|

James W. Gardner |

||

|

Shelbyville News Gardners mark 60 years Mr. and Mrs. James W. Gardner, Shelbyville, Indiana, will celebrate their 60th wedding anniversary with a family dinner at the home of their daughter. Mr. Gardner and the former Joan Loudenback were married August 4, 1945, in St. Paul's Methodist Church, in Rushville, by the Rev. Frank Geer. Mr. Gardner was a U. S. Army infantryman during World War II. He was captured during the Battle of the Bulge and was a German prisoner of war for six months. He has been a teacher, coach, counselor and assistant principal, employed at Manilla, Connersville and Shelbyville Central Schools. He retired in 1989 from Shelbyville Central Schools, Mrs. Gardner was an elementary schoolteacher for 17 years with Indianapolis Public Schools: 24 years with Shelbyville Central Schools: and three years in Muncie, Connersville and Manila. She retired in 1990. They are the parents of Lisa Beth Metzger. They have one granddaughter, Erin Grace Beyer. Mr. and Mrs. Gardner are members of First United Methodist Church and Retired Teachers' Association. She is a charter member of Alpha Delta Kappa Honorary Sorority. He is a member of Elks Lodge, American Legion, Purple Heart Association, 106th Infantry Division and Ex-prisoner of War Associations. (note: Mr. Gardner does not have email) |

