PARKER'S

RETREAT

I am writing this for my children so that some day they may read it

and remember their father. It is an adventure story of sorts, and it

has had a great effect on me.

After graduating from infantry Officer's Candidate School at Fort

Benning, Georgia, as a second lieutenant, on June 20, 1944, and

getting married three days later, I reported to the 106th Infantry

Division at Camp Atterbury, Indiana on

July 1. This division had been one of the better units in the United

States but had been stripped of all but a cadre of officers and

noncoms in order to provide replacements for the Normandy landings.

Some 10 of us from my OCS class were sent to it as part of the

process of building it back up to strength.

Morale in the division was not very good. There were good many jokes

about our being readied for Military Police duty in Germany or some

other noncombatant role. The jokes were based on the fact that we

were receiving a wild assortment of replacements, many of whom were

not fit either by training or description for combat. Thus, I was

given the first platoon of the antitank company of the 422nd

infantry and discovered that of my platoon, less than a third had

had infantry basic training. One private was a carpenter who had

spent the war making training aids and had risen to the rank of

sergeant in the process. He had suddenly been plucked out of his job

and put into the infantry, and had been demoted in the process. I

never knew why; but his morale was as one would have imagined, and

he knew nothing about the infantry. Another private had been a

pastry cook in some military establishment until a month earlier,

when he, too, had been drafted into the 106th. This story could be

repeated over and over again through the Division. Fortunately, our

noncoms were good, and we received an infusion of new infantry

replacement training center graduates just before we sailed in

October. Overall, the Division was not very effective, however.

Before going overseas, we were inspected by General Ben Lear, he of

YooHoo fame. Our division commander general, Alan W. Jones, was

reported to be anxious to get his unit overseas and get it into

action, and there was a certain amount of fudging about our

readiness. Two small incidents indicate the atmosphere. First, one

of my colleagues was given the job of testing units from another

regiment on night patrolling. The first unit he tested

performed abysmally and he gave it a failing grade, He was called to

Division Headquarters and told to change the grade to show that the

unit had passed. Second, we had in my platoon a .50 caliber machine

gun that had long since fired more than enough rounds to be labeled

class X and replaced. We tried in vain to get it replaced before

leaving Atterbury, but were told there wasn't time, and went into

combat with it. It fired perhaps a dozen rounds on the morning of

December 16 and then broke down irreparably.

In any event, we sailed from Boston on the Aquitania on October 12,

landed at Glasgow ten days later and moved into a bivouac at

Fairford in Gloucestershire. It was cold and damp, but we had rather

a good time for about six weeks until we were taken to Southampton

and put on little channel steamers (I had to stand up at the top of

the companionway and literally kick my men through the door to their

compartment, it was so narrow) and taken across to Le Havre. We

spent ten days in the mud and rain on a hillside near Le Havre and

then moved off across France in motorized column. On December 10 we

replaced the 2nd Infantry Division along a 27-mile line, just over

the border from Belgium into Germany.

The 422nd had as part of its sector

the Schnee Eifel ridge which runs roughly northeast to southwest to

Bleialf.

This had been a quiet sector and we were apparently being moved into

the line at this spot to give us a gradual introduction to combat

while the Second Division moved out for an attack to the south. The

422nd relieved the 9th Infantry and I inherited a very cozy position

in the village of Schlausenbach, where I had the task of defending

the regimental headquarters against tank attack. I had two 57 mm

guns in position on the northeastern side of the 'village covering

the approaches from Kobscheid and Auw. Our field of fire was

admirable and we had just enough defilade to protect us very

effectively against flat trajectory fire. The gun on the left was

commanded by Sergeant Michael Valovcin of Bridgeport, Connecticut,

and that on the right by Sergeant William Chappell) of Chicago. A

third gun, under Sergeant Arthur Wiegert of Overland, Missouri, was

detached from the platoon and set up near one of the Siegfried Line

bunkers in the Schnee Eifel, near the elevation known as Schawarzer

Mann.

My platoon sergeant (John Harrell of Bainbridge, Georgia) and driver

(Albert Kath of Janesville, Wisconsin) set up housekeeping in a

little farmhouse on the very edge of the village, about 50 yards in

front of our guns. We soon worked out a comfortable routine and

looked forward to Christmas.

We were subsequently caught in

the German offensive of December 16, which became known as the

Battle of the Bulge. The Bulge was the salient in the American line

of which we were the northern flank. The 106th was pretty well

eliminated from the fight. Of its nine infantry battalions, three

survived intact. Most of the rest of the Division was captured.

