I

only learned recently that penecillin was only being given to infantrymen

going back into battle. SO that was his first introspection. Knowing how

he is -- you learn later what could have happened and he learned that his

division had been in the battle of the bulge and the 106th had the highest

casualty rate -- so as he probably aged, that really hit him also. The

question was always what would it have been like for him. He was always

inquiring about friends and tried to find an army buddy of his who was a

Jewish friend and found out he'd died in a salt mind. And that thought

never left his mind. Washington, D.C.: Grace, your dad was unmatched in his ability to move audiences to tears with his films. But I know that he couldn't have done it without your incredible digging and investigative reporting, plus being at his side during the editing process. Can you tell us something of how you went about digging up information and names at the national archives, how you found the guys to interview, what that basic investigative process was like for you? Grace Guggenheim: You

might want to refer to my previous answer because that sort of explains it

a bit. Never any one route to unfolding a story and you really have to be

open to leads. The Archives were significant because they confirmed the

names of the men that went to Berga. The original roster was there. It

confirmed names, but not what division they were in. It had their prisoner

assignment number. So we had to go through associations and word of mouth

and the VA. And then you have to have some luck, too. Some we interviewed

were witnesses at Berga, for example, one of the civilians we got through

the Holocaust Museum in Washington. And that's why things like that are so

helpful. Richmond, Va.: Ms.

Guggenheim, Grace Guggenheim: I

only learned about a month ago that there was a film on allied airmen

imprisoned. THey were Brits, Americans -- I haven't seen the film, but

what's interesting is that it's a small group of men who were separated

from their divisions and got -- the French resistance took them in and

they got sent eventually to Buchenwald. So there's another story no one

knows that's even smaller than ours. Pittsburgh, Pa.:

Grace, Grace Guggenheim: You

can contact me at my office. Chicago, Ill.: Thank you for presenting this story and discussing the film today. Did you research for the film take you back to Berga, or what was once the site of Berga? What kind of feeling did that bring you? Your father? Grace Guggenheim: Good

question. We did go back to Berga. We made a big effort to back to the

places that remained. We did film at the original cemetary where the GIs

were buried and there were pictures of the original SS headquarters which

is now the town hall and the reenactment footage -- along the same road

they walked down every day. It was eerie going back to Germany. I thought

it might be kind of awkward. I started to feel a question in mind --

because we look Jewish and have a Jewish last name. We'd done a pre-scout

before and made friends with people in the town of Berga. And they could

not have been more helpful. We could only communicate through a

translator, but without their help we would not have had the cast of

eastern Germans who played the GIs. There is some resistance to older

people because they don't want to be labelled SS. When I did interview a

man in his 70s, his reaction was that I wasn't around during the war, so

it didn't make sense to him to continue the conversation. There's a lot of

German guilt and understandably. You have to live with that burden and I

feel for them and in contrast, the survivors who have to use a certain

amount of hate to get over their feelings of what happened to them, too. I

think overall, once they met us and realized we were nice people... but

also things weren't talked about either. Falls Church, Va.: How many survivors of Berga were you able to talk to for the show? Grace Guggenheim:

Obviously, we've located six years ago a lot of them. But we were only

able to AFFORD to interview on tape 40 of them and from those 40 we chose

about 12 and about five of those were witnesses. We would have interviewed

more. Alexandria, Va.: What has the response to this film been like? Grace Guggenheim: I

appreciate you asking. Obviously it's such a personal interpretation. But

all the GIs we interviewed were sent copies of the film because Charles

was still alive. But then he became ill quite quickly and that was an

important thing for both parties. But all of them felt indebted to Charles

for telling the story and they are grateful to him overall. Germantown, Ohio: My father was held and escaped from Berga during the Death March on April 20th. He is looking forward to watching the documentary tonight. I am always telling my children how proud and thankful they should be for their grandfather and others like him. Do you think your documentary helps people in being more respectful and patriotic? I think we have let our youth forget what it took to get us to this point of freedom. Grace Guggenheim: I

think it's an important question. I think this gets into a complicated

area. I think you're right in that -- first of all, World War II -- the

world would have been a different place. We would not live in a democracy

now. And our current generation and people today, it's hard to completely

embrace the war we've currently gone into. No one wants a life lost. It's

complicated when you're in the moment and we don't have full information.

