|

TOUGH TIME FOR THE `TOUGH HOMBRES'

|

During the bloody fighting in the

bocage, a small group of German paratroopers captured 11 officers and more

than 200 men of the U.S. Army's 90th Infantry Division.

In the weeks following

D-Day, countless bloody battles erupted throughout Normandy as the Germans

tenaciously clung to every square mile of the bocage (hedgerow country)

and sought to exact maximum casualties for each piece of ground yielded. A

seesaw struggle without a clearly defined front, the battle for Normandy

became a series of brutal small actions in which attacks were met by

counterattacks and real estate changed hands on a daily basis. One such

action in July 1944 pitted GIs of the U.S. 90th Infantry

Division, known as the "Tough Hombres," against

counter attacking Germans of the 6th Fallschirmjager (Paratroop) Regiment

under Major Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte. The hard-fought

battle would result in the capture of more than 200 U.S. troops and an

unusual truce between the Germans and Americans to evacuate wounded

soldiers.

The Bavarian-born Major

von der Heydte had already fought in France, Crete, Russia, North Africa

and Italy before he trained and led the 6th Fallschirmjager into battle in

Normandy. A military aristocrat and member of the Luftwaffe (since German

paratroop formations were technically not part of the army), he had

supervised the 6th Regiment's re-formation at the beginning of 1944, and

by May--when the regiment was deployed to France--its members were well

prepared to demonstrate its motto, "Sweat spares blood."

