In

the beginning, in the 1930’s, there was a Depression.

Then the rumblings began in

1940, under the dark clouds of the impending WWII rolling in.

Although

I was employed by the Commercial Credit Corp. as an adjuster at this

time, jobs were not plentiful, and possibilities for upward movement

were not good.

Employers

were hesitant to promote or take on new hires, since the military

draft having been established and draft numbers were being called up

for the mandatory one year training, they did not want to train new

employees, only to lose them to the draft within the next few months.

I

then decided to get into the military draft and get it over with, then

come back home and “set the world on fire” and thus become rich

and famous.

Before

you wonder about this, I became neither!

Since

I had registered for the draft, #2001 in Burlington, Vermont, and very

impatiently waited, my number was never called, so I volunteered and

my new number was #V697, and I was placed near the head of the list at

that time.

Still

no call.

Again,

becoming more impatient, I looked into the possibility of joining up

with the local National Guard, which had been notified of imminent

Federalization. It just so happened that they had two vacancies –at

the bottom of the totem pole of course, as Private.

On

1 December 1940, I joined Company “K”, 172nd Regiment

of the 43rd Infantry

Division. This was a

temporary enlistment of one year, at which time we would be released

and would have satisfied the Draft requirements.

The

43rd Infantry Division was made up of units from Maine,

Vermont, Connecticut and Rhode Island.

The 172nd Regiment was from Vermont, and Co. K was

from Burlington. Each

major town in the State had its own Company, A through M.

I

was issued appropriate clothing – all used – and had to be tailor

altered, and used shoes. But

it was a start, and then individual equipment was issued.

So

here I was, a Buck Private earning $21.00 per month.

Quite a come-down from the $25.00 per week that I had been

earning! Talk about poverty

and survival wages!!

During

the days, we would work at our regular job, and every evening report to

the Armory to start basic training.

Incidentally, Co. K was a regular Rifle Company composed of about

120 men.

For

training, the Company had 3 1903 Springfield 30 caliber rifles.

We took turns familiarizing ourselves with these weapons.

We learned how to disassemble then assemble the piece, and later

learn how to do it in total darkness.

It wasn’t easy for a city boy who had never handled a gun

before!

Medical

exams were scheduled at various times along with shots, further training

each evening, and the time was starting to go by fast.

The

alert came in early February, that we would be Federalized soon, so get

your personal affairs in order and be prepared to leave Burlington, VT

for parts unknown.

We

were and we did.

On

24 February 1941 we were Federalized at the Armory, and this meant

regular working hours for Uncle Sam from 8 AM to 5 PM, then additional

training in the evenings.

We

reported to the Armory each morning just before 8 AM, and marched – in

ice, slush or snow! – to the Hotel Vermont for breakfast – real Army

chow – not the regular menu fare; marched back to the Armory and were

assigned duties, attended classes and participated in training of

various sorts that could be conducted indoors. We trained with wooden

guns and broomsticks. This

was all that we had. The

National Guard companies had only a very minimum number of weapons, as

generally they were not needed and were not available in these days of

peacetime. How we ever

learned anything, I will never know, but we did.

Shortly

the Company received one (1) M-1, Garrand 30 caliber rifle to train

with, and learn disassembly and assembly.

Yes, and in the dark.

This weapon was to become the mainstay of infantry weapons all

during WWII.

Each

noon, we would march up to the Hotel Vermont for chow, then back to the

Armory for more classes and training.

Then each evening we would again march up to the hotel for chow,

back to the Armory and were dismissed to go home – if we were all up

to date in qualifying for various subjects and weapons.

On

9 March 1941, we entrained at the railroad station – in Pullman cars

yet! – to go to some out of this world place called Camp Blanding down

in Florida. We all asked,

“Where in the World is Camp Blanding??

We

had seen a photo of it – green grass, waving palm trees, nice block

buildings we thought to be barracks and a couple of pretty nurses.

OH!! This was the place for us, far, far away from the cold and

snow!!

After

3 days on the train, we finally pulled into Camp Blanding.

What a God-forsaken sight. There

must be some mistake!?! Nothing

but white sand, a few sprigs of grass and a few pine trees bedecked with

dismal and dirty looking Spanish moss.

Getting

off the train, we were ankle deep in sand.

Dressed in our heavy wool uniforms with overcoats on, loaded down

with full field packs and toting barracks bags, we were lined up, and

our “smart” officers proceeded to “march” us to our designated

Company area. After 10

yards, it was a useless attempt to even try to stay in step in the ankle

deep sand, so we were allowed to break step.

Our

barracks bags were made of blue denim canvas and was our travelling bag

containing all of our extra clothing and personal items: ie shaving

items, shoe polish & brush, stationery and any other personal items

that were necessities. No

civilian type of clothing was allowed!

Generally they weighed about 50# - 60#.

Everything

that we were issued was referred to as “G.I.” for Government Issue.

Even the soldier became commonly referred to as a “G.I.”

Our

assigned company area, one half mile away, had not yet had its buildings

completed, except for the Mess Hall, Day Room and Company Hq.

We had to sleep out under the stars in our two-man tents for

about the next two weeks before our “permanent

homes” were built.

This was a wooden

platform about 16 feet square, with a flimsy frame siding with a pyramid

shaped top, and all covered with what was known as a pyramidal canvas

tent. In each one were 6

double bunks with a small coal stove in the center.

This was to be our home for the next year.

And so it came to pass.

It

was quite a challenge for raw recruits to attempt to set up a two-man

tent according to the manual. Tent pegs 8” long driven down into 1 foot deep loose dry

white sand did not serve their intended purpose.

The manual was written for hard packed dirt. Consequently, we just slept on our canvas tents and

covered ourselves with our blanket for the night. Not entirely rainproof!

But, we made the best of it.

Our

Commanding Officer, (C.O.), Capt. Arthur K. Tudhope, was soon reassigned

to be the Regimental Supply Officer.

He needed staff, so I being one of the low men on the totem pole,

and perhaps with the least amount of military training to date, was

detailed to work with him, along with several others detailed from other

companies. I was well pleased with this assignment, as I did not have to

take the long hikes,

some at night, and crawl around in the sand in training exercises,

regardless of the weather. “I

had it made” in this respect…

So,

things rocked along well for the rest of the year, trying to get used to

the intense heat, gnats, snakes and other unusual aspects of life that

we were not used to.

At

the end of my first 6 months, I was promoted to Private First Class.

Wow! My pay

increased to $30.00 per month!! But

then, we didn’t have too much to spend it on, and we didn’t have

much time to go anywhere to spend this great wealth.

We

had done so well on our maneuvers in Louisiana during the summer and in

the Carolinas in that fall, that on 1 December, we were told that we

could start packing up to go back home about the first of January.

OH!! Happy Day!!

But

then came the astonishing news on the radio Sunday morning, 7 December

1941, the day of infamy, the day that Pearl Harbor was bombed.

Needless

to say, right then we knew that we would not be going

home, but were to be incarcerated “for the duration”. True enough, a few days later, official word came down that

we were indeed “in for the duration”!

Things

began to change quickly then. More

new supplies, new guns and other equipment came pouring in.

Many changes were taking place in the company area.

The new C.O. was being sent to advanced school; the 1st

Sergeant was being transferred to the Air Corps; the Supply Sergeant

became the 1st Sergeant; and I, with my work background in

the Regimental Supply was transferred back to Company K and promoted to

Sergeant and became the Supply Sergeant for the Company.

In

early February we got our shipping orders to go to Camp Shelby near

Hattiesburg, Miss., to do some advanced training there, then to proceed

to Fort Ord, Calif., and await embarkation to the Pacific Theater.

In

March, I was called in for an interview by my former C.O., Maj. Tudhope

and the Regimental Commander and others, acting as a Review Board, to

interview prospective applicants to go to the Officer’s Candidate

School at Ft. Benning, GA, to take further advanced infantry tactics and

weapons training, to become a commissioned officer.