The following is from an account I wrote the following Spring.

On the morning of the 16th of December, I pulled the three o'clock

guard shift in our little farmhouse. I started a new pot of coffee

and began a letter to Jeanne. After a little time had passed, the

customary early morning barrage started, the artillery positions

were just about a mile behind me, and by nature of the terrain, the

shells came fairly low over the house. I could hear the very

encouraging sound of outgoing mail and was happily thinking about

the poor Germans who were getting killed with precision and finesse.

Finally, it seemed to me that the sound changed just a trifle, the

shells sounded different.

After fifteen minutes or so, I

realized that this was incoming freight, the Germans were shooting

back at us. And we all knew they didn't have any artillery left. I

expected the firing to die down, believing it to be merely

interdictory, but instead it increased in intensity and soon shells

were falling all over my little bailiwick. I took a look outside and

saw the town of Kopfscheid, a mile to my left, a mass of flames and

tracers, apparently a very strong patrol action. I knew that there

was a troop of the 14th cavalry in that town and being very fond of

the cavalry, figured that they would soon dispense with the

nuisance. Finally, when dawn came, I went down to my gun positions

to inspect them and see how the men were getting along under fire. I

was amazed to find that three shells, all of them duds, had landed

within twenty yards of one position. The men were down in their

holes, looking green around the gills. At the company CP we

discussed the matter and decided it was very good battle

indoctrination.

About 8 a. m. we found that a general attack had broken out along

the entire front and that there were Germans running around all over

the place, which was disturbing, to say the least. Later in the

morning, we found that we were cut off from Division and that our

artillery was no more. Also, we had very little food, water and

ammunition. That afternoon I had a very exciting fire duel with a

couple of Tiger tanks at the very extreme range of 1700 yards. My

gunners couldn't hit a thing, but neither could the Germans, and

everybody was quite exhilarated. That night a platoon of Tank

Destroyers came into Schiausenbach to help and it was very

encouraging, because I was beginning to think that if any tanks ever

attacked our positions, we wouldn't have much luck.

We strengthened our positions

and prepared for the worst. On the morning of the 18th, we suddenly

pulled stakes and made for the woods. Our rifle battalions were

attempting to attack back towards St. Vith, and we were to follow

them up if they made a breakthrough. They walked into a terrific

nest of 88s, MG 42s, mortars, tanks. and every thing else

imaginable. We began to consider the situation desperate. Up until

that time we hadn't worried a good deal as we had heard the Ninth

Armored was to make a breakthrough, that ammunition and supplies

would be dropped to us, and that Patton was on his way. Blissful

ignorance. When the rifle battalions were very effectively stopped,

the motor elements, with which my platoon and I were riding,

attempted to make a run for it and find some gap in the German

lines. We tore through one town and up a hill only to run into a

group of tanks which stopped us momentarily; then we turned and went

down the road. By some chance my company commander, Captain

Edward Vitz, was in the lead jeep and I was right behind him. As he

topped a hill, he ran over a mine and the jeep flew into the air,

bodies hurtling in several directions, and stray bits of equipment

littering the landscape. That stopped the whole column.

They were hopelessly snarled up

by that time and we knew we didn't have time to clear any mine

field. I ran up to the jeep and we found everyone alive; the first

sergeant and our radio operator were pretty badly hurt, but everyone

else was doing fairly well. We began administering first aid and

waited for developments. About that time the captain who was in

command of the column came up and informed us that we had just

surrendered, which didn't impress us very much as we were going to

run for the woods when night came and that was not far off. However,

when we thought about the fact that we could see Germans all over

the place and that we didn't have any idea where our lines were, we

had no rations, most of us had sore feet, and the forests looked

most inhospitable, we changed our mind, which was probably just as

well. Although I will always wonder what would have happened and if

I just lacked the guts to try.

About night fall we loaded the wounded on some trucks and took them

to a German field hospital; most of them were delirious and I felt

very bad about leaving them, especially two of the boys from my

platoon who had been shot in the leg. That night I slept on the

ground in an enclosure with about 500 prisoners and succeeded in

doing a bang-up job of freezing my feet.