||

|

AN EXPERIENCE THAT MADE ME APPRECIATE by James Gardner I was taken out of College and inducted into the Army February 23, 1943. Little did I know what was in store for me the next 3 years. I went through Ft. Benjamin Harrison Induction Center at Indianapolis, IN. From there, I was sent to Camp Walters, Texas for my basic training. My training was to take three months and then I would receive a furlough before shipping overseas. The training was very strenuous, but having just finished a season of basketball, I did not mind it. I was in good shape before I started the training. Upon finishing my training, I was sent to a staging area in Pennsylvania. I went through Indianapolis on my way (25 miles from home) but was not given any time at home. I remained at the staging area for a couple of weeks and then was sent to a P.O.E.--Seattle, Washington. Again, I passed through Indiana, but could not stop. I decided that I was going to take everything with a grain of salt from then on. (They said I would get a furlough before shipping over). I spent a couple weeks at Ft. Lawton before sailing for the Aleutian Islands. I never will forget the music they were playing when I boarded the ship. (Lena 1-lorne - Stormy Weather). It was very sad. The ship (if you want to call it a ship) was a Liberty Ship. Many of them had been breaking up in the North Pacific. It was a very rough ride. I slept in the alley-way connecting the two decks. I was taken to Atka Island in the Aleutian Islands; no trees, just a bare volcanic island. I was assigned for the time being with the 138th Missouri National Guard. Attu Island had just been secured and Kiska Island was next. I was to be a replacement for Kiska. They had been bombing Kiska Island for quite sometime. The Japs had left the island under the cover of darkness, fog, etc...but we did not know it. The island was invaded from three sides, but of course we did not find the enemy. The weather in the Aleutian chain cannot be described. It is where all the weather starts for all parts of Alaska, Canada, and the northwest corner of the United States. You did not venture out at times for fear of over-exposure and exhaustion. During the worst months we would not go out unless there were several of us going together. Many mornings we would have to dig out of the snow in order to get out of our huts. All dwellings were put six feet or so down in the ground with sod around them. The wind was bad. They asked for volunteers for a ski platoon while I was there, so I volunteered I had always wanted to ski, but I didn’t know I was going to be skiing with a pack on my back, helmet on my head, and a rifle on my shoulder. Many times while going across the island we had to tie a rope from one squad member to the other, because of the many blizzards. Finally, it came time for the Missouri National Guard to go back to the states. I was one of twelve members to go back with them. The others went to the South Pacific. I considered myself very lucky, but little did I know what I had coming later on. We docked at Prince Rupert, Canada, and took a train across British Columbia and down into the United States and on to Camp Shelby, Mississippi. This was done in July with wool O.D.s on. We did not get our cottons until we got to Camp Shelby. I thought, “Now I will get my furlough”, but 30 of us had to maintain camp while the rest went home on furlough. After 30 days, I got to go home. Before I left, the company clerk said that the 138th was going to be deactivated. “Where would you like to go?” I asked, “What camps can I choose from?” He mentioned Camp Atterbury. I said, “That’s 22 miles from my home -- put me down for Camp Atterbury.” I was glad to get home for the first time, but after talking with my father, who was the civilian head of a motor pool at Camp Atterbury, I knew I had made a bad choice in selecting Camp Atterbury. He said they were supposed to ship out (according to rumors) for Europe and combat. I hurried back to camp, but it was too late. I had called my shot! I was sent to Camp Atterbury and I could plainly see that I was going to cross my second ocean. We left for Camp Myles Standish, Massachusetts right away, and from there we boarded the third largest ship in the world at that time, the English ship “Aquitania” It was a biggie It took us about six days or so to cross We docked at the mouth of the Clyde River in Glascow Harbor The ship was too large -- too much draft for the harbor We loaded on smaller crafts for the trip up the river. We boarded a train and were taken down to an area close to Oxford, England. Here we marked time for a while allowing us to have our last passes, and for all we knew, maybe our last passes period, to Oxford and London. I did get to see London; it was still receiving a few V-2 rockets and we were shaken up by one while we were there. The Channel was a rough crossing, but we survived. We docked outside the harbor of Le Harve, France. Smaller crafts came out to get us. The harbor was full of sunken crafts of all kinds. We were loaded on trucks and were taken on into France. We bivouacked in an open stubble field, plenty of mud and rain. We took marches and trained for several days -- waiting for a call to replace or take up a position on the front. Being young, I did not worry too much about what might be in store for me. Finally, the call came and we were loaded in 2½ ton trucks and taken to the Luxembourg area. We walked the last several miles up to the front in the Ardennes Forest and finally relieved the 2nd Division. This front was somewhat silent at the time (1st of December) and the 2nd Division had built dugouts and were waiting for the spring push into Germany. We were in what they called the snow mountains or Schnèe Eifel. I was assigned to the Ammo Pioneer Platoon Hdq. Co.