I never really got any basic infantry tactical training, and

precious little weapons instruction, although I did fire all weapons and

qualified with each one. I

was selected and shipped off to Ft. Benning to upgrade my status in life

and to become a commissioned officer.

It

was a struggle, competing with other men who had had many months or

years of military training and as instructors in their companies.

This was a 3 month course, thus the nomenclature upon graduation

was “90 Day Wonder”.

About

midway through the course, I came down with food poisoning, along with

several others. This

knocked us out, as the course would be too far ahead for us to catch up.

A short leave, and we were allowed to start back at the beginning

again in another later class. After

having 1½ months of this training, it was much easier the second time

around, and I successfully completed the course in September 1942.

Upon

graduation, I became a 2nd Lieutenant – a 90 Day Wonder –

and much to my disappointment at the time, I was assigned to Camp

Wheeler, GA as a Basic Training Instructor of draftees, just coming into

the military for 12 week basic training cycles.

Many of my graduating classmates were assigned directly to the 1st

Infantry Division, which had just pulled off the invasion in Africa.

That is where I wanted to be at the time!

“We’d” win this war and get it over with in a few months.

Little did we know of the heartbreak and suffering to come in the

next many, many months.

While

at Camp Wheeler, GA, I received my promotion to 1st

Lieutenant, became engaged, and was married there in a military wedding

on 1 March 1943 to a girl that I had met in Jacksonville, FL, (Mary

Olive Thomas) while I was at Camp Blanding.

Here it is 55 years later, and we are still hanging around

together!!

I

remained at Camp Wheeler until November 1943, and was then transferred

to the 30th Infantry Division.

They were then stationed at Camp Atterbury, Indiana.

I was then assigned to the 120th Regiment, Company

“M” a Heavy Weapons Company, as a Mortar Platoon Leader.

This was short lived, as the Company was then over-strength.

I was then temporarily assigned as the Regimental Packing and

Crating Officer, in charge of supervising the packing of all authorized

equipment of the Regiment, all of which had to be accounted for, packed

in standard crates, waterproofed and prepared for overseas shipment.

In

early February 1944, we departed Camp Atterbury, IN, to

–rumor-rumor-rumor. All flying fast and furious, but we finally arrived at Camp

Myles Standish, Mass. Here

we were quarantined for a few days, then allowed to go on pass.

At that time, my home being in Boston, Mass., that is where I

headed. Mary had gone there

to stay with my mother, for the duration or until I came back – if I

came back!?! So it was

quite a surprise when they saw me standing at the front door that night.

This went on for several days, then we got our alert for

shipping.

Our entire Regiment boarded the S.S. Argentina and sailed out

of Boston harbor on 12 February 1944, and joined in with the largest

convoy to ever cross the Atlantic.

We had an uneventful crossing of 10 days, and arrived in Glascow,

Scotland on 22 February 1944.

I

was with the detail in charge of unloading the ship and getting it all

loaded on to freight cars for shipment to southern England.

After a week here, and with all of the equipment loaded, we left

Glascow and went to Bognor Regis, on the southern coast of England.

My work continued here to supervise the unloading and

distribution of all of the freight.

Out of 140 tons of equipment, only one bundle of tent pegs was

lost!!

This

task accomplished, I then reverted to my original assignment with

Company M.

From

February until late May, we conducted many hikes, maneuvers and engaged

in a few live ammunition tactical problems in preparation for the days

to come. We were also

engaged in patrolling along the coastline in the area in which we were

billeted.

Then

came D-Day, 6 June. We knew

that this was the day and the real thing, after many false alerts,

because of the roar of the planes overhead from midnight onwards.

Fortunately

we were not in the first wave of the invasion.

This was assigned to the 1st, 29th, and 4th

Infantry Divisions. Later

this was followed by the 2nd, 9th and the 30th

Divisions. The 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions

were the very first troops – paratroopers – to land in Normandy , in

the early hours of the morning of 6 June.

These are the ones that we heard roaring overhead on the night of

5-6 June.

It

soon came our turn to go to the marshalling area where we were “locked

in” for a couple of days waiting for our scheduled time for embarkment.

Here we were out of touch with the outside world.

No one in or no one out, no letters, just marking time, and

checking equipment.

On

our somewhat rough trip across the English Channel, we were packed in

like sardines in our assigned LCI, (Landing Craft Infantry), and being

dedicated land-lubbers, each man was issued a “puke bag”, so as to

keep the vessel neat and tidy. Needless to say, a few of the “puke bags” broke or

overflowed, and the steel deck was a slippery and slimy mess. One poor guy, being very sick, could not make it to the side

of the ship to throw up overboard.

Being a “neat person”, and not wanting to mess up the walking

area any more, he dutifully threw up in his helmet.

Along with the “puke” came his false teeth!

What to do? It didn’t take him long to figure it out! Why quite

naturally he reached into his helmet and retrieved his teeth – and

then stuck them back in him mouth!!

Needless to say, in spite of being very hungry, we did not eat

any breakfast that morning!!

So,

the 30th Infantry Division, landing on 13 June, did not take

the brunt of the initial assault, but it was there early on, and

evidence of the terrific carnage that befell the predecessors was a

horrible and frightening sight.

As

for my own experience in the landing, it certainly was unique, and I,

along with my Company, had the dubious honor or experience of landing on

Utah Beach and Omaha Beach on 13 June 1944.

Somehow,

by error, the Landing Craft Infantry (LCI) that we were on was a U.S.

vessel, commanded by Canadians and under the control of the British, and

it became a part of the wrong convoy while crossing the Channel.

What could be more conducive to errors than this mixed control

situation?

Only

upon reaching and landing on Utah Beach did we realize that something

was wrong. We had been told that the Omaha Beach area was cleared and

out of range of mortar and artillery, and that we would land on a narrow

beach and would be facing substantial cliffs, and then we were to march

up through a draw between two of these cliffs.

Not so! Our approach

was to a wide beach with no cliffs, and sporadic mortar and artillery

were landing on the beach. This

was Utah Beach, not Omaha Beach, for which we had been oriented.

When the error was discovered, after disembarking the whole

battalion, we had to re-embark and get out of there.

In the meantime, the tide was going out, and as we boarded the

LCI, it became bottomed on a sand bar.

During this time, a few enemy mortar and artillery shells fell in

the area, but only one was a direct hit on our LCI and there were very

few personnel casualties. Another

nearby LCI came to our rescue, and with ropes, was able to drag us off

the sand bar, and we proceeded on our merry way to Omaha Beach, where we

should have been landed several hours earlier.

I

can well remember this incident on this day, as it was my 27th

birthday, and this was the biggest reception, although not friendly,

that I had ever received – even to date.

Prior

to disembarking from our LCI at Omaha Beach, we were sternly warned

that when we went over the side and down the rope ladder/netting, to be

sure that we had our rifles under control and well secured, and to hold

them high above our heads as we waded ashore.

“This was your protection of your life”!

No replacement rifles would be available for a long while.

Hang on to it and keep it dry!!

Over the side we went, and who was the first one to drop and lose

his rifle? Yes, our Company

Commander, Phil Chandler, the very one who had been so emphatic on the

warning to hang on to your rifle. He

didn’t hear the end of that episode for a long time, and he was very

embarrassed about it.

We then joined the rest of the 120th Regiment, and

started preparing for our first contact with the enemy.

We relieved a part of the 101st Airborne Division and

a part of the 29th Infantry Division, and planned our first

attack.

Again,

fortunately for me, Company M was still over strength – although it

would not be for long –and being a junior officer, was assigned duty

as a Liaison Officer between the Battalion Hq. and the Regimental Hq.

My duties here consisted of being a “glorified messenger

boy”, carrying messages and orders forward to the Bn. Hq. well before

phone lines could be established or radio contact made, due to being out

of range, batteries low or radios damaged, or at some times when it was

necessary to observe radio silence.

