http://www.naval-history.net/WW2MemoirAndSo08.htm

|

AND SO ...

8. GERMANY

AND STALAG VIIA

..... from

Salonika by train - for the start of "a strange life" |

|

|

|

| Came the next forenoon with the

roll-call of numbers, we were told this was the day we would be on

our way to Germany. The sky was filled with black clouds and we were

not allowed to go into the hut. At noon we were told to line up to

collect our soup; just as my turn came the heavens opened and the

rain bucketed down, such that in no time my ration of soup in my

Army-issue dish was displaced by rainwater. To cap it all, the rain

stopped and as the sun attempted to shine through a break in the

clouds I looked to the sky to see a long silver edge in those clouds

and I can still hear myself saying, as I attempted to gain some

consolation, "Every cloud has a silver lining." One of the old

folks’ expressions that I must have gathered.

The rainwater was running off all of us and we waited

for the sunshine to dry us. Eventually it made an appearance,

together with armed Jerries and their cacophony of "‘Raus, ‘raus,

los, los" and we were on our way. I can’t describe it as marching,

more like trudging, until we came to a railway goods yard, to find a

train of cattle trucks assembled. How did I know that they were

cattle trucks? Because they were French wagons and on the side of

each of them was stencilled "10 CHEVAUX - 40 HOMMES". When loading

the wagon in which I was, Jerry didn’t stop at ‘40 hommes’ - must

have been nearer fifty, but as each of us climbed into the wagon we

were issued with a whole loaf and a tin of German meat, apparently

similar to the front line German soldier’s ration. They must have

run out of bully beef from the York’s Stores. |

|

The Prisoner of

War tags issued to Harold Siddall in 1941, bearing the camp name

Stalag VII/A and number 5850 |

| |

|

|

| The German Army seemed in a great

hurry to win their war, but when it came to moving us P.O.W.’s, or

‘Kriegies’ as we began to call ourselves, they seemed to lose

interest. Once the requisite number was pushed and prodded into our

wagon the sliding door was shut and latched, and that was that. At

the top corner of each side of the wagon was a tiny barred opening

and there was a minimum of straw on the floor. All we could do was

organise ourselves into a fair distribution of bodies on the floor

and it was agreed that as soon as we could discover the direction of

the wagon, we would attack a rear corner of the floor to make a hole

for toilet purposes. It was going to be a long job because amongst

us there was only a collection of knives with shortened blades. The

words for the two types of conveniences in the German language are

‘Abort’ and ‘Pissort’ and soon these words could be heard being

shouted from the nearby trucks, but Jerry didn’t seem to be

listening.

Eventually the shunting began; forward, backward,

stop; this exercise continued for some time until at last we were

off. Having established a direction, we took turns in attacking a

square section in the rear corner of the floor until darkness

stopped work. Next morning the train stopped and we were let out for

toilet purposes. By now we had collected a German Jew who had become

a member of the British Army Pioneer Corps. Known as Harry, he

became our interpreter. Together with the German officer in charge,

he let us know that, when possible, we would be let out each morning

somewhere along the line and given a hot meal. Any damage caused to

German equipment would be sabotage, and that meant shooting. Needs

must, so once back in the wagon we again took turns to make the hole

in the floor. From conversations with other wagons’ occupants when

in a crouched position with trousers or shorts down, we learned that

a number of holes of convenience were being made! When out of the

wagons we were guarded by lines of troops each side of the train,

together with machine-gunners on the roof. These were long days,

spent delousing; those little creatures were still with me and of

course there was not the luxury of a strip-off wash in a horse

trough.

After some days the food supply had been used up;

with the heat in the wagon the meat in the tins, once opened, could

be literally poured out and the bread became rock-hard and sour.

Hunger set in and the promised stops became few and far between. The

train often stopped, but not for our convenience. Late one night,

somewhere in Yugoslavia, the train stopped at a station; we were

"‘raused" out and found ourselves packed together on a platform,

well guarded. We almost had bayonets up our bums, so packed and

guarded were we. Jerry must have realised the mistake, because we

were once more herded back into the wagons and the doors slid shut.