-2nd Bn. 422 Inf. -106 Division. My duties outside of guard and patrol duties was to ride a 2½ ton truck back to the regimental ammo dump and bring ammo up to the lines. There was snow on the ground and we were supposed to watch for patrols coming through (especially at night). Being in this situation for the first time was quite spooky. You said to yourself, “How in the world did I get into this mess!” Snow would drop off or out of the fir trees at night. While on guard, many logs and stumps were mistaken for a body at night and were pretty well shot up. Ha! Little did we know, and little did anyone else know, that the German build-up for the one last big push had begun~ “The Battle of the Bulge” which was the biggest land battle ever fought by an American Army. The German artillery started to increase. Buzz Bombs were going overhead (they sounded like a John Deere Tractor). They were headed for places in Belgium. We were lucky, the day before the Bulge started, to get our last load of ammo up to the lines; the road was cut off just behind us. I learned this year (1988) that the gunner on our truck (Chun-Chinese) survived, only to die 3 or 4 years after the war from after effects of prison camp life (T.B.). I had received a fruit cake somewhere along the line. I don’t remember how it got to me, or when, but I had it in my duffle bag. Someone said on December 15th, “maybe we had better eat that cake and not wait until Christmas”. -After thinking about this for a minute -- I said, “Let’s eat it now; we don’t know what’s in store for us.” That we did! The next morning all hell broke loose. We were ordered to fall back about a mile, which we did. It was about 10 or 11 o’clock the night of the 16th, that the Sergeant called my name. I was trying to get some rest in my cold foxhole when this happened. He had chosen me and two other fellows to take the colonel back to headquarters. It was dark -- the trails were wet and frozen in places and we were not happy to do this. We needed some rest for what was to come during the daylight hours. The headquarters was located in a concrete bunker; we had to wait outside. We were sure they had some heat inside, but we were not asked in. After returning from this trip, which was successful (did not encounter any Germans), I was called on for another little detail. By this time it was getting close to morning; there were six of us who were given orders to go back to the area that we left and find a wooden sled and bring the kitchen tent back. Now I ask you, do you think that a kitchen tent was that important -- since it wasn’t going to be used? We encountered some Germans on this trip, but one of the fellows who had been left at a crossroads was able to figure out a way to avoid them at that time, since we are outnumbered. We got the tent back -- don’t know what ever happened to it. Crazy things happen in the Army. December 17th & 18th -- More shells were coming in. The last communication from Division Headquarters was received (I think the 18th). We knew we were cut off. No supplies could be dropped because the weather was too bad. It was a matter of us getting pulverized. Our big guns had been silenced and we were at the mercy of theirs. The night of December 18th found me under a fir tree, trying to get some much needed rest; just at daybreak all hell broke loose! I was being covered up by fir bows; the shells were trimming the trees. I looked to the right; down an open area on the ridge, about one half mile away were many German Tanks firing point blank at us (direct fire). We had no tanks to counter, nor did. we have anything except maybe a bazooka or two. If you have ever been close to a Tiger Tank, you might realize how awesome it would be to receive direct fire from them (many ex-soldiers know what I’m talking about). Our position was not very good where we were, so our leader thought we would be better off on the other side of an open field We used a wedge formation spreading out Many times we were pinned down making this crossing Many were wounded and killed during this We crossed, a platoon at a time When we reached the other ridge we started to dig in, but we were getting a lot of tree bursts. I made a dive next to a log while this was going on The firing seemed to be getting closer All at once I left the ground. My helmet left me, as well as my gun. I had taken a tree burst. The tree was cut off about half way up by a shell. Besides concussion, I had been hit by several pieces of shrapnel. When I got my senses back -- I was looking into a German Luger. An S.S. Trooper, who looked to be 7 feet tall, was behind the Luger. I realized that things were going to be a little different from here on. My eyes met his; he did not pull the trigger, obviously, or I would not be writing this. Little did I know about Hitler giving the order before this all started that they were not to take any prisoners. Thank God -- this German had a heart. I had lasted four days into the Battle of the Bulge. Many did not last that long, but many lasted many more days. A lot of thoughts pass through your mind during times like these. How nice it was back home, how worried your folks and friends would be when they got the “missing in action” telegram. The German ordered me to get up. I did. I was hit