Sometimes it was rather difficult to find the Bn. Hq., as it may

have moved since I had last received directions or it may have been over

run and captured. We never

knew. Often it was

necessary to hunt for the Bn. Hq. in the night –pitch black- and trust

to luck that you did not run off the road, run over a mine, or over

shoot the front lines and end up in enemy held territory.

This latter happened more than once, but luckily we were able to

get turned around before being discovered.

Here

we had our introduction to “hedgerows”, something that we had never

trained for. Hedgerows are built along property lines, roads or fence

lines, defining fields. These

are composed of rocks and debris picked up in the field areas during the

plowing of the land, which is placed along the perimeter of each field. Through the centuries, with accumulation of dirt mixed in

with the rocks, trees and bushes started to grow.

They were generally shoulder high, and 8' to 10' through at the

base. Being a tangle of

roots among the rocks, they were nearly impenetrable.

Passage through them from field to field was accomplished by

dynamiting, or by tanks equipped with dozer blades or fork lift blades

which could then barely ram a hole through the hedgerow.

The fields were of all sizes and shapes, and very difficult to

attack and gain ground, as there were often Germans just on the other

side, and when you stuck your head up, you were a prime target and

easily picked off.

Artillery

was our major salvation in that we could bring down a barrage of

air-bursts, which were deadly to the Germans.

In

early July, we encountered one of the earliest major counter-attacks,

when the Germans hit us with all that they had, and made several

penetrations into our lines, but were finally stopped with out severe

damage to our defenses.

Prior

to this, we had been steadily, but slowly attacking and gaining ground. On several days, it was a 24 hour day contact and attack of

the enemy, and no one got much sleep, just sporadic cat-naps.

So much so that after a few days of this, I could just lean

against a tree and go to sleep – but not for long.

Finally

one has to give in, however reluctantly, to the forces of nature, and

due to the constant shelling and concussion, and being exhausted, I

developed what became known as “Battle

Fatigue”, formerly called “Shell-shock” in WWI.

After some personal denial and persistent persuasion by some

attending medics, I was evacuated by an adjoining armored unit.

Therefore, no record went back to my headquarters, and I was

presumed to be killed in action, or missing in action after several

days, or possibly taken as a P.O.W.

I

was evacuated back to a Field Hospital near Omaha Beach at the town of

Bernesque. I was treated for a few minor wounds, and was given battle

fatigue treatment for 10 days. I

then returned to my Regiment, where I was returned to the land of the

living, and assigned back to my previous duties.

The

day I returned, turned out to be another disaster for the regiment.

This was on 24 July 1944, at the beginning of the major, major

attack named “Operation Cobra”.

This was an operation planned for our Division to break through

the German defenses, thereby creating a major passageway and route for

the newly formed Third Army, under the command of General Patton, to

race through with his armor and race southward to Avranches and thence

onward to Brest.

All

of this action was commonly called the “Saint Lo Breakthrough”.

The

big plan was for the Air Corps to make a saturation bomb run just in

front of our Division, using the St. Lo-Perriers highway as a bomb line.

Our troops were moved back 1,000 yards north of this line as a

safety factor.

To

assist in defining the bomb line of the St. Lo-Perriers highway, our

artillery placed red smoke shells just south of the highway.

Unfortunately right at this time, a slight breeze came up from

the south, causing the red smoke to slowly drift to the north, and

directly on our troops in the front lines.

Over 1,500 of the Air Corps heavy bombers came over exactly on

time and on course, and dropped their bombs right down on our troops,

and as far back as the Regimental Hq. This is when I arrived back at Hq. from the hospital, and

everything was a chaotic mess. Even

the ambulance in which I had returned from the hospital was destroyed

with a direct hit of one of the bombs.

We

had a loss of over 150 men killed or wounded in this catastrophe, and

the attack was called off. Almost immediately, fresh replacements were

brought in to fill up the ranks and preparations were made for the

attack on the next day.

Since

all phone lines were totally destroyed and most radios suffered damage,

there was little or no communication between the Regimental Hq., the Bn.

Hq. and the Companies. This

is where my job became frantic, trying to keep messages and orders for

the new attack flowing in a timely manner.

So, this continued through the day and that night in preparation

for the attack the next morning at 11:00 AM.

The

same procedure was put in place the morning of the 25th, and

again, same bomb line, same red smoke put out and, same breeze came up

again!! Right on time the

1,500 heavy bombers came over and dropped their load right down on the

red smoke line, which was again right on top of our troops.

In this incident, we sustained 662 casualties.

Among those killed was Lt. General Leslie J. McNair, who was with

our 2nd Bn. to observe the progress of the attack, and to

visually inspect and assess the damage done the day before.

Again

I was kept extremely busy day and night carrying new attack orders

forward, and bringing back an assessment of the damage and casualties

incurred, as well as the specific plan of attack for the next day.

Damage and casualties were beyond imagination!

Bodies and wounded men were lying all around.

The wounded were being given aid by our medics, and arrangements

were being made for their evacuation.

Since

time was of essence at this point, and the element of surprise had been

lost, it was decided to go ahead with this attack with what we had, and

to do the best that we could. An immediate supply of replacements would not available for

another day or two.

At

the end of this day, the attack being successful, a wide breech was made

in the German defense lines, and almost immediately, Patton’s Third

Army began pouring through, and headed for Avranches against very light

resistance.

Our

Division was then pinched out of the line of attack and went into

reserve for rest, recuperation, re-supply and replacement of the men

lost in this action. But

only for a short time. In

two days we were on the move again, to a new battlefield.

At

this point, I was assigned to a higher level and became the Regimental

to Division Liaison Officer, executing the same type of duties, but on a

higher security level. This in turn took me further away from the front

lines, but still in a sensitive position, but doing much more traveling,

and enabling me to see more of the “big picture”.

Now

I want to stop here and interject a little bit about our personal life

style at this time, and in general from here on until the end of the

war.

Normally,

as we were taught, and as we moved

up and stopped overnight, one of the first things that we did was to dig

a fox hole or a slit trench. Fox

holes for long stays, slit trenches for 1 night stops.

Each man for himself, to pick his “spot” and dig, even

officers – of low rank! After we dug the slit trench which measured about (body

size), 6 ½’ long, 2’ wide and 1’ – 1 ½’ deep, we would dump

in some hay, straw, dead

leaves, (mulch), or pieces of cardboard from the food boxes in the

bottom, to soften the jabbing of the jagged rocks in the terrain.

We would then line this with our canvas tent and blankets. Not to worry about the rain!

Fox holes were a little more permanent and substantial.

Usually a few men would get together and dig a pit 4’ – 5’

deep, 6’ – 7’ long and 4’ – 6’ wide, big enough to

accommodate 2 or 3 men. This

then would be covered over with logs, boards, a door or what ever we

could find for a cover. This

was then covered over with 1’ – 2’ of dirt.

We would leave an opening at one end, just large enough to have

access to the fox hole. All

of this was necessary to protect us from shrapnel from the artillery

shelling at night. Staying

in houses at this time was not wise, as the Germans had them zeroed in,

and continually fired on them. So,

this was our sleeping quarters during the first two months of combat.

Often

we would utilize fox holes dug by the retreating Germans, if they were

in a favorable location, and relatively clean.

Usually these were on the south side of a hedgerow, so were not

in the best of location for us We would try to locate our fox holes or slit trench on the

north side of hedgerows, and usually in a corner of a field for the best

protection.

I

had a good jeep driver, and two guards with me constantly, so I had good

help in the foregoing operation.

My

driver was Ralph Winters, who was a roly-poly young boy from

Pennsylvania, and had been a coal miner before getting into the Army.

Everyone called him “Wimpy” because of his professed love of

the famous Wimpy Hamburgers.

Our

food consisted of the normal C and K rations.