Although they never

parachuted into combat, all of the 6th's troopers had earned their jump

wings, and all had jumped several times during training. While the

commissioned and noncommissioned officers were mostly battlewise and

experienced, the rank and file were generally quite young. Many of them

first saw combat against Allied soldiers in Normandy--and for many it was

also their last. Between June 6 and 10, 1944, the 6th Fallschirmjager's

1st Battalion was wiped out in heavy action.

~~~~~~~~

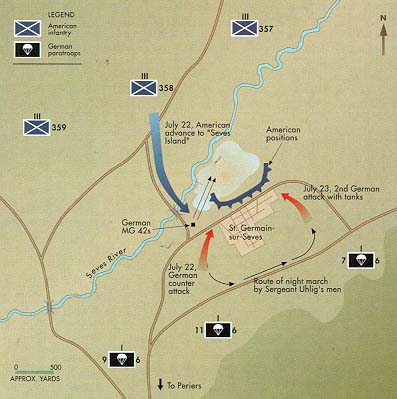

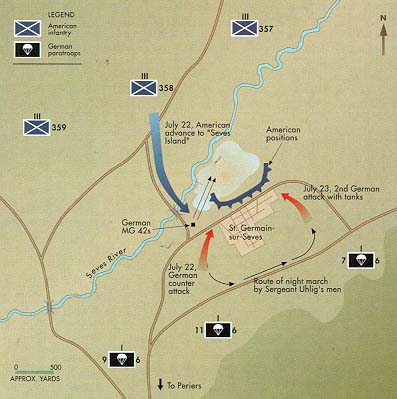

By July 22, elements of

the German regiment's 2nd and 3rd battalions

were entrenched in defensive positions opposite the 90th

Infantry Division on the Cotentin

Peninsula. The 90th had landed at Utah Beach right behind the initial

assault elements. The division fought hard and

lost heavily during the initial battles for Normandy's hedgerow country,

as did many other American units. The 90th's enlisted replacements had

reached more than 100 percent of the division's

authorized strength by July 22. Many of the "veteran combatants" had been

replacements themselves a short time before. Infantry

officer replacements totaled nearly 150 percent.

On July 18, the 90th

began preparations for an assault on the village of St. Germain-sur-Seves

as a prelude to Operation Cobra, the planned attack on St. Lo that it was

hoped would allow Allied ground forces to break out of hedgerow country.

The capture of St. Germain-sur-Seves would put the division

in a position to push forward to the key crossroads town of Periers, then

advance to the highway linking Periers with the important city of

Coutances, located near St. Malo, at the base of the peninsula.

St. Germain-sur-Seves

lay atop a low "island" surrounded by terrain that made it relatively

inaccessible. On the north it was bounded by the Seves River, and on the

other sides it was bordered by swampland and creeks. This rise of earth,

which was itself crisscrossed by hedgerows, was roughly two miles long and

about half a mile wide. In July 1944 it had become even more isolated than

usual from the surrounding territory because of heavy rains that had

fallen during the previous month. For the Americans, this problematic

piece of real estate would become known as Seves Island.

A night attack on St.

Germain-sur-Seves was initially proposed, but the idea was scrapped

because of the high numbers of green replacements in the

division. Instead, Maj. Gen. Eugene M. Landrum, the 90th's

commanding officer, opted for a daylight attack. He selected the 358th

Regiment, commanded by Lt. Col. Christian E. Clarke, Jr., to make the

assault and arranged for heavy fire support for the offensive. As it

happened, fire support was available because the 90th's attack was the

only one planned for that time frame in its sector. Landrum also asked for

close-air support, and he directed his other infantry

units in the area to bolster the attack with fire from their own weapons.

The assault began around

0630 hours on July 22, after a 15-minute artillery barrage intended to

soften up the German defenses. The 358th Regiment's 1st and 2nd battalions

advanced toward St. Germain-sur-Seves from the north, along a road that

crossed the Seves River. The narrow road had connected the surrounding

countryside to the western tip of the island via a bridge, but the Germans

had destroyed the span before the battle. According to the plan, the two

battalions were to create a bridgehead so that engineers could come in and

construct a temporary bridge that would allow tanks to cross the swampland

to the village.

Initially the attack was

successful. The artillery support was so massive that it compensated for

poor visibility that had precluded an airstrike on the island and kept

observation aircraft from directing artillery fire. The 358th's 1st

Battalion breached the forward positions of the 3rd

Battalion of the 6th Fallschirmfager, penetrating more than a quarter mile

inside the German lines. But since there was little cover available in the

swampy terrain, the advancing Americans exposed their flank. In spite of

the artillery support, U.S. casualties were heavy. Two officers and seven

men were killed, and 10 officers and 180 men were wounded.

At about 1200 on the

22nd, Major von der Heydte gave orders to drive the American troops from

the island and throw them back across the river. Since the German

commander apparently believed that the Americans who had come across

constituted a small reconnaissance force, he sent only Company 16, led by

Sergeant Alexander Uhlig, to mount a counterattack. Von der Heydte ordered