just above the left ankle, and also a piece hit me in the left hand. I also was stinging some in my left buttocks; this calls for a little story~ later on. . .My left leg was somewhat stiff, but I forced myself to walk and hop and limp. My thinking was that as long as I could maneuver on my own they would be easier on me than if they had to help me. I saw what they did to some of the wounded! I was taken down the hillside to the town of Schoneberg, Germany, where I was put in a brick building with several other wounded G.I.s. The building was somewhat like a little red brick school house. The floor was concrete with some straw on it. Not very soft, to say the least. One of our Medics was captured with me and he had some morphine which he gave me. This helped to relieve the pain which was coming on, since the numbness was leaving. I slept for several hours and when I came to it was the morning of the 20th. The bathroom was a slit trench about one hundred feet from the building. The snow was about 6 to 8 inches deep; it had snowed during the night, Of course, I had to go to the bathroom. I hopped and struggled until I finally made it out to the trench. I had some problems, since I only had one good leg. To top it off, my shorts were stuck to my left cheek. I found out I had a good sized nick out of my buttocks. I finally made it back to the building and related my story about my shorts. Even though the fellows were all wounded, they had to laugh when I told them my experience. I checked my billfold and found out the shrapnel had gone through my billfold and cut a four leaf clover in two. The billfold turned the steel and this had helped. On December 21st, I was taken down to a German field hospital. On the 22nd of December, 1 was taken into a room where two German doctors looked at me. I was somewhat afraid as to what might happen. I had been seeing several fellows go in and heard lots of moaning and hollering. I first told the guard that I did not want to go in, that I was okay, but he pricked me with his bayonet. . .I knew he meant business, so I hopped in. The German doctor told me to get on the table, which I did. He then pushed me back on my back, but I raised up, so to see what he was going to do. I had made up my mind to kick him with my good leg if he tried something funny. I knew I would lose in the long run. He pushed me down again, and I sat up again. He then hit me across the nose with his instrument. I watched as well as I could. He ran a sharp instrument into my leg wound and opened it up so it would bleed. He did the same to my hand. My wounds. had begun to fester. He did not use any medicines -- he wrapped my leg and hand with paper bandages, and ordered me out. I took up my position on the floor and watched others go in and out, some coming out with less than they went in with. On December 23rd or 24th, I was taken out and put in the back of a truck with several other fellows. We did not know where we were going, but the trucks did not have a Red Cross on them. Trucks taking ammo to the ,front had the Red Crosses on them. Consequently, we were at the mercy of our own planes. The driver and his companion would stop the truck and dive for the ditch. We had to remain in the truck. We were very lucky again. We were taken to a German hospital train, such as it was, wooden bunks and one stove at one end of the car. At one end of the car was a big picture of Hitler. We had a middle-aged guard in our car. He was as nice to us as he dared be He would point to Hitler’s picture and say to us, “Him no good Him no good II Our food was very sparse -- black bread, some kind of hot drink, some cabbage and once in a while we might receive a part of a potato. We were on this train Christmas Eve We all attempted to sing a few So/vtc . Christmas came and the guard gave us each a half of a peach. In a day or so we reached another field hospital which was run by the French or at least there were some French people working in the hospital. We were asked many questions, but were not .forced to tell anything beyond our name, rank and serial number. Our bandages were changed -- more paper --no medicine. We were taken out, in a day or two, to some box cars. I imagine about all P.W.s got to ride in a box car at sometime or the other. There must have been 55 or 56 of us in this box car. We were locked up in this box car for at least six days. They would move us a short distance, and then use the engine for something else. We had a starvation diet and no water. There was one small opening about 6½ feet up, this opening was about 10 to 12 inches square with barbed wire over it. We obtained one cup of water from one of the guards. He must have gotten it from the engine, because it was very rusty. This was arranged by giving the guard a cigarette. Some of us had a few cigarettes on us. These were better than having money. I think I could have bought my way back to the American lines with a carton of cigarettes. At one stop we heard planes overhead. We lifted one of the fellows up to the window to see what was happening. He said that we would not have to worry -~ they were our planes. I said, “Yes, but we are in enemy territory and they are here to bomb and strafe anything that moves.” It wasn’t long until they started strafing; we all hit the floor. Our box car vibrated from this, and a few rounds went through the corner of our car. I’m sure they were after the engine which was two cars in front. of us. This was quite a hectic moment, since we could not take cover, being locked in the car.