C was 3 cans per day per man of various combinations of food, and

the K was 3 boxes of a variety of concentrated foods, cigarettes, and

toilet tissue, one box designated for each meal.

I always thought that they were pretty good, although others

didn’t. This was utilized

when we were on the move, but each Company had a fully equipped kitchen

truck, which had 4 stoves and ovens mounted in it. When there was a 1

– 2 day break, they prepared hot food and brought it forward in large

containers and fed the troops after dark each night.

Some days it was pretty good, but other days it was horrible, but

it was hot. This was where

the C & K rations came in handy!

During

the course of my duties at night, we often did not get back to our

headquarters until very late, and the food was all gone and the kitchen

closed. So, C or K rations!

So,

my enterprising driver Wimpy and the guards started “liberating”

food from the local area farms: potatoes, apples, turnips and whatever

else could be found. They

also scrounged the kitchens for any “left-overs” of odds and ends.

So now, we had to have some meat, so a few chickens were

occasionally liberated, as well as a coop to keep them in.

Well, we had our own private supply of eggs and chicken to eat.

At times we would find a hog that was willing to sacrifice its

life, so that we could have bacon and ham with our eggs.

Some of these boys were good ole farm boys, and knew how to dress

out a chicken and a hog, and boil the chicken in a pot and we would have

chicken soup or stew. Sometimes

they would luck up on a small supply of lard or fat of some kind –

usually liberated from one of the kitchens, and we would have fried

chicken. Not the best

seasoned in the world, nor sanitary, but when you are hungry, you do not

question these trivialities, nor where it came from.

As

we moved forward each day, we loaded up our chicken coop, and usually

enroute we would find a stray chicken, or liberate one from a farm that

we were passing by as replacements for the ones we consumed.

My crew and I looked like a bunch of Oakies rolling down the

road!

And

as a diversion, being in the follow up of the front lines, and yes, even

to the rear, almost every day we would find a cow that had just been “accidentally

hit” and killed by artillery. My

boys would butcher off a hind leg, dress it, and we would have steak!

Not exactly able to cut it with your fork, but it was tasty to

us, and a change, and better than some of the regular rations.

Needless

to say, we did not have to worry about liquids to drink with our meals,

as I became a pretty good scrounger, and found many bottles and barrels

of wine and Calvados, a very famous and potent drink of Normandy, in the

cellars of the farm houses we passed that were unoccupied – bombed or

shelled out! Some of it was

pretty good, and some was rot-gut.

We soon learned that this latter was “green” un-aged wine and

not fit to drink.

Still

we needed to be very careful in our liberating and scrounging, as the

Germans were very adept at booby-trapping anything that was left behind,

and could not be taken with them. This

would involve attaching a very fine wire to the item and concealing the

wire, which would lead 2-5 feet away, and attached to a personnel mine

or other type of explosive. When

the article was disturbed or moved, the wire would release the firing

mechanism of the mine. Frequently severe accidents happened this way.

The Germans knew that we were great souvenir hunters and

scroungers, so, much material and equipment, and even dead bodies were

booby-trapped.

We

all had sufficient training in this so that these accidents should not

have happened, but some were in a hurry and got careless.

Needless to say they paid a steep price for their folly.

Usually

anything that was suspect of being bobby-trapped, was left alone and the

Engineers were notified of its location.

This was one of their jobs, in which they had a great deal of

expertise in de-activating these booby-traps.

From

the very beginning, a very important factor was sanitation, and at each

stop of a day or more, a large slit trench was dug, and surrounded by a

canvas “privacy” shield. A

series of forked cut off branches were implanted in the ground near the

edge, and then a long sturdy branch was laid in the forks, making a seat

for a latrine (out-door toilet). After

a day it began to become mellow, and lime was continually sprinkled in

it, but the methane gas continued to permeate the trench. So, with all of the paper in the trench, it was common to

drop a match into it, when one of our “prima-donnas” were resting,

causing a mild explosion and fire. There was a quick evacuation!! We had to get our fun wherever we could get it…

We,

being the combat liberators of all that was good, we had a very

possessive spirit, and somewhat selfish motives too.

Upon evacuating any comfortable quarters that we had embellished,

we usually said “good-bye” to it by tossing in a grenade.

Also, all barrels and cases of bottled wine and Calvados that we

could not move, were delivered a coup de grace with an axe.

This was done so that the men in the rear echelons would not fall

victim to the frailties of mankind and get drunk, and thereby be unable

to execute their administrative duties.

Also since we had an ample supply of the “stuff”, we could

use it as barter material for some good food supplies and cigarettes, of

which they seemed to have in more than ample supply.

Another

important item was bathing and laundry.

For the most part, our daily personal washing was done in our

helmet: brushing teeth, shaving, bathing – such as it was – and we

did some light laundry in it too – socks, handkerchiefs and underwear.

All of this was pretty primitive, but water was at a premium and

we were only able to get a limited amount each day for “drinking

purposes only”. So thanks

to the liberated wine that we had to drink, we could use the water for

washing!

Periodically

about every 2 – 3 weeks, the Engineers would establish a shower point.

At this time, most all of the men were slowly rotated back for a

shower (cold of course), and got a complete new set of clothing.

This was a great day, as after 2 – 3 weeks of no bathing nor

change of clothing, some were smelling pretty “ripe”.

Later

on in August and thereafter, we became more adventuresome and willing to

take more risks and we started staying in abandoned farm houses, and

some houses in town, usually sleeping in the cellar for best protection.

As we moved along during the “rat- race”, we became more

selective and picked out some better “chateau’s” to stay in for a

day or two.

Once

we got over into Germany, it was no problem requisitioning any house and

to evict its tenants. So here we were finally, comfortable, and sleeping in beds!

We

were the conquerors, so “To the Victors Go the Spoils”, and the

Germans understood this, and were quite cooperative.

What else could they do?

Our

Division’s next assignment was a long move down to Mortain, to relieve

the 1st Infantry Division, which in turn was to join up with

Patton’s Third Army and go to Brest, for the attack and further

operations there.

While

enroute to Mortain, we were still in frontal contact with the enemy,

although they were conducting a rapid retreat and redeployment.

During this advance, I was in contact with an armored unit

attached to us, and near the front of the column of tanks conversing

with the tank commander and getting an assessment of the situation at

hand. All of a sudden, the

lead tank, beside which I was standing, was hit by a German 88mm

artillery shell. It was not

expected and was quite a surprise, but still it was part of the delaying

tactics of the Germans. The

shell hit directly on the nose of the tank, and shrapnel flew in all

directions. I was struck in

the face by a large number of fine splinters of steel – almost like a

stubble of a beard. Only

one small sliver was imbedded deeply in my lower cheek, and since it

didn’t hurt, the medics declined to remove it, as it would have

required surgery. It is

still in there today and causes no pain or problem. It only causes concern and questions to my dental technician

when X-rays of my teeth are made, and the small piece of shrapnel shows

up. Something new to them!!

Our

Division fully replaced the 1st Infantry Division by 8 PM on

the evening of 6 August, on a relatively quiet front – allegedly. The

2nd Bn. of the 120th Regiment occupied positions

up on Hill 314, just east of Mortain, and was in a great defensive

position. Around midnight,

German activity started moving to the front, and 3 Panzer (Armored)

Divisions, with attached infantry, attacked Hill 314.

This hill was a very

prominent point in the terrain, and most important for purposes of

observation. He who held

this hill, had control of the road network for a 20 mile radius.

The Germans wanted and needed this hill, at any cost, for their

plan to break through to Avranches, to be a success.

It

was my job to keep communications flowing from the Regimental Hq. back

to Division Hq., keeping them fully appraised of the activities and

situation on the front lines. This

was a precarious job, as I could carry no maps, no written messages or

anything that could be of value to the Germans in case I were to be

captured.

The

Germans had already captured our 2nd Bn, Hq. and taken most

of the Battalion staff prisoners, including the C.O., along with many

more of the area defenders and medics.