The next day was the 20th, and we were a sad looking sight as we

marched out on the road in column of fives and started toward

Germany. That day we marched for 32 miles, through Priam and other

towns I cannot remember. We got no food or water but thought the

sugar beets we occasionally found on the road most delicious. Water

we drank from the ditches. And I thanked God many a time that the

United States Army gives you so many shots. Otherwise we all would

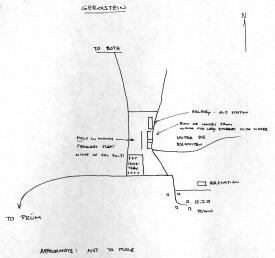

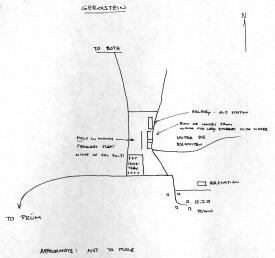

have contracted something. We reached the town of Gerolstein at 2

a.m. on the 21st - tired, hungry, and frozen. Here I ran into

Johnson, Prell, and Shapley from my company, also my entire platoon

less the wounded, and a number of other officers from the regiment.

Prell had attempted to escape but he ran full tilt into a German

tent and was recaptured. We slept on the ground for a few hours,

Shapley, Kastenbaum and I sharing my blanket. I slept soundly. At

daybreak, Johnson and Juster (cannon company) convinced me I should

go up to a nearby German aid station and get my feet treated, so

Juster lead me up to the place, pushed me into a compound and told

me to turn right. I took about three steps, when a Hauptmann came up

to me, grabbed me and pushed me in another column. I found myself

alongside Lt,. Howard Alexander, our Exec, and six other officers of

the regiment. I asked what was going on and they said, "We're going

to the train." Then the guards came along and handed us some

crackers and cheese and marched us off through the town to the

bahnhof. Here we loaded on 40 & 8 box cars full

1of manure and pulled out for

parts unknown. This was one of the last trains to leave Gerolatein,

and if I hadn't gone to get my feet fixed, I never would have made

it. Lady Luck had smiled again. After a day or two we came to

Limburg, site of a large transient camp. Here we waited until the

26th before pulling out, receiving very little to eat, and spent a

most unhappy Christmas.

On the evening of the 23rd, the RAF came over to bomb the industrial

and rail facilities at Limburg, and they succeeded in giving us a

very bad night. One bomb fell on a barracks full of American

officers at the camp and killed some 67 officers. Jack Kilkenny, who

was an usher at my wedding, was among these. We had about forty

casualties on the train; several of the cars broke open and the men

rushed out into an open field running for an air raid shelter, a

bomb lit in the field and caused a number of deaths and a larger

number of wounded. I found a hole near the train and dived into it,

finding myself on top of an American and a German soldier.

Nationality didn't seem to make much difference.

We left Limburg on the 26th with great rejoicing; we were actually

looking forward to a permanent camp. We crept through Germany for

five days, stopping frequently and always moving slowly. I might add

at this point that it is extremely uncomfortable not to be able to

lie down for nine days. Once during this leg of the journey I got

about half a cup of hot soup,2

I was almost sick from eating so much. But the greatest hardship of

the journey was not the physical but the mental - it was like

staring at a blank wall for a short eternity; when you're starving

and cold, your mind doesn't function properly and you can't keep

your mind on anything but food; I could always see a plate of

scrambled eggs and pancakes floating before my eyes and it eclipsed

all other mental activities. And constant preoccupation with

physical hardships reduces you to a kin4 of agonizing lethargy.

On the 30th of December we arrived at Stalag IV B, Muehlberg. We

stood in the open for three hours before finally entering the

delousing chamber, but it was worth it - for here we had the most

wonderfully hot shower of our lives. It was so hot that we all felt

faint and light-headed upon emerging from it. I was so dirty the

Germans sent me back three times before they'd let me get dressed,

each time it got better.

After the delousing we were processed and taken to a barracks. There

was no American compound at IV B so we were taken in by RAF

non-coms. They had hot tea and soup waiting for us, and water to

shave in. Those boys were wonderful to us. They gave up their own

beds, their food, and their cigarettes (which were as good as gold).

It was almost amusing to find that I was in a barracks with my

platoon. How that group managed to stick together I don't know, but

it certainly was good to see them, even if they were ragged and

haggard. I'll never see a nicer, more cooperative platoon.

The English had been prisoners for up to five and a half years and

they had prison life down to a perfect routine. There was no

quarreling and everyone helped his neighbor. We greatly admired

their system and decided that Americans could never do as well. We

were astounded to see beautiful cakes all over the place - I mean

cakes like you find in a bakery. By many devious methods they had

obtained flour and sugar, and using powdered milk and jam from their

Red Cross packages had baked some masterpieces. It seems that this

was an annual occurrence, that every Christmas and New Years they

had a big blow-out. New Years eve they had a show, which we

attended. There was one female impersonator who was so realistic

that we almost fell out of our seats. And the show itself was far

better than any USO show I've ever seen.