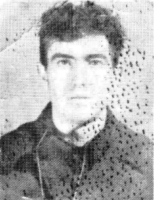

Showers were a thing of the past. They would turn the water on for a short period of time -- we would try to wash one piece of clothing at a time. I never felt clean all the time I was in the P.O.W. Camp. The barracks would hold about 150 or so. There were shutters on the windows, no glass at all. The bunks were wooden with wire fence like stretched across the bottom, two bunks high, sack material with straw in them for a mattress. Body lice were prevalent at all times. We used to spend an hour or so each morning picking the lice off us and also out of our clothing -- only to get back in our lousy beds and get more on us. This occupied some of our time I guess (picking the lice off). Every time I see a monkey at the zoo doing that it reminds me of those times in the P.O.W. Camp and the lice. Many of the fellows got sick and wasted away. Yellow jaundice took many of them. I was quite lucky, although I didn’t feel good while I was a captive, I did not contract a serious disease. I did think that gangrene was going to set in -- in my left leg; as I said before, it swelled two times its regular size and had some red streaks going up through it. Once in a while they would have sick call. The sick call room was several barracks from ours. I would hop from one building to the other until I got to the room where the German doctor and American doctors were. They would wash my wounds, put paper bandages back on; no antiseptic or medicines were used. (They had none). My leg had to heal and get better without the help of medicines. Somebody was on my side because, after awhile, it started to get better. The American doctor talked the German doctor into giving me a slip of paper; I guess you could call it a “sick-slip” and this kept me from having to go out and work in the fields or forests. I still have that -- 44 years later. Food was a very big problem. We were given about enough to keep us alive. We got two pieces of black bread, a cup of chickaree, sometimes a very small potato, sometimes a soup that looked like grass soup, sometimes cabbage broth (hot water with a cabbage leaf dragged through it). Two times during our stay in Stalag 2 A we were given an International Red Cross package. This package might have prunes or raisins, cheese, cigarettes (which we used to buy bread from the French), also several other little goodies. These parcels would be handed out -- one to 3 fellows. We would divide them very carefully; each had to receive the same amount. The cigarettes would be used (when we had them) to buy bread from the French. They worked downtown in the bakery and would smuggle bread out under their old dirty coats~ This bread was not wrapped, so it was exposed to everything. I would take up a collection of cigarettes from three or four fellows and then give the guard on our compound one cigarette to open the gate and let me cross the French Compound. I would walk (or hop before my leg healed) down the aisle hollering “brode” - “brode” until someone would roll back his blanket and expose some “brode”. Then I would barter with him trying to get the “brode” for as few cigarettes as I possibly could. They kept upping the price, which made us very angry. Upon making the deal I would then take the bread back to our barracks and we would divide it (again being very careful to divide it evenly). We did not eat lavishly! This bread was full of moisture and weighed heavy like a brick. They delivered it in wooden boxes and shoveled it into a bin. We couldn’t count the number of bugs or larvae that we ate or scooped out of our soup. We were always open for hits from the British night bombers. Most of the time they would drop flares around our camp to mark it so we would not take hits. There was an ammo dump not far from our camp. The British finally hit it and what fireworks. . .the whole sky looked like it was on fire! Many things happened while I was a captive of the Germans. The Russians probably got treated a little worse than the Americans. They lost fellows everyday. They buried them in huge graves -- many in the same hole. Much trading went on in the camp. Some of the fellows were trading wrist watches, pens, and cigarette lighters. Several got through the German search without losing them. Cigarettes were money and if you had cigarettes, you could buy more bread from the French. We did not have many cigarettes but, I think a carton of cigarettes would have been enough to buy my way out of Germany. I would say they could be sold for $20.00 a pack, if the money and cigarettes had been available. I had an extra cigarette at one time so I gave it to a “Serb” and he cut my hair with an old pair of scissors. (Some haircut!) Everybody quit smoking -- cigarettes were too precious to burn them up. Finally, we could hear the Russian guns getting closer and closer. The Germans were getting very nervous. . .they knew the end was near. They wanted us to move out and get out of the line of battle, but we held out to stay put. They finally gave in, sO the healthy ones took turns and dug trenches outside the barracks. All we had to do was go out through the windows (which had no glass in them) and into the trenches. We did this a few times when it got rough. Finally, shots were heard outside and they were hollering, “Ruskie come, Ruskie come”. We were a little scared as to what the Russians would do with us. Many of the Russians drink a lot of vodka. They received rations of it while fighting. We did not know what a drunken Russian would do. They told us that someone would be in to get us. We were about 75 to 100 miles from the American line which was the Elbe River. Our closest point would be Wittenberge on the Elbe. We wandered around looking for food, but didn’t have much luck. We finally got in a bread line downtown in Neubrandenburg. The