They had broken through our lines in many places.

This made travelling very difficult, as during the course of this

6 day battle, one never knew just which roads were accessible or not.

Mostly we had to use small dirt trails, unusable by heavy

vehicles or tanks, but even then some of these trails were under the

control of the Germans, so alternate routes had to be found.

Our

120th Regimental Hq. was nearly over run on two occasions,

and they had to hastily displace to the rear on very short notice.

To where, no one seemed to know, so this was one of my duties –

to find them wherever they may be.

Fun, fun! At this point, we were occupying substantially well

constructed stone farm houses as headquarters, using the cellars for

adequate protection from artillery and bombing.

At

this point, our Division HQ. was situated in a very nice rural chateau,

named La Bazoge, with 25-30 rooms in it.

All of the Division offices were located in the cellar areas.

I had a small room here as my “home”, which had been a former

coal bin – such luxury!!

This

concluded the Battle of Normandy, officially named the “Normandy

Campaign”.

After

the Battle of Mortain, we started moving eastward on what we called the

“rat race”. We would move 25-50 miles in a day, just keeping the

Germans on the run. As we

moved forward, it was most difficult to keep up with the location of the

Regimental HQ., reporting this back to Division HQ., then racing forward

again to locate the new location of the Regimental HQ. etc. Each trip, reporting the progress and location of the front

lines, thus enabling the Division HQ. to assess their progress and make

plans for the next day’s advance.

Throughout

this rat-race across Northern France and Belgium, we moved as much as

125 miles in one single day, the furtherest advance ever made by any

unit in history of warfare! In doing this, we out ran our supplies of all kinds,

particularly gasoline and ammunition, which could not be brought forward

fast enough. Consequently,

many vehicles were left along the side of the road, only to be retrieved

much later, and ammunition was actually rationed!!

Can you imagine fighting a war and being limited to firing three

artillery rounds per gun per day, or ten rifle bullets per day??

So it was for several days.

Fortunately, since we were in rapid pursuit, there was not much

time for actual fighting, and we by-passed many small pockets of the

enemy left behind for delaying tactics and were known as “snipers”.

They would harass and fire on any targets of opportunity whenever

they could to slow down the advance of our troops, particularly the rear

echelons.

One

particular incident relating to snipers comes to mind.

One of my colleagues, Lt. Harrison Swilley, a big guy from Texas,

was the Liaison Officer from the 823rd Tank Destroyer

Battalion. He drove a

Harley-Davidson motorcycle in his line of duty. One day as he was

returning to the Division Hq., the

urge of nature caught up with him, so he pulled off the road and stepped

into the edge of the woods. Yes,

he still had a little modesty left.

His uniform consisted of a heavy jacket and tanker’s overalls.

All of this had to come off and beneath this was heavy underwear

(long-johns), with a slit in the seat to facilitate relieving one’s

self when necessary. At

some time during his “relief” a sniper spotted him, took aim and

shot at him, striking him squarely in the fleshy part of his buttocks.

He was startled to say the least, grabbed his jacket, pulled up

his overalls and jumped on his bike.

Shortly he came speeding into the Division Hq., screaming,

“I’ve been hit, I’ve been hit, where’s a Medic?”

Upon learning the story, we all broke up laughing about it.

Thankfully it was only a minor flesh wound, and not serious, but

just the circumstances of this incident made it funny.

He was awarded the Purple Heart Medal for this, as it was a

combat wound. I always wondered just how the citation read??

This “rat race” continued on through August, which was called

the “Northern France” Campaign.

On

the 2nd of September we crossed the border into Belgium and

thereby became the first Allied troops to enter Belgium.

We continued on the “rat race” and on 12 September 1944, we

crossed the border into The Netherlands and again became the first

Allied troops to enter The Netherlands, and then we began to run into

stiffer opposition as we approached the Seigfreid Line on the German

border.

From

here we continued our attack through the Seigfreid Line, took part in

the capture of Aachen, the very first city in Germany to be captured in

WWII. Then we proceeded to

cross the Roer River, which was a tremendous and long drawn out

operation. This was by now

mid December, and this became known as the “Rhineland” Campaign.

In

mid December we were called upon to participate in the German

breakthrough in the Ardennes forest/mountains, and took up

positions near Malmedy Belgium until 1 February 1945, when the

former lines of the breakthrough were re-established.

This was one of the most bitter campaigns that we participated in

due to the extreme cold, deep snow and mountainous terrain. We actually

had more casualties due to frost bite, than actual

battle related casualties. This was known as the

“Ardennes-Alsace” Campaign, commonly called “The Battle of the

Bulge”.

After

the Battle of the Bulge, we went back to the area that we had left in

mid December in Germany, continued a rapid advance across

northern Germany, encircling the Ruhr Valley area, then crossed

the Rhine River on 24-25 March 1945.

Then we continued on to Brunswick and finally to Magdeburg on the

Elbe River where we remained until the end of the war on 8 May 1945.

From February through May we were involved in the “Central

Europe” Campaign.

As

for my duties, they continued along just about the same until the end of

the war on 8 May 1945.

After

2½ months of Occupation duty in Germany, we were alerted to return to

the States, undergo intensive jungle training and some amphibious

training, to prepare us for engagement in the Pacific Theater.

While

in England, being en route to the States, the atomic bomb was dropped,

and soon thereafter the war in the Pacific Theater was ended.

We

returned back to the States and were assigned to Ft. Jackson, S.C.

Since the war was now over, it was decided that our Division was

no longer needed, and it was deactivated on 25 November 1945.

This

was the end of the active 30th Infantry Division.

Upon

the demise of the 30th Infantry Division, I was then

reassigned to V Corps HQ., which was then also stationed at Ft. Jackson,

S.C., as the HQ. Co. Supply Officer, a position that I held for about 3

months. Then I became the

HQ. Co. Commanding Officer, (they must have been desperate), and I

remained in that position for 3 more months.

We

were then given choices of new assignments: Hawaii, Philippines,

Caribbean, U.S. or Europe, and I signed up for reassignment in that

order. What did I get?

Europe of course!!

So,

in May 1946, I went back to Europe, and not knowing just what my

assignment would be, I had two intermittent temporary assignments before

I was assigned to the Frankfort Post Exchange, in Frankfort, Germany, as

the Assistant Post Exchange Officer.

In

November 1946, Mary, as a dependent, was allowed to join me there, and

we settled into a small but comfortable apartment.

We were assigned a maid, so this made life a bit easier.

My

duties here were keeping all of the PX installations under our control,

supplied with merchandise. Under

our control were: 21 Post Exchanges in Frankfort and surrounding areas

within a 30 mile radius, along with a camera/watch shop, shoe repair

facility, clothing store, laundry facilities and all other necessary

facilities for day to day life for the accommodation of the thousands of

troops on occupational duty, along with hundreds of nit-picking and rank

crazy dependent wives. We

controlled most everything except the Commissary, the grocery store,

which was controlled by the U.S. Army Quartermaster.

It

was quite difficult in many instances to keep close control on the many

items handled due to the fluctuation in numbers of troops and their

dependents, and their brand choices. Most items had to be ordered 4 – 6 months in advance from

Stateside, and this took time. We

caught “hell” if the supply of Phillip Morris cigarettes ran out.

General “Blank” could not exist without them!

And, his wife had to have first choice on all new merchandise

that came in. You never ran

out of an item more than once!!

Soon

Mary’s pregnancy set in, not by surprise, and the birth time arrived.

Mary delivered a set of twin girls at the 97th General

Hospital, and we were assigned to larger quarters, a two floor

apartment, and two maids. Because

of my job, I had a chauffeur. Officers

could not drive! So, we

were riding high on the hog, so as to speak.

After

another year, Mary delivered us a son, also in the 97th

General Hospital.