After forever the door was opened; out we came to form a line and

slowly inch forward to people ladling goulash into our containers

and handing out blocks of bread. The fellow handing out my ladle of

soup said in English: "It’s only horse meat ", as though

apologising, but I couldn’t have cared if it had been made of the

camel shot weeks ago. It was beautiful, and if real goulash tastes

like that, roll on! That soup was hot and the memory of the taste of

the bread, after being dunked, makes my mouth water even as I am

writing this episode, fifty two years afterwards.

Once again loaded and locked in the wagon, the

train stayed at that station and the guards lined each side. One of

the wags in the wagon, come dawn, called out to the guard: "Please

may I go to the toilet?" All he received was a snarl of: "Ruhe",

which must have meant "Get stuffed".

And so the train proceeded, stopping frequently to

let other traffic pass. One fine morning we actually stopped for a

convenience call which sticks in my memory because a number of

youths appeared carrying packets of apples. They had obviously done

this before and appeared to supply the guards before wandering along

the line, carrying out a barter service. There wasn’t very much with

which to barter, but I remembered my sixpence with a hole in it. I

showed it to one of the youngsters, but he wasn’t very impressed and

wandered on. Perhaps it might have been better if he had not

returned, but he did; pickings must have been poor, because he

offered me four scrawny little apples for my sixpence with a hole in

it. Like a fool I accepted: it was food! And on an empty stomach.

The next morning in that closed wagon I had to make a dash for the

hole in the floor. An apple a day keeps the doctor away! We had only

that one issue of soup over those many days of journeying. Once we

were issued with a small tin of meat and sometimes a handful of

biscuits, as hard as iron. Sometimes the train stopped near a

watering point for engines and from these we collected water, but it

was a precious commodity.

There was not a lot to raise a laugh on that

journey. But one instance comes to mind, when we stopped near an

engine watering point. By this time we were all looking scruffy and

one squaddie decided he would have a shave, using his Rolls Razor.

Not in plentiful supply nowadays, that razor was a compact unit. I

used one myself until the beard-growing days. It went to the bottom

of the Mediterranean when the bows of 1030 were blown off. The blade

could be sharpened by stropping and honing in its case, but the

operation caused a loud clicking noise. Quite unconcerned, the

soldier carried on clicking until the noise caused concern among the

guards, who began to react as though they meant business. The fact

that they were ganging up on the noise made by a Rolls Razor made us

see the funny side. But Jerry, with his poor sense of humour,

decided that enough was enough, and back in the wagons we went. The

guards travelled in passenger coaches and when we finally arrived in

Bavaria, at Stalag VIIA, a Prisoner of War camp near Munich, they

were relatively fresh, whereas we were smelling a bit high, to say

the least.

Unloaded from the wagons, formed up and counted

and counted, we were herded along until we came to the entrance to

Stalag VIIA, where there was a large metal arch, on which were the

words: "ARBEIT MACHT FREI". This was translated by our Harry thus:

"Work makes Freedom."

We were taken into what could only be described as

a sheep-shearing shed, where French P.O.W.s were wielding

hand-operated clippers for the purpose of shearing our heads of

hair. When my turn came, my tonsorialist was as good as the next,

because I was completely shorn. When I pointed to my beard he shook

his head negatively; there was nothing on the daily orders about

shearing beards! Now our predicament caused a lightening of spirits

and hilarity; we just laughed at one another’s appearance. Where

before there had been burnt brown faces, now there were burnt brown

faces and snow-white heads of many different shapes and sizes. I was

the only one recognisable because I still had my beard and we just

laughed at one another because of that sudden contrast. We were

going to one another asking: "Who are you?" When the hairdressing

session was completed, walking in a carpet of different-coloured

hair, we were ushered into the next part of the building to find

several deep circular containers of a thick, yellow, sulphurous

liquid. We were made to strip off and bathe in these containers and

scrub one another’s back. There was another laugh when my

compatriots yelled: "Not you, sailor; we know what sailors are!