Russians were using the bakery to make bread. German marks were all over the sidewalks. The mark was of no value at that time because of Germany’s capitulation. That is something a person won’t very often see -- a country whose money would not buy a thing. I picked up a couple of marks and got in the bread line. The Russian gave me a couple slices of bread and grinned when I handed him the marks. We (about 8 or 10 of us) finally decided after waiting several days that the only way we were going to get back was to find our own transportation. We set out to find some horses and a wagon. While we were doing this, we were still looking for food. While going through some of the buildings at the camp, I found my picture that was taken when I entered the P.O.W. Camp. I still have that picture today -- another keepsake and reminder that things could get worse than they are now. We finally found a team of horses and a wagon. We had a couple of farm boys who knew how to harness the horses, so we were ready to go. We were not sure how the Russians would take our leaving on our own, so we left before daylight one morning. We had a map that showed all the little trails and roads between Neubrandenburg and Wittenberge on the Elbe River. We tried to avoid the Russians as much as we could. We did not want to be mistaken for Germans and taken back into Russia to help repair war damages. We stayed. in German houses o& barns at night as long as the Russians were not using them. Many times we had close calls. We were afraid they would keep us from reaching our destination. We ate whatever the German people had available, which was mostly oats, just plain oats, with nothing on them. We saw many refugees on their way back home -- walking, leading animals, pushing carts etc Many of them had been caught in the line of battle; it was a. mess. We used up several, horses on our way back. They were hard to find The Russians were using them, or they had been killed by artillery shells. We saw many dead horses along the way. The horses were being used to pull the artillery pieces, since fuel was at a premium. Several German farmers did not want to trade horses with us, but we made the trade anyway. It took us 3 Or 4 days to make the trip back to Wittenberge. When we reached the Elbe we had two horse-drawn vehicles. We gave them to people going the other way. The Russians kept us for a while -- questioning us, but finally notified the Yanks. They came across the river with a barge. The bridges had all been blown up. That was some day when we stepped foot on that barge and headed for freedom once again. They gave us a piece of “white” bread. . . it tasted like cake compared to the gas-producing, infested, black bread we had been eating. We were billeted in German houses when we reached the other side of the river. “White” sheets, no less -- what a good feeling! Before we could sleep on the white sheets, we had to be de-loused. They ran us through the shower, de-loused us, set fire to our old, torn and dirty clothes, and gave us a new issue. What a wonderful feeling it was to be back among friends again with nothing to fear. After a day or so we were put. aboard a C-47 plane and flown to Reims, France. From Reims we were transported to Camp Lucky Strike, a tent city close to Le Havre, France. We waited here for several days on our ship to take us back to the good ‘ole’ U. S. A. One day while walking back to our tent from chow we heard that General Eisenhower was coming in, and in fact his plane was in the air ready to land on the strip close by. We went over to the air strip like many others to see if we could get a look at our General. We were much surprised when he walked from the plane with his aides on both sides of him, and stopped in front of us. I can not explain to you how I felt upon seeing him and the five stars on his shoulder. I thought this was a good climax of a nasty ordeal. He asked us how we were and if we were getting good food at Camp Lucky Strike. The funny thing about all of this was -- we had just been griping about the food, but when he asked us, we looked at the five stars and said, “Just fine, sir”. We were not going to complain to him on a little matter of bum food. I will always remember the smile on his face instead of the bulldog look that most generals had. Little did we realize that we were in front of a future President of the United States. It wasn’t long before our ship, the Admiral Mayo, was in the Le Havre Harbor. We boarded the ship and we were on our way to America. This was another great feeling! We had Victor Mature, the movie actor, on board ship with us. He was a first mate, or something. About every afternoon he would entertain us up on the deck of the ship. Maybe I had better say something about our living quarters on board ship. There were several holds in the ship reached by stairs. In the holds, or huge rooms, were bunk beds. These bunks were about three high -- the top one reached by a ladder. It was very close in these holds -- not much fresh air. The ship would rock up and down, back and forth, end to end, and side to side. You would hang on and try to get some sleep It was best to have a top bunk, because sea sickness was quite the thing. If you were on the top one there wasn’t a chance of being splattered by someone above. We had 5 gallon buckets for that purpose. They were not anchored, so when the boat would pitch one way Or the other, the buckets would slide and slop over. It got to be pretty slick and stinky before we reached shore. Shower water was salt water -- it was impossible to get a lather up. But the main thing was we were headed home. Never will I forget the sight of land; this was home -- the United States of America. I swore that they would never get me off this land again, because it is the only place to be!!!