After 2 years of this,

the Army decided to down size and to convert the PX system to a civilian

operation. The choices were

simple. Remain in the Army,

and take your chances on reassignment – anywhere in the world that the

Army wanted to reassign you to, or,

remain in current position, if qualified, as a Civilian.

The big deciding factor at the time was salary.

Remain in the Army as a lowly 1st Lieutenant, at a

nominal salary of about $2,500 annually, or, resign and take a civilian

position, doing exactly the same thing at exactly double the salary! Was

there any choice to be made? Of

course not. Resign my

commission, accept a promotion to Captain in the U.S. Reserves, and be

reassigned to my same job at double the salary.

Of course. We needed

the extra money with 3 more mouths to feed, the extra money came in

handy. And the living was

good.

Then

after some more time, we decided that since my contract was running out,

we would return to the States and get back on track of a normal life.

So,

in mid 1949, we returned to the U.S.A.

In

the course of my military service, I was awarded the Bronze Star Medal,

Purple Heart Medal w/Oak Leaf Cluster, Combat Infantryman’s Badge, a

Presidential Unit Citation, a Meritorious Unit Citation, Belgian

Fourragere, and the WWII Victory

Medal and the WWII Occupation Medal, along with the American Defense

Medal, the American Campaign Medal,

and the E.T.O. Campaign Medal

w/5 battle stars.

This

ended my military career.

Frank

W. Towers

March 1998

|

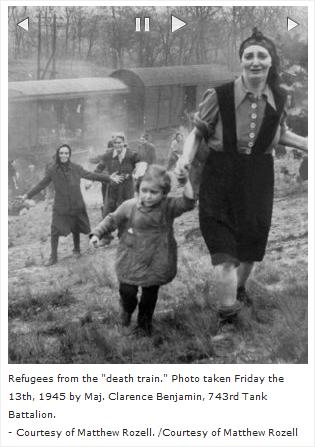

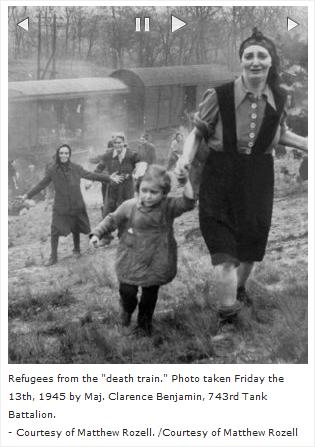

Survivors and liberators reunite at living

history symposium

Jewish Tribune -

Toronto,Canada

Written by Rona Arato |

| Tuesday, 03

November 2009 |

|

The night I met my husband Paul, he told me

that he was in the same ‘camp’ as Anne Frank. My mind flashed to

the bucolic blues and greens of the summer camp I had attended

before fading to the blacks and grays of a Nazi concentration

camp.

Recently, 64 years after liberation from a

death train outside of Bergen Belsen concentration camp, Paul

met the soldiers of the 30th division of the US 9th Army who

freed him. The event was a three-day symposium at Hudson Falls

High School in upstate New York.

Hudson Falls, a tiny village in the Adirondack Mountains near

Lake George, is an unlikely setting for a historic Holocaust

event. Matt Rozell, a history teacher at the high school,

believes that history should be approached as a living organism.

Five years ago he started the Living History project in which he

set out to interview World War II veterans in his community.

When he interviewed Judge Carol Walsh, the former tank commander

recounted how his division stormed Omaha Beach and fought its

way through France, Belgium and into Germany. At the end of the

two-hour session, his grandson Sean said, “Grandpa, you didn’t

tell Mr. Rozell about the train.”

“Ah yes, the train,” said Judge Walsh and launched into this

story.

On April 13, 1945, as his tank descended a dirt road into a

clearing in the Black Forest, he and his tank mate George Gross

came upon a train of boxcars sitting motionless on a nearby

track. Closer inspection revealed the train was filled with

about 2,500 inmates from the Bergen Belsen concentration camp.

Their German guards had fled the advancing Allies, leaving the

prisoners locked in sweltering box cars without food, water or

sanitation facilities. A few people had left the front three

passenger cars and were milling about, looking for food. One of

them spoke English and told the soldiers their story.

Walsh and Gross radioed back to their battalion for help and a

short time later, their commander, Frank Towers, a

27-year-old first lieutenant joined them. As the soldiers opened

the boxcar doors they were stunned by dead bodies falling on top

of them. The people inside, many of them children, were filthy,

sick and starving. By that time, they had been in the cars for

four days and the stench was unbearable. The soldiers helped the

survivors from the train and gave them whatever food they had

with them.

“We were shocked,” said Walsh, who was 24 at the time. “We

didn’t know what to do with all these people.”

Shocked, but not helpless. Walsh was told to move on, so his

tank-mate Gross spent the night guarding the survivors in case

the German guards should come back. Towers returned to his unit.

The next day, he and the men of the 30th division arrived with

trucks, food and medical aid.

The survivors were taken to the nearby town of Hillerslaben

where they were assembled in the town square, stripped, sprayed

with DDT and their lice-infested clothing burned.

Towers ordered the German

inhabitants to open their homes and provide food, clean clothes

and sleeping quarters. The sick, including Paul’s mother Lenke

who was suffering from typhus, were taken to the hospital where

they received medical treatment.

Rozell posted this story on his

‘Teaching History Matters’ web site. It was picked up by The

Associated Press. Soon train survivors from around the world,

including Paul, read it and contacted him. In late September,

survivors, rescuers, family members, teachers and students

gathered in the Hudson Falls High School auditorium.

We were joined by historians from the Bergen Belsen Memorial,

The National Holocaust Museum in Washington, DC and others

interested in study of the Holocaust. We all wore green

wristbands with white lettering that said: ‘Remember the

Holocaust; end prejudice and hatred.’

When Paul met his liberator, Walsh, now 87, he said “give me a

hug; you saved my life.” As the men embraced I cried.

Like the other train survivors, Paul had spent 64 years longing

to meet and thank the men who liberated him. He had searched the

annals of Holocaust literature for mention of the train. It

wasn’t anywhere. No one seemed to know it had existed.

We now know that this was one of three trains that left Bergen

Belsen in the last days of the war. The Germans felt that if

they emptied the camp of prisoners, no one would know what they

had done.

We believe that one train went to Treblinka where everyone was

killed and that prisoners on the second train were executed by

their guards. Paul’s train was headed for the same fate when the

approaching Allied armies scared the guards away.

The symposium lasted three days. During that time we talked,

listened, cried, laughed and applauded the courage of the

soldiers, and of the survivors who, despite the horrors they

endured, have lived meaningful, productive lives.

Survivors exchanged stories, validating each others’ memories.

Each gave testimony to the students who then swamped them with

the kind of adulation usually reserved for rock stars.

The soldiers also spoke of their experiences. Among them was

Francis Curry, the last surviving World War II Congressional

Medal of Honor recipient from New York State.

“We were just doing our job,” said Frank

Towers, in response to the survivors’ heartfelt thanks.

When Judge Walsh addressed the audience he told the survivors,

“You don’t owe us anything. We owe you – for standing by and

allowing this terrible thing to happen to you.” To the students

he stressed vigilance against hate and prejudice in all forms.

They responded with a standing ovation.

We came away from the symposium with glowing memories, new

friends and a renewed sense of hope and commitment. To date

about 65 train survivors, five from Toronto, have contacted Matt

Rozell.

Commenting on the soldiers’ actions, Paul said, “they went way

beyond their job. What other army in the world would have

stopped fighting and refused to budge until they made sure that

a starving, ragged group like us was cared for?”

The symposium concluded on Friday night Sept. 25 with a farewell

dinner during which we all watched as Rozell, his students, the

soldiers and survivors were declared “Person of the Week,” by

Diane Sawyer on ABC News. “Now that the project has received

worldwide coverage, Rozell hopes to hear from more people who

were on the train.