We stayed in the IVB ten days, receiving one Red Cross package

(English) per two men. These packages were our life blood. They

contained powdered milk, chocolate, cigarettes, coffee (soluble) or

tea, biscuits, jam, processed meats, cheese, salmon or sardines,

primes or raisins, and sugar. Each box contained ten pounds of food.

They usually came every two weeks at most camps, sometimes they came

once a week.

While at IVB some more of the regiment came in. I met Jim Hesse,

from Wichita, who was an. old friend of some of my fraternity

brothers and he and I became informal "muckers", the English

equivalent of partner.

We left Muehlberg on January 8 for Of lag 64, a camp for American

officers at Szubin, Poland. That trip was fraught with trials, We

occupied half of each box car and the guards occupied the other

half. There was a barbed wire fence between us. When we had a "rest

stop", we either had to climb over the fence to the guard's door or

have them get out and open the door on our side.

I was the only German speaker in the car and a number of the

officers had violent diarrhea, which meant that every hour or so,

night and day, I would have to tell the guards that someone had to

go (including myself). Hesse was pretty sick and I will never forget

the night we went through Frankfort am der Oder, the train wasn't

stopping and Hesse had to climb over the fence, open the guard's

door, and with a guard holding on to each hand, shove his rear out

the door and into the wintry blast. It was funny even then.

We arrived at Oflag 64 on the 10th of January. I found that Colonel

Goode, who lived across the street at Ft. Leavenworth, was the

senior American officer, that each man got a parcel a week, that

cigarettes were plentiful and that it was colder than hell. Hesse

and I moved into a cubicle with 6 other officers. One a high school

classmate of my brother's, and another a good friend of Hesse's. I

got a wool undershirt and two blankets, got a copy of Gibbon's

"Decline and Fall" from the camp library, crawled into my sack and

stayed there, except that I contracted diarrhea myself and was

constantly running to and from the latrine, living in constant fear

of an indiscreet accident. I couldn't eat potatoes or bread, the

staples of our diet, and I was living on cheese and toast, trading

my other foods for cheese. I did make one chocolate pudding and it

was the most delicious chocolate pudding I've ever eaten anywhere at

at any time. We spent a good part of our time cooking exotic dishes

from our meager materials, and the goodies that were turned out of

things like biscuits, D-rations, and the never-failing powdered milk

would surprise many a chef. We all swore that upon our return we

would take our wives into the kitchen and show them how to cook on a

tin can using cardboard for fuel and next to nothing for materials.

But always I could see and taste scrambled eggs. Never did I want

anything worse.

When the Russian drive commenced, we all speculated on what the

future held for us. That the Germans would evacuate us we didn't

doubt for a minute, but as each day came and the Russians drew

nearer, we saw no signs of our impending departure other than a

constant stream of refugees pouring down the roads in wagons,

trucks, cars, carriages and on. foot. Finally, on the morning of the

20th, we were told to be prepared to move at any time. Frenzied

action followed, all sorts of costumes were assembled, people sewed

pockets all over their clothes, made little sledges and packs to

carry their belongings, rolled up their blankets, and dressed for

the cold march to come. I put on two suits of wool underwear, two

pair of wool socks, two sets of wool OD's, two sweaters, a field

jacket, and my trusty field coat, a wool knit cap and a towel for a

scarf completed the ensemble.3

Then came a flurry of eating - "bashing" was the term employed at

the Oflag to describe any consumption of food beyond the normal

routine amount. And bashing passed all bounds that night. We were

issued a new parcel and I knew that one was all I could carry in my

condition. So I finished the half a parcel left from the last issue.

I made a wonderful pudding, and ate one whole box of raisins

straight. It was wonderful but it didn't help my diarrhea. All of

the cigarettes we had stored were brought out, and there was a mess

of them. Many of the officers had received tobacco parcels from home

and we had cigarettes to burn. I had three cartons.

The next morning we marched out in the cold air and after much

preliminary stalling around started down the road, leaving about 50

or 75 sick under Colonel Fred Drury at the hospital. That march

clarified the term "rat-race" for me. There were approximately

twelve or fourteen hundred officers and they were spread out for

five miles. Everyone was carrying everything he owned, and as this

or that got too heavy, he dropped it along the way. There were

cigarettes and cigars, pipe tobacco, books, food, blankets, clothes,

and officers littering the road for miles. It was a mess. After some

16 kilo-meters of very painful trudging, we pulled into a large

Polish estate and were herded into the cow barns. Some of the men

complained of the smell and rather liberal distribution of dung, but

it was the first time I'd been warm in a month. We could get milk

from the cows, and I thought the smell was wonderful.