James W. Gardner |

||

|

This year and next will see many special reunions of military units and battle associations observing the 50th anniversary of events that turned the tide during World War II. None, however, is likely to be any more special to Jim Gardner of Shelbyville and Leamon Hammontree of Dallas than their first get-together in nearly a half-century in Concordia, Mo., a few days ago. It was the first time the two men had seen each other since German troops overran their positions on Dec. 19, 1944, in the early stages of the Battle of the Bulge. Gardner and Hammontree — and several others — were captured. “That was the last time I had seen him. I was wounded so I was sent to another camp, and he (Hammontree) wound up in a different location,” said Gardner, a retired schoolteacher who taught 41 years in area schools including 31 years at Shelbyville Junior High School. Gardner and Hammontree had been about as close as two GI buddies can get when they were assigned to the Aleutian Islands campaign earlier that year. “He and a lot of the other soldiers in the company were Missouri National Guardsmen who had been called up as a unit. I was sent up there as a replacement,” recalled Gardner, 70. After the Aleutian campaign had ended, the unit was sent to Camp Atterbury near Edinburgh for intensified training before going overseas. “Hammontree and I were in the same company and platoon,” said Gardner. “Then we were sent to Europe, and the Battle of the Bulge began. Our unit was butchered. Four days into the battle, we were captured b3 the Germans and they sent us to different camps,” said Gardner. The Battle of the Bulge Association publishes a magazine for survivors. Gardner said he was reading a list of surviving members. “I came across Leamon’s name,” he said. Gardner began the correspondence and they both agreed to attend the Aleutian Friendship Reunion in Missouri. “When I saw him in the hotel lobby, I recognized him. Outside of being older, he hadn’t changed that much,” said Gardner. The next few days were spent reminiscing. Hammontree is a retired businessman. He and his brother had owned and operated a restaurant in Dallas. Hammontree was released from captivity before Gardner and they had lost contact with each other. American soldiers freed Hammontree; Gardner wasn’t liberated until a month later by the Russians. “When the Russians liberated us, we knew we didn’t want to spend much time with them. We had heard they had taken prisoners back into Russia, and we didn’t want to be among them because of someone’s vodka whim. They didn’t have much food, and we were the ones who didn’t get fed. “We stole a map, then took a team of horses and a wagon and headed for the American lines. It took us four days traveling through the woods and across country but we found our lines ... the map was accurate,” said Gardner. The Battle of the Bulge was the pivotal one that brought Nazi Germany to its knees. Fought in frigid conditions and against incredible odds, Allied troops held on and refused to accept defeat. The 10 1st Airborne Division and the 7th Armor arrived to divert enemy troops and reinforced Allied troops. The battle wasn’t over until Jan. 25, 1945. But Germany had lost 1,000 planes, 700 tanks, sustained more than 100,000 casualties with 35,000 killed. Allied losses also were high with more than 80,000 casualties, including 20,000 dead.

“It was the biggest single land battle ever fought by the U.S. Army. And, just as the atomic bomb shortened the war in the Pacific by months or maybe years, the Battle of the Bulge and the defeat Germany suffered cut down on the time the war in Europe lasted,” Gardner said. Battlefields such as Bastogne, Belgium — the primary site of the Battle of the Bulge — Normandy and Utah Beach and Omaha Beach and other French and European locations will be visited this year and in 1995 by former servicemen and their families. They are happy they have the good health, and the extra dollars, to make it back ... they know that many who were there won’t be coming back. They will be old men swapping stories with their peers and reliving their days of glory, because they have that right. Many commemorative events are planned. Those seeking information can write the 50th Anniversary of World War II Commemorative Committee, Suite 702, Crystal Gateway 4, 12213 Jefferson Davis Highway. Arlington. VA 22202. |