On Saturday, Sept. 26, Matt Rozell and his family drove to

Corning, NY, where he was honored as DAR (Daughters of the

American Revolution) Outstanding Teacher of American History

2009.

|

A few days before Christmas, 89-year-old World War II

veteran Grier Taylor of Batesburg-Leesville got an

unexpected telephone call. The woman on the other end

of the line spoke halting English, but her message was

clear: She wanted to thank Taylor for helping to save

her father’s life.

Her father, now a physician in Israel, was a

14-year-old boy on April 13, 1945 – one of about 2,500

filthy, starving prisoners of Germany’s infamous

Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. The suffering souls –

700 of them children – had been packed into boxcars in a

veritable death train. They were bound for an uncertain

future in another camp farther away from the front lines

when they were liberated by advancing American troops.

Sixty-some odd years after he was a

litter bearer carrying the dead and

dying from a death train liberated

by US troops in World War II, Grier

Taylor of Batesburg-Leesville got a

call from Israel. It was a daughter

of one of the victims, thanking him

for his service. "Without you, I

would not be here," said the woman.

-

TIM

DOMINICK /tdominick@thestate.com

“She said, ‘Merry Christmas.’ I said, ‘Happy Hanukkah,’”

said Taylor, sitting at the dining room table of his

tidy home on Lake Murray. “I thought it might be a prank

call. But then she started talking about my unit, and I

knew she was real. It was just a shock.” The call was

just the latest chapter in an almost decade-long effort

by Varda Weisskopf and others to learn more about the

“death train” and the U.S. soldiers who liberated it.

Her path to Taylor covered a decade and ran though an

Upstate New York high school website, a retired soldier

in Florida and, finally, one of Taylor’s Army buddies.

“I told him that I salute him for having left his

family and gone to Europe to liberate the continent from

the yoke of Nazi occupation,” Weisskopf wrote The State

in an email from her home in Rehovot, Israel. “I called

to thank him and told him about the story of the train.

And I told him also that I extend to him my most

heartfelt appreciation for helping to save my father.”

‘60,000 alive and mountains of

corpses’

During the war, Weisskopf’s grandparents and father,

Mordechai, were rounded up by the Nazis in Budapest,

Hungary. In 1944, Mordechai was separated from his

parents and taken to the Bergen-Belsen concentration

camp in northwestern Germany.

Bergen-Belsen had originally been a prisoner of war

camp – Stalag 11-C – for Russian soldiers. But in 1943

it was converted to house “elite” Jews from around

Europe. They were to be used as bargaining chips to

exchange for German prisoners and for other purposes,

said Matthew Rozell, a high school history teacher from

Hudson Falls, N.Y., who began doing oral histories of

World War II veterans as a class project in the early

1990s. It was his class website –

teachinghistorymatters.wordpress.com – that helped Varda

Weisskopf on her search.

As the war progressed and the Russians began moving

forward on the Eastern Front, the Nazis transferred more

and more prisoners from camps in the east to

Bergen-Belsen.

By 1945, “it was huge, massive,” Rozell said of the

camp. “When it was liberated on April 15 by the British,

they found 60,000 (people) alive and mountains of

corpses. Literally mountains.”

Some estimates put the number of dead at the end of

the war at 50,000. Still, Bergen-Belsen wasn’t

considered a death camp like Auschwitz in Poland.

“They didn’t have gas chambers,” Rozell said, “but

they had crematoriums because people were dropping like

flies from starvation and disease.”

Six days in locked boxcars

Bergen-Belsen was located in the northwestern German

province of Lower Saxony, near the town of Belsen.

As the war neared its end and the Third Reich was

collapsing – with the British and Americans driving east

across Germany and the Soviets closing in from the west

– the Nazi regime decided to relocate many of the

prisoners to a camp in Czechoslovakia. They were loaded

into three trains – about 1,700 to 2,500 per train. It

was a nerve-wracking experience for the prisoners.

“These people didn’t know where they were going,”

Rozell said. “It was never a good idea to get on a train

to places unknown.”

One train made it to the Czech camp at Theresienstadt.

Another was liberated by the Russians.

But a third train – the one on which Mordechai

Weisskopf rode – was stopped en route near the town of

Farsleben, Germany, southwest of Berlin. The tracks had

been bombed by the Allies, impeding the Germans’ retreat

to the east.

There, the prisoners waited for six days and seven

nights, packed shoulder to shoulder in locked boxcars,

with little or no food and a single bucket as a toilet.

They were part of what Rozell called “the greatest

crime in the history of the world – the Holocaust.”

Liberation for some, too late

for others

On April 13, 1945 – Friday the 13th – some tanks

rolled in and the Nazi guards ran away. It was a lucky

day for some, as tattered, emaciated and utterly

thankful people poured out of the cars and tried to

embrace the American soldiers.

But for many others, it was simply too late. They had

died in the car, and others would die in the coming

days.

The American tankers were a reconnaissance element of

the 743rd tank battalion. The battalion was attached to

the 30th Infantry Division of the U.S. Army – the Old

Hickory Division formed at Fort Jackson from soldiers

recruited or drafted from the Carolinas and Tennessee.

Lt. Frank Towers was a headquarters liaison officer

with the 30th Division. He saw the train first-hand and

through the years penned a 32-page paper chronicling

“The Death Train at Farsleben, Germany.”

“We had seen our own men killed and maimed, torn

apart. We expected that. That was part of war,” said

Towers, now of Gainesville, Fla. and the 30th Division’s

historian. “But when we saw these people – walking

skeletons, dirty, stinking, infested with lice and fleas

– we didn’t want to get close to them. We didn’t know

what kind of diseases they had. It was a miserable lot

of people. They fell out (of the boxcars) like

cordwood.”

The tankers – among them George Gross, who passed

away in 2009, and Carrol “Red” Walsh, still living, who

Rozell had interviewed for his class – had to move on

the next day.

“We were fighting a war, not babysitting people,”

Towers said.

So Towers got the job of finding transportation to

take the survivors to a former Luftwaffe (German Air

Force) hospital near Hillersleben, Germany. It was an

18-mile circuitous route because most of the bridges in

the area had been bombed by the Allies or blown up by

retreating German troops.

That’s when Taylor’s story begins.

‘The most horrible sight and

smell I have ever seen’

Taylor was drafted in 1942 when he turned 21 years

old. At the time, he was living in West Columbia.

He went through basic training and eventually became

a litter (stretcher)-bearer with the 95th Medical

Battalion.

The men of the 95th were trained to treat soldier for

injuries suffered by poisonous gas. But by the time they

reached Omaha Beach in Normandy 30 days after the D-Day

invasion, it was apparent that poisonous gas – so deadly

in World War I – would not be used in World War II.

So the 95th became a regular medical battalion,

setting up aid stations behind Gen. George Patton’s

Third Army as it raced across France. Taylor’s main job

was to poke through bombed out buildings, looking for

wounded soldiers or dead bodies, and then haul them back

to the aid station for treatment or burial.

The 95th worked its way across France and Belgium,

and then hooked up with the Ninth Army as it drove

through Germany. It found itself in the wake of the 30th

Infantry Division, operating the hospital in

Hillersleben when the death train refugees started

pouring in.

“When we took them off the trucks, we didn’t know if

they were dead or alive,” Taylor said. “We had a tent

set up in the yard for a morgue. We took their pulse and

either took them to the morgue or set them up in the

hospital.

“They had all urinated and (defecated) on themselves

for so long. I was sick at my stomach, close to

vomiting. It was the most horrible sight and smell I

have ever seen, and I hope to God I never have to see

that again.”

‘I was touching history’

Flash forward to 2005.

Towers met a survivor of the train living in Florida

– Ernest Kan. He also began penning his remembrances of

the incident. And then Kan came across Rozell’s website.

Rozell and Towers began collaborating, locating other

survivors and liberators, attempting to unite them.