Uhlig to push the Americans back and re-establish the old main line of

resistance along the river, adding that, if possible, he was also to

capture a couple of prisoners for questioning.

Uhlig, whose company was

down to 32 effective members by that point, briefed his men and sent them

off to take up their position for the attack. Although the members of

Company 16 were lightly armed and should have been able to move quickly,

their progress was slow. Visibility had improved by midday, and American

aircraft now controlled the skies, relentlessly attacking the Germans. As

Uhlig's men advanced along a sunken road between two hedgerows, they were

hit by artillery fire that wounded a noncommissioned officer and three

privates. Two other men left the group to escort the wounded to an aid

station. Meanwhile, Uhlig and one of his corporals made a visual

reconnaissance of the contested terrain and discussed what to do.

To Uhlig's front, 800

yards of what had formerly been the German main defensive line was now

held by American troops. To his left was German Company 6, and there was a

gap in the line where Company 11, which had retreated, had formerly been

positioned. Much to Uhlig's dismay, he saw that he was facing more than

300 Americans. Knowing that it would be suicidal to mount a frontal

assault, Uhlig attacked the shallowest part of the U.S. penetration, its

right flank. Uhlig's men crept and crawled steadily forward, using mounds

of earth and hedges for cover. Along the way, the German sergeant assumed

command of some men from another company to reinforce his own

understrength unit.

At about 1800, the

German paratroopers launched their attack against the 358th's 1st

Battalion. During the next three hours the American forces retreated about

350 yards. According to the 358th's intelligence officer, Major William J.

Falvey, the 1st Battalion ended up more than a half mile south of the

river, having been reduced to half strength by casualties and stragglers.

A company of the 2nd Battalion had managed to advance about 150 yards

beyond the Seves and thus was located to the rear of the 1st Battalion.

The Americans had also been able to bring two platoons of tanks across a

temporary bridge.

Although Uhlig's men had

pushed the Americans back and inflicted heavy casualties, they had not yet

captured the prisoners von der Heydte wanted. By now Uhlig's little group

had been reduced to 28 men. Two of the paratroopers who had been slightly

wounded chose to remain with the unit rather than be evacuated.

As the fighting drew to

a close that evening, the Americans knew that they were in a precarious

position. They expected another attack from the same direction. During the

night they struggled to evacuate their wounded, many of whom were lying

among the reeds and long grass on the north side of the river. In the

darkness, some of the inexperienced troops began drifting to the rear.

Major Michael Knouf, the

358th's regimental supply officer, was doing his best to keep supplies and

ammunition coming across the river to the troops in the front-line

positions. B and C companies were the farthest forward of the 1st

Battalion's companies. The 1st and 2nd battalion troops now formed a

horseshoe-shaped line some 200 yards deep and 1,000 yards wide on the

island's high ground. The morning of the 23rd

found Knouf still south of the Seves, trying to push supplies forward.

Meanwhile, on the

evening of the 22nd, Uhlig had reassessed the situation to his front.

Although the American bridgehead had been reduced, he knew his mission was

not yet fully accomplished. The sound of the American troops digging in

led him to conclude that another attack against the same flank would not

succeed, so he decided to launch an assault on the other flank. Figuring

that he would need more than 28 men to overcome the Americans, he went

looking for reinforcements. A tank commander from the nearby 2nd SS

Panzergrenadier Division told Uhlig he would

provide three tanks for the next morning's attack. The 3rd

Battalion promised him two MG 42 heavy machine guns and 16 men. Since the

men he had been promised were replacements, with only limited battle

experience, Uhlig initially planned to use them as a reserve, but he later

decided to employ them in a more active role.

Uhlig knew that the MG

42, which featured a very high rate of fire in the neighborhood of 1,300

rounds per minute, was feared and respected by American troops. He

reasoned that if he could make good use of the two guns promised him, they

could give him an edge in the next day's battle. Uhlig also understood the

importance of terrain in planning an assault, and he saw that control of