In the morning we were quite startled to learn that all of us too

sick to march would be left behind. Hease and I were both in

misery as a result of our bowels and feet - we didn't march. There

were about 200 of us who didn't. We moved into the mansion of the

place and bedded down on the floor, waiting for we didn't know what.

About 1030 that night, (or the following), a Sherman tank came down

the road with a Russian driver. It was cause for no little

celebration. Except that I was too sick and tired to care about

anything and I didn't get up to see the Russian. Besides, some of us

continued to think that he'd probably fail to recognize us and start

throwing a little weight around. But finally we decided we were

free. So what?

The Russians told us to wait and they would bring trucks to take us

to Moscow where we would eat from platinum plates held by Molotov

and Stalin, or so the general impression was. Three weeks later we

were still eating bread and soup and no trucks. For which I do not

blame the Russians; they were too busy fighting a war to release

invaluable trucks for a load of prisoners. Finally, growing weary of

inaction, Hesse and I and a Polish-speaking boy from Detroit named

Sito took off for Warsaw. I might add that there were only about

forty of the original 200 left by this time. And what with missing a

train and a number of other things, we even got behind the fort]

remaining.

The farm we had been at was

called "Wekheim" and was five kilo-meters from the town of Erin. In

Frill we stayed in a hotel and slept in beds. That was the first

night, the night we missed the train. The next night we slept in the

railroad station. And the following night we slept above a creamery

across the street from the station. The man who owned the creamery

and his family occupied a very nice apartment that must have cost a

pot full of dough. We actually had tub baths and the water was hot.

Also, we sat on a genuine white porcelain flush toilet. I don't know

which felt better, the tub or the toilet.

About 4 a.m. the following day, a train pulled into Exin and the

stationmaster came over as was prearranged, jerked us out of our

warm beds and placed us on the coal car in the rear of the engine.

We soon got tired of the cold and worked out way up to stand behind

the firebox and that with the engineer. Here it might be time to say

that in Poland at the time oft this story, and still

4 for all I know, there were no

scheduled trains, nor any passenger trains such as we know in this

country. You might wait fifteen minutes and then you might wait two

weeks for one to come. They were usually always ammunition or supply

trains returning from or going to the front. No coaches were

provided and all accommodations were a' la box car or, if you were

less fortunate, a flat or oil car. I have seen a flat car covered to

overflowing with refugees taking off on a five-day trip in the dead

of winter. Long exposure to such conditions has apparently hardened

the Polish peasant. Everywhere you saw refugees, babies, girls,

young men, old men, old ladies. It was not at all uncommon to see a

70 year old woman trudging down the road with a fifty or sixty pound

load on her back. I will never forget the time one old grandmother

asked one of the officers (six feet tall, 170 pounds) to lift her

load up on her back. He couldn't even budge it. She grunted in

disgust, threw it on her shoulder and walked off. Of course, the

officer was in a weakened condition, but she didn't know it.

Later in the morning we arrived at the oldest city in Poland, Gnesen

(Gniesno) Here we met the first group of American GIs.

They had been at Stalag III-C near Kustrin and were heading for

Warsaw also. At this time rumors were floating all over the place to

the effect there was an American Consul in Warsaw, Lublin, Odessa,

and every other locality you visited. The Poles were telling us

stories of American planes landing near Warsaw and carrying away our

comrades who preceded us. Then we met some French prisoners and they

had heard the same story over Radio Switzerland. No latrine ever

boasted more gossip. We hopped some open box cars in Gnieznoand rode

for a few hours to Wrzesnia where we asked about trains to Warsaw.

As always we got the same answer: "It's not definite, maybe an hour,

maybe a week." Well, what with missing about five or six trains, we

stayed two days in Wrzesnia. We probably wouldn't have gotten out

when we did had I not noticed that the French-men were suddenly

moving (without telling anybody - so they could get a good box car

with straw and maybe a stove) and we followed right behind them,

even to the extent of riding the same car. We were trying to avoid

an English speaking Pole, who had been a member of the Polish

underground and said he had assassinated some Gestapo leaders,

because he was hinting broadly about us smuggling him out of the

country. Which was all well and good, but for all we knew, he was a

Gestapo agent himself. I've forgotten how long that ride to Warsaw

lasted. I know I did enjoy it because the Frenchman found a stove

for the car and seemed to have a genius for finding fuel. Also, they

had candles and were all in all quite sociable. One of them even

told me I spoke German without an accent.