Mordechai Weisskopf in Rehovot, Israel, saw Rozell’s

website and called Towers to thank him. But because

Mordechai wasn’t fluent in English, he handed the

telephone to his daughter, Varda.

“It was a shock to me,” Varda Weisskopf said. “Two

days I did nothing; I just thought about it. I felt like

I was touching history to talk to the American soldier

who saved my father’s life.”

She then joined Rozell, Towers and others in locating

survivors and liberators and bringing them together. She

even hosted a reunion in Israel last April.

Through Rozell and Towers, Weisskopf located one of

Taylor’s Army buddies – Walt “The Babe” Gantz of

Scranton, Pa., and he told her about Taylor and two

others who served in the 95th – Bob Shatzof Upstate New

York and Fred Nicoletti of New Hampshire.

Weisskopf called them all.

“Immediately, I wanted to call him,” she said of

Taylor. “I felt it is my duty to talk with every soldier

who was there, to thank them.”

Taylor finds that remarkable.

“Her crusade is beyond what I have words to explain,”

he said.

The phone call brightened his Christmas.

Taylor stresses that he played a minor part in the

death train story, and in the war, for that matter.

“I didn’t do all of that myself, you know,” he said,

laughing. “I did have a little help winning that war.”

And as for those who say there wasn’t a Holocaust?

“I was there and I saw it,” Taylor said. “It was just

pure hate, and I pray that we never reach anything close

to it again.”

Video excerpts from reporter Jeff Wilkinson’s

interview with World War II vet Grier Taylor

click

here for the interview

(Slow to load) Reach

Wilkinson at (803) 771-8495.

The State, South Carolina's Homepage

|

Soldiers, survivors converge in Louisville

April 19, 2013

By ALAN SMASON, Exclusive to the CCJN

Frank Towers remembers the day through the haze of 68 years,

a footnote at the end of World War II. Matt Rozell was never

there, but through his efforts and those of his students, he can

dictate with amazing accuracy what happened in Farsleben,

Germany those many years ago. Yet to the five Holocaust

survivors who met with Towers and Rozell at a World War II

reunion this past weekend in Louisville, KY, it was a day they

will never forget. It was the day American forces gave them

something they thought they would never see again: freedom!

30th Division U.S. Army Infantry Veterans executive

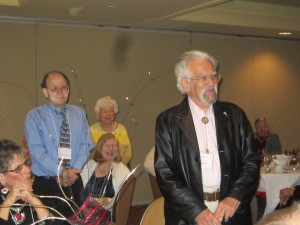

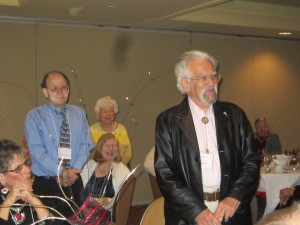

secretary Frank Towers, center, welcomes Gideon Kornblum,

left, and Kurt Bronner. (Photo by Alan Smason)

At 95 years, Towers is the last of the 30th Division of the

United States Army Infantry members who can say he was there and

had personal contact with this almost forgotten chapter of

history. His testimony shows he was assigned the duty of dealing

with what the Nazis regarded as human refuge on April 14, the

day after the survivors, crammed into tiny freight cars,

starving and in some cases dying, had been freed from their

captors by members of the Tank Destroyer Batallion 743 assigned

to Tower’s 30th Division named for Andrew Jackson and fondly

referred to as “Old Hickory.”

Rozell, a high school teacher in Hudson Falls, NY, is the

conduit by which Towers and the remaining 30th Division members

have connected to the Holocaust survivors, all now septgenarians

or octogenarians, from the first of three trains sent out from

Bergen-Belsen concentration camp on April 6. It is through his “Teaching

History Matters” website set up decades ago and fueled as

part of his commitment to teaching his students the lessons of

World War II that he has become heralded as an authority on an

event that took place years before he was born.

Hudson Falls High School teacher Matt Rozell addresses the

crowd of veterans and survivors. (Photo by Alan Smason)

It is through his efforts and the resources he and his

students have placed on the Internet that reunions where

veterans can meet with survivors have been possible. More than

200 survivors of what Towers calls “the death train” have been

identified and contacted through Rozell’s networking efforts.

The five survivors who traveled to Louisville to spend time

with their families touring the Louisville Slugger plant and

other city sites are part of a vast network of Holocaust train

survivors now living throughout the United States, Canada,

Israel, Europe and as far away as Australia. The manifest of the

names of all those loaded on the train is now listed on Rozell’s

site and linked with the United States Holocaust Museum and Yad

Vashem in Jerusalem.

This year two train survivors, Ariel University emeritus math

professor Gideon Kornblum from Jerusalem and retired graphics

printer Kurt Bronner from Los Angeles, were new to the

gathering. They joined with retired Duke University medical

professor Dr. George Somjen from Durham, NC; Brooklyn College

physics professor Micha Tomkiewicz from Brooklyn, NY; and Bruria

Bodek Falik from Woodstock, NY, all of whom have attended

reunions with the remaining veterans beginning in 2008 and

continuing ever since.

Bergen-Belsen concentration camp survivors (from left) Micha

Tomkiewicz, Bruria Falik and Kurt Bronner. (Photo by Alan

Smason)

In every case these Holocaust survivors brought their wives,

children and grandchildren with them to meet and socialize with

the children and grandchildren of the men they consider the

liberators of their families.

This year only 12 veterans were in attendance. Their number

was lessened in December with the passing away in Florida of

Carrol Walsh, a retired New York State Supreme Court judge, who

was one of the two tank commanders that captured the train in

question.

It was through Walsh’s grandson, a student in Rozell’s

history class more than a decade ago, that Rozell first learned

of what occurred on that date. Beginning in 2001, he heard

first-hand in a series of interviews with Walsh how he and

fellow tank commander George Gross happened onto the train and

its human cargo.

Rozell explained how the train got there. On April 6 the

Bergen-Belsen commander, fearing the approach of the Soviet Army

and not wanting to let the world know of the savagery of the

Third Reich and its “Final Solution,” dispatched three separate

trains crammed full with prisoners to Theresienstadt

concentration camp, also known by the name of its garrison city,

Terezin. Of the three trains sent out that date, the first with

2,500 aboard encountered a series of mishaps that made it fall

into the hands of the Americans on April 13. A second train with

1,700 prisoners aboard, using information it gleaned from the

first train, eventually made it to Terezin on April 20, where

most of its inhabitants were liberated on May 8 by the Soviet

Army. The third train with 2,400 souls aboard also was liberated

by Soviet troops on April 23 at Trobitz.

With laser pointer in hand, former 1st Lt. Frank Towers

prepares to show audience members where the train was

liberated at Farsleben. (Photo by Alan Smason)

Walsh and Gross were on a scouting mission along with members

of the 119th regiment, having been dispatched from the recently

captured town of Hillersleben by Major Clarence Benjamin.

Benjamin had come upon several Jews who had escaped the train

while it lay in wait. They had told him of the train’s existence

and he instructed Walsh and Gross to accompany him.

Despite its holding a full head of steam, the train commanded

by SS Captain Hugo Schlegel and its complement of a dozen guards

or SS troops were contemplating orders from the German command.

In front of them were the Allied forces, while behind them the

Soviet troops were advancing. The orders were chilling. Either

blow up the train there with explosives found in one of the

freight cars or advance the train to the Elbe River, blow up a

bridge there and plunge the train into the waters below, killing

all aboard including the guards.

The train was standing at a spot so remote it was originally

considered as Magdeburg by the World War II veterans who first

began to tell their stories. Walsh and Gross saw several Jewish

prisoners milling about, but when they pressed their tanks into

service, the German guards threw their rifles down, ran away or

disrobed, attempting to evade capture by donning the clothes of

their captives. It was in vain, though, because their much

better physical condition gave them away almost immediately.

Emeritus mathematics professor Gideon Kornblum traveled from