the meadowland near the Seves River was critical to the success of his

operation. He wanted to keep reinforcements from reaching the forward

elements of the 358th's 1st Battalion as well as block any American

attempt at withdrawal, to guarantee that he would have some prisoners to

bring back to yon der Heydte.

Uhlig positioned the two

MG 42s so that they could support both those objectives, placing them in a

sunken road northeast of St. Germain-sur-Seves, where the crews could see

the Seves River meadow and have unobstructed fields of fire. He ordered

the gun teams to dig in and camouflage their positions, since Allied

aircraft were constantly overhead, looking for targets. The men used the

remaining hours of darkness to establish their battle positions.

To achieve surprise and

maximize the guns' effectiveness, as well as protect their crews from the

American artillery as much as possible, Uhlig gave strict orders that the

machine-gunners should not fire during the initial assault. He believed

that he might be able to dislodge the enemy troops from the island without

the machine guns and planned to have the MG 42 crews support the action

only if the Americans tried to bring in reinforcements or withdraw.

As it happened, the

cloud cover on the morning of the 23rd was so

low that Allied aircraft were unable to provide effective ground support

for any operation. The Americans still had artillery backup available, but

effective adjustment was difficult because of the terrain and the

proximity of the Germans to the 1st Battalion troops.

South of St.

Germain-sur-Seves three German tanks prepared to link up with the

attacking paratroopers. Uhlig's men waited for the signal to advance. In

his original plan, the sergeant had assigned a combat group of one

noncommissioned officer and six men to accompany each tank during the

assault, so that the tanks could shield the dismounted men. To Uhlig's

consternation, however, the tank commanders rejected that idea because the

terrain provided too little protection against any American anti-tank

screen. If Uhlig wanted armored support, he had no choice but to put his

paratroopers out in front of the panzers and hope that just the presence

of his tanks would have an unsettling effect on American morale. In any

case, Uhlig believed he had no alternative but to go forward.

Shortly after 0700 on

July 23, the German paratroopers--now numbering about 50--left their

trenches. Uhlig's first attack, at 0800, hit the 1st Battalion close to

the unit's command post. Then the Germans were temporarily stopped by fire

from American artillery and tanks.

But the Americans found

it difficult to adjust their artillery fire without observer aircraft. The

German troops later claimed that most of the rounds went over their heads.

As the American forward observers tried to adjust their artillery fire,

bringing it back toward American lines, the 358th's soldiers huddled

deeper in their foxholes. The German paratroopers began moving forward,

how ever, to avoid being hit from the rear. German supporting fire also

caused the GIs to keep their heads down.

Although Uhlig's men

began advancing that morning with the three tanks they had been promised,

two-thirds of their armored support was soon lost. One tank fell behind

because of mechanical problems, while a second tank, which was advancing

through a farmyard, rammed a wall and got stuck in the ruins of a caved-in

tile roof. After that, it was little help to the paratroopers aside from

providing occasional supporting fire.

According to subsequent

American battle reports, the Germans made three attacks that morning. The

first hit at 0700 and the second at 0800 (the U.S. troops were observing

double daylight savings time while the Germans were not, which accounts

for some time discrepancies in after-action reports). The second attack

was aimed between the 358th's 1st and 2nd battalions. The Americans

stopped the second attack as well. A third attack, however, hit the 1st

Battalion head-on and broke through to the battalion's command post. Only

a few GIs responded to that attack by firing their weapons. Most fell

back, panic-stricken, to two fields that bordered the river. Then a German

shell landed in a corner of one of the fields, resulting in many

casualties.

At that point Major

Knouf witnessed the final disintegration of control within the American

units on the island. He was about 30 yards away from the command post,

trying to make sure that supplies were being forwarded to the front, when

he saw the 1st Battalion commander, Lt. Col. Al Seeger, ordering his men

to cease fire. Soon a group of American soldiers started toward Uhlig's