||

|

||

|

RUSHVILLE REPUBLICAN June

6, 1998

It was 53 years this April 29 since Jim Gardner of Shelbyville and Marion Ray of Bethalto, Ill., were liberated by the Russians from the German P.O.W. Camp,. Stalag 2A, Neubrandenburg, Germany. It was in December of 1997 that Jim received a telephone call from Marion. Marion had written Jim’s name down back in 1945, and finally was able to locate him 53 years later. On April 3, 1998 Jim and Marion, with their wives, met at the Ramada Inn in Effingham, Ill. It took several hours for them to compare notes and share memorabilia that brought back many memories of their experiences. They were captured by the Germans in December 1945 during the Battle of the Bulge. They were 75-100 miles into the Russian Zone when they were finally liberated, about six months later. After waiting about 12 days for transportation to take them back to the American lines they, with six other fellows, found a wagon and a team of horses and made their journey back to the American lines. The trip took four days. Back roads and trails were used in order to avoid the Russians. Food was wherever they could find it along the way. Walter Clayton, of Massachusetts, the navigator of the group had a map and directed the driver of the wagon through the woods and by-paths to their destination. They reached Wittenburg on the Elbe on Mother’s Day, May 13, 1945. They had to’ trade’ horses several times along the way. During their prison camp stay they were fed German Black Bread. Perhaps someone might want try this recipe copied from “the German Food Providing Ministry in 194l". 50% bruised rye, 20% sliced sugar beets, 20% tree flour (sawdust), 10% minced leaves and straw. Three of the eight fellows have been 1ocated, but Jim and Marion were the first to get together again. They are both corresponding with Walter Clayton, the air force fellow who was the navigator. They are hoping that someday they will locate the person who took a picture of this group when they arrived in Wittenburg. Perhaps the other five who made this wagon trip can be located and maybe they can all get together one more time to reminisce about their journey to freedom. Jim Gardner retired in 1989 following 41 years as teacher, coach, assistant principal, athletic director, and counselor. He is a former graduate and teacher at Manilla High School and spent his growing-up years in Rush County (1923-1943). His wife, the former Joan Loudenback, grew up on a farm near Mays, Indiana and attended all 12 years in Manilla Schools. She retired in 1990 after teaching in elementary schools for 44 years. |

||

Vet a hit at SHSBy Ron Hamilton

|

||

| Page last revised 11/12/2009 |

We finally reached our destination -- Stalag 2 A,

Neubrandenburg, Germany. My leg and hand were giving me fits by now; they

both were festered and my leg was taking on a bad smell. We were given our

only shower at this time. Coming out of the shower I noticed a black speck

in my leg wound. I pointed to this and motioned for a German medic. He

looked at it and went to get something to take it out. He pulled it out of

my leg (a piece of steel). He showed it to everybody in the room. He

thought he had really performed a bit of surgery. This did not solve my

problem; I had much pain for a long time and I thought I was going to have

blood poisoning and gangrene before it started to get better. I had to

keep my leg elevated for quite some time until finally it started to heal.

I was smelling like a piece of spoiled meat.

We finally reached our destination -- Stalag 2 A,

Neubrandenburg, Germany. My leg and hand were giving me fits by now; they

both were festered and my leg was taking on a bad smell. We were given our

only shower at this time. Coming out of the shower I noticed a black speck

in my leg wound. I pointed to this and motioned for a German medic. He

looked at it and went to get something to take it out. He pulled it out of

my leg (a piece of steel). He showed it to everybody in the room. He

thought he had really performed a bit of surgery. This did not solve my

problem; I had much pain for a long time and I thought I was going to have

blood poisoning and gangrene before it started to get better. I had to

keep my leg elevated for quite some time until finally it started to heal.

I was smelling like a piece of spoiled meat.