All I can say is that we are so lucky to have men, women and journalists

willing to serve our country. I hope people get from the film that whether

war is justifiable or not -- I think that's the thing about Memorial Day

we've forgotten, that those who serve our country need to be given the

credit they deserve. We have the freedom because of those who served our

country. Washington, D.C.: What recourse did the U.S. government have when they found out the fate of these soldiers? Were any diplomatic efforts made to have them freed? Grace Guggenheim: It's

just like this story -- not very well known. These guys were liberated

around April 20 and 23 of 1945 in two locations, and exactly a month later

there was a war crimes investigation committee that went back to Berga to

exhume the bodies. There were a lot of unmarked graves. They also went

along the deathmarch to find more who died. They collected evidence for a

war crimes trial a year later. Depositions were taken -- a man named Vogel

whose nephew died at Berga -- he was a lawyer and pulled together a lot of

information. The conclusion of the trial, which took place in Dachau,

Lieut. Willie Hack was tried by the Russians and hung. He was basically

the guy in charge of the construction effort at the tunnels and under him

were the two SS that ran the camp, Metz and Marz, and Hack was tried in a

different place by the Russians and Metz and Marz were tried at Dachau by

the allies. And they were sentenced by hanging. And then their sentence

was commuted to life in prison and then again to 15 years for one and five

years for the other. My guess is that their sentences were immuted because

the U.S. government was bartering for information. My guess is that we

still had American POWs in Japan... I don't know. But their sentences were

lifted because there was a lot of bartering going on. Lieut. Hack was

given over to the Russians and they hung him. So they were known for being

really vicious. When we were in eastern Germany and traveled south and

stopped off at a restaurant and the rumor was that the home was owned by

the SS and that the Russians came in and killed him. Their depositions are

available at the National Archives in College Park. Grace Guggenheim:

1999, there were German reparations transferred to the U.S. for the

prisoners of Berga. Until that took place we were held back from

interviewing some of the survivors. They were, a lot of them, represented

by a lawyer. Washington, D.C.:

Grace, that's interesting what you said about the survivors feeling hate.

I happened to talk with one of them, just a wonderful old guy, and asked

him how he survived the ordeal. He looked at me and said, "Hate. You had

to hate to survive, then later you had to get rid of the hate because it

would eat you up. I realized there were good Germans, and some of them

actually helped us." How was it for these guys, talking with you and your

Dad? Was it tough for them, or cathartic? Grace Guggenheim:

First of all, all of these things are journeys and first of all, you do

have to create some form of confidence with people before they will talk

to you. Charles was a master conversationalist. He was one of these people

that made anybody feel at home. He was also a veteran himself. I would say

for most of these guys, they never had talked about it. Milton in our

film, he died three weeks after we interviewed him, had never talked about

this with his family. Phil Shapiro had blocked it out so severely, that

when we wrote him in 1996 it opened the floodgates for him that this had

happened. Pittsburgh, Pa.: Dear

Grace, Grace Guggenheim:

Unfortunately, it is finished, but because of the publicity of the film --

which we're so lucky to have -- not only Phil's wonderful article, but

generosity from other papers -- people are contacting me with information

and I'm holding onto it because Roger Cohen is writing this book on it and

I want to make sure he has everything he needs. There are still many

mysteries. We estimated how many died at Berga based on a medical journal

and other peoples' observations. One man went back to find where a

relative was buried and because of that we have those names. Another

person wrote and said their father died at such and such a place, and

that's piecing together the puzzle that no one can find out about. You

want to know all the answers but not know if you ever will. |

||

| Page last revised 11/29/2005 |