men with their hands up in the air. Knouf decided not to be a party to the

surrender, so he shouted to his men to retreat across the meadow toward

the river.

Sergeant Uhlig's two

heavy machine-gun crews then commenced firing, per their orders. Their

position made it possible for them to wreak havoc on the withdrawing

Americans. The German machine-gun fire dashed any hopes the GIs had of

getting safely to the other side of the meadow. Some U.S. troops did

manage to get through the murderous fire, but many more were killed and

wounded, since there was no cover. Knouf himself was hit and seriously

wounded.

Uhlig had employed his

machine-gunners brilliantly, taking into account their lack of combat

experience and assigning them duties they could accomplish from the

relative safety of well-concealed positions. The Americans, on the other

hand, were at a tremendous disadvantage. The 358th had been taking heavy

casualties ever since it had been committed to fighting in the bocage.

Just days before the battle at St. Germain-sur-Seves, many brand-new

replacements had joined the regiment, and they had not yet been

successfully molded into combat teams. It is probably not surprising that,

when confronted by a German tank accompanying paratroopers, and with their

only escape effectively blocked by fire, many of the green GIs did the

only thing they thought was logical when Colonel Seeger ordered them to

cease firing and surrender. They simply did as they were told.

Uhlig was amazed at his

own success. He figured that his opponents had had no idea how small his

attacking force was. But he probably underestimated the cumulative impact

that his paratroopers--assisted by armored support, strategically

positioned machine guns and misdirected American artillery fire--had had

on the under-strength and weary American infantrymen. The German sergeant

had been able to optimize the impact of his small force because he

understood how to combine his limited assets to the best advantage.

But the story of Seves

Island does not end when the Americans started putting their hands up.

Perhaps the most unusual aspect of the battle--which was, after all, a

minor skirmish in the course of the struggle for the bocage--took place

after the American surrender that day.

Uhlig divided the GIs

into groups of 20-25 soldiers and assigned a paratrooper to escort each

group to the German regimental command post in St. Germain-sur-Seves,

where von der Heydte was waiting for a report. When the sergeant saw that

he was rapidly running out of men to serve as escorts, he realized that he

had captured more than 200 men. Once the captives had been sent on their

way to the rear, he reoccupied the main line of resistance with his

machine-gun crews and men from other nearby units and then returned to the

village with his remaining paratroopers, reporting to von der Heydte that

he had accomplished his mission.

The German major, who

had set up his command post in the loft of a large farmhouse, commended

the sergeant and introduced him to the 11 American officers he had

captured. What happened next might be interpreted as an indication of how

the aristocratic von der Heydte believed vanquished enemies should be

treated. Everyone present at the command post--including the captive

officers--had tea together. It was a moment of civility amid weeks of

mindless, bloody fighting. And the German commander's chivalrous gesture

toward the Americans was to be echoed in additional actions he took later

that same day.

At about 1500, von der

Heydte received a report that several Americans were trying to help the

wounded men lying in the swampy grasslands between the island and the

Seves. Three U.S. Army chaplains attached to the 358th

Infantry--Catholic Father Joseph J. Esser, Salvation Army

Chaplain Edgar H. Stohler and Disciples of Christ Pastor James M.

Hamilton--had decided among themselves to go out into no-man's land to

look for wounded troops. Armed only with small white flags with red

crosses on them, they defied strafing aircraft and fire from both sides as

they made their way out into the marsh grass, searching for soldiers who

could still be helped. When the German troops realized what the chaplains

were doing, they were so impressed with their bravery that they stopped

shooting. The Americans did likewise, except for the artillery well to the

rear.

A paratrooper captain moved forward to greet the

chaplains, who were by then directing litter-bearers to pick up the

wounded men they had located. He and the chaplains conferred with the help

of a German-speaking American, and according to one German account, they

decided to inform von der Heydte of what was taking place. A German