When we arrived in Warsaw on

February 22, we found nothing but devastation. The entire city was

demolished. It was actually frightening; you could tell that it once

was beautiful, but it was certainly a mass of wreckage then. We

walked across the Vistula on a temporary bridge and were then in

Praga, a suburb of Warsaw that was in fairly good condition. After a

few hours walking around we found the Polish Red Cross building and

got some soup. They told us that we were supposed to go on to Lublin,

but we also heard that the Russians were putting all escaped

prisoners in a camp there (Mydanek?) where all the Jews were

cremated by the Germans. We also found that they were collecting all

prisoners in Praga and sending them to the former Polish West Point

at Rembertow, about four or five miles out.

We didn't particular care to enter either of these establishments as

the food was practically the same as our prison rations and they

weren't too clean. We spent the first night at the Red Cross. Three

GIs came in with a sack full of sausage, cakes and doughnuts (which

our mouths had watered over as we passed them in shop windows but

which we were unable to buy as we had no zlotys (two cents American

money,, and each doughnut cost twenty-five zlotys) that they had

purchased with the proceeds of selling the bicycles they rode from

Germany. They got nine thousand zlotys for three bikes and they had

eaten up six thousand of them that day. But they were happy as hell.

I ate one of the doughnuts and it was delicious. Hesse and I swore

we'd get some of those or die trying; we never got them; we didn't

die either.

A little later a man came in and started trading for clothes, a GI

shirt was worth six hundred zlotys. He spoke English, so I went up

to ask him if he was trading for Belgian francs, of which I had five

thousand. He turned out to be an American who had been living in

France and was taken by the Gestapo. He was some sort of a

millionaire, or so he claimed, and after a little discussion, he

wanted me to go in business with him and open an American bar. We

were to work up capital by buying and selling the English pounds and

American dollars the GIs were bringing in to Warsaw, those two

moneys being the only ones that always had a ready market. I was

sorely tempted and would have liked very much to have gone into

business with him as he was a pretty sharp customer. He had come to

Praga with only his clothes and not a word of Polish, and by trading

had worked a coat up to three thousand zlotys and an apartment.

I was still debating about three days later when we were staying

with

a Polish moonshiner on the outskirts of the city. He was making a

sort of white lightening out of rye. It was really pretty good but a

trifle on the potent side, especially at the rate they drank it. We

had a merry time in that house, plenty to eat and drink, and a good

bed to sleep on. My mind was made up for me very rapidly when Hesse

took an inspection trip out to Rembertow and came back in a hurry

with the news that the Russians had made up a train there and were

preparing to load all the Americans and English in an hour or so and

take off for Odessa where we would catch a ship. We hurriedly

grabbed our belongings, ate a meal, and said goodbye to our hosts.

We got to Rembertow in the nick of time, four or five coming in

right on our tails, and loaded on the train. The accommodations were

a little crowded, but we didn't give a damn because we were going

home. It took us a week to get to Odessa. Along the way I traded off

my socks for two loaves of delicious bread. We also got some

supplies taken from a captured German warehouse. All in all, it was

a pretty good trip, the stove was hot all the time, and we got two

hot meals a day (cabbage soup and a sort of thick barley or rice

stew).

We arrived in Odessa about the first of March and moved into a

couple of abandoned mansions. The boys who had gone to Lublin were

there ahead of us and we had a sort of reunion. Also, a Major

General (Dean) from the Moscow military commission was there to meet

us and had American cigarettes, corned beef, chocolate bars, life

savers, preserved butter, and all sorts of various goodies. We were

just starting to eat again when an English boat came in with a load

of Russian prisoners. The suspense was terrible, but we finally

loaded after being in Odessa a week. When we hit the dining room on

the ship we would sit and eat white bread until we thought we'd

burst. It was our first real white bread and it tasted like cake. It

was wonderful. About a week later we pulled into Port Said, stayed

there a week enjoying the sights and the food. Then we traveled to

Naples, spent a week there, loaded on another boat and came home. We

all got 60 days leave and we were all happy to be back.

FINIS

1

An obvious exaggeration. The cars had recently been used to

transport horses, however.

2

in the Stuttgard Banhof.

3 I

weighed 134 pounds with all these clothes on, according to the

dispensary scales.

4

i.e., in June 1945.

Submitted by

Richard Parker |