officer later claimed that von der Heydte suggested a truce and an

exchange of wounded prisoners.

It was apparently not the first time yon der

Heydte had acted humanely toward an American unit after a bloody battle.

On July 4, the 6th Fallschirmjager's troops had halted an attack of the

U.S. 83rd Infantry

Division in the same sector, inflicting very

heavy casualties on its 331st Infantry Regiment.

The division lost nearly 1,400 men in its

ill-fated attack south of Carentan, toward Periers. After that costly

assault, von der Heydte had reportedly returned captured American first

aid men with a note to Maj. Gen. Robert C. Macon, the division

commander, saying that he thought Macon probably needed them. The German

commander had also requested that, if the situation were ever reversed, he

hoped General Macon would "return the favor." The result on July 4 had

been a three-hour armistice in which 16 seriously wounded Americans were

evacuated to the aid post in addition to those recovered from the German

aid station. At the same time, wounded Fallschirmjager troops that had

been taken to the American aid stations were turned over to German medics.

As the search continued for wounded troops on the

23rd, both sides lent their energy to the

recovery effort. An American newsman reported that at one point Chaplain

Hamilton was hailed by a German paratrooper who was manning a machine-gun

post. The gunner pointed out to Hamilton that he had overlooked a wounded

soldier. As he moved toward the overlooked man, Hamilton came upon yet

another man, whose left leg had been shot off. It seems likely that one or

both men may have been wounded by that same gunner. After the war, former

paratroopers Karl Bader and Othmar Karrad told stories of how German aid

men and paratroopers had supported the chaplains' and litter-bearers'

efforts near the Seves.

After a three-hour truce, the fighting resumed.

Never again did the 90th Infantry

Division suffer the indignity of surrendering so many men

and officers--a total of 265--to the Germans. In fact, the

division gave much better than it received, ending the war

with many battle honors and a reputation as being among the best American

divisions.

The story of the truce

was published in the United States, providing a glimmer of hope during the

difficult summer of 1944 to Americans who had feared that civility and

chivalry on the battlefield were a thing of the past. Outside of the 6th

Fallschirmjager Regiment, however, few Germans heard anything about von

der Heydte's agreement to a compassionate trace.

The 90th Division's

failure to take Seves Island on July 23 was, after all, a minor setback.

At the end of July 27, the Americans had occupied St.

Germain-sur-Seves--by then abandoned by the German paratroopers--and moved

on to liberate Periers. Major General Eugene Landrum was relieved of

command shortly after the Seves debacle and replaced by Brig. Gen. Raymond

S. McLain. At that point the 90th's fortunes began to change. McLain,

described as an "exceptionally able officer" by Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley,

commander of the U.S. First Army, led the 90th as it participated in

Operation Cobra. In the end, according to General Bradley, the 90th

Infantry Division

"became one of the most outstanding in the European Theater."

Sergeant Alexander

Uhlig's counterattack was one of the last successful actions fought by the

Germans in Normandy. On October 24, 1944, Uhlig was awarded the Knight's

Cross for his daring mission at St. Germain-sur-Seves. He was later

captured by members of the 90th Infantry's 357th

Regiment and spent the rest of the war in a prison camp.

One artillery battalion providing reinforcing

fire for the 90th Infantry Division

at tack on Seves Island was the 333rd Field

Artillery Battalion. The battalion was one of the many 155mm howitzer

battalions made up of black enlisted men and white officers that fought in

Europe in World War II. From the time it fired its first rounds on July 1,

1944, until it was reattached to its parent artillery group on July 27,

the 333rd saw duty with the 90th.

The accuracy of the battalion's fire was such

that it soon earned the sobriquet of "Rommel, Count Your Men." Every round

was reputed to take its toll in enemy casualties. As a result, after every

fire mission, the famous German commander in Normandy, Field Marshal Erwin

Rommel, was advised to count the number of men lost to the 333rd's

fire.

During its attack on Seves Island, the battalion

provided reinforcing fire to the 344th Field Artillery, an organic 90th

Infantry Division

artillery battalion, which fired in direct support of the 358th

Infantry Regiment. However, along with the other

artillery fire, the 333rd's efforts were of no

avail in assisting the infantry to fight off

Sergeant Alexander Uhlig's paratroopers.

A Lieutenant Gibson from the 333rd

was sent into battle on the 22nd with the 358th's B Company as a forward

observer. The artillery battalion's unit report stated he "suffered from

contusions of the eye from blast." His radio was also destroyed in the

attack. Of B Company's five officers, four became casualties that day. To

replace Gibson, a Lieutenant Osburn, who had been attached to another

organic 90th artillery battalion, went forward to join what remained of

the 358th's battalion. He was captured the next day, on the 23rd,

along with the rest of the 358th's officers and men.

In the Battle of the Bulge, the 333rd

was virtually destroyed. It was firing in support of the 106th

Infantry Division when the

106th was overrun in mid-December 1944. Although the battalion managed to

get three of its 155mm howitzers to Bastogne, where its men continued to

gallantly fire their pieces, the 333rd Field

Artillery Battalion never fired a round in anger again after the first day

of 1945. Without enough qualified gunners to make the battalion combat

effective, its remaining personnel performed guard and other duties until

the end of the war in Europe.

On a more tragic note, 11 black soldiers of the

Service Battery of the 333rd were massacred near

Wereth, Belgium, on December 17, 1944. Separated from their unit when it

displaced to the rear in the face of the massive German attack, the

American troops were overtaken and murdered by mechanized infantrymen as

they fled over frozen roads. The perpetrators of the slaughter were never

identified. It was not until 1998 that the victims were recognized and

their relatives were given the awards earned by the deceased soldiers.

R.E.B.

Below left: The 6th Fallschirmjager's Company 16, led by Sergeant

Alexander Uhlig, mounted counterattacks against the 1st and 2nd battalions

of the 358th Regiment, 90th Division, after the Americans

pushed across the Seves River on July 22.

PHOTOS (COLOR): Left: In a painting by Max Crace,

a German paratrooper armed with a Fallschirmgewehr 42 assault rifle draws

a bead on American troops in Normandy. During the seesaw battle for St.

Germain-sur-Seves in July 1944, inexperienced men of the U.S. Army's 90th

Infantry Division were

trapped by counterattacking Germans of the 6th Fallschirmjager (Paratroop)

Regiment (Hammer). Above: The 90th Infantry

Division emblem (Rick Brownlee, R&B Graphic

Design).

Left: This memorial commemorates the 90th Division's

sacrifice at St. Germain-sur-Seves.

PHOTOS (BLACK & WHITE): Top: 90th

Division troops march forward in the Cotentin Peninsula in

July 1944. Many of the GIs who faced Fallschirmjager forces in the

struggle for what became known as Seves Island were green replacements.

Above: An aerial view shows some of Normandy's hedgerows, which proved to

be formidable obstacles for American ground forces and armor.

PHOTO (BLACK & WHITE): American artillerymen fire

a howitzer in Normandy. The 333rd Field

Artillery Battalion, one of the units that provided supporting fire at

Seves Island, went on to earn an impressive nickname thanks to its

accuracy.

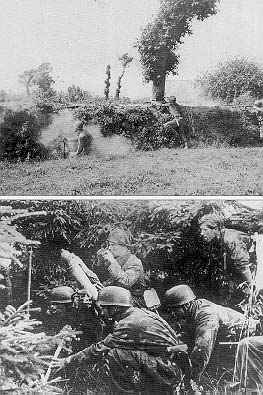

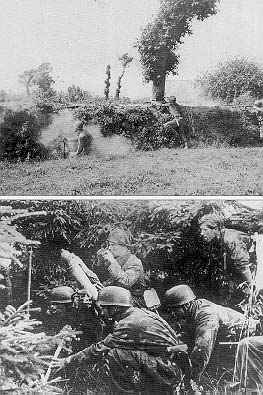

S (BLACK & WHITE): Top: Using a hedgerow as cover, one GI fires a

rifle grenade from his M-1 while two others provide supporting fire.

Above: A Fallschirmjager mortar team, advised by a spotter, prepares to

fire an 81 mm mortar into the American defenses from a well-concealed

position.

Left: German paratroopers wore special uniforms--including camouflage

jump smocks and Luftwaffe eagle insignias--that distinguished them from

regular Wehrmacht troops.

PHOTO (BLACK & WHITE): Below left: German Major

Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte (at left), who commanded the 6th

Fallschirmjager Regiment in Normandy, agreed to an informal truce on July

23.

~~~~~~~~

By Raymond E. Bell Jr., Brig. Gen., U.S. Army

(ret.)

Adapted by Brig. Gen.

Retired Brig. Gen. Raymond E. Bell, Jr., writes

from Cornwall-on-Hudson, N.Y. Suggested for further reading: Normandy

Breakout, by Henry Maule; and Breakout and Pursuit, by Martin Blumenson.

Copyright of

World War II

is the property of Primedia Special Interest Publications and its

content may not be copied or e-mailed to multiple sites or posted to a

listserv without the copyright holder`s express written permission.

However, users may print, download, or e-mail articles for individual

use.

Source:

World War II, Feb2000, Vol. 14 Issue 6, p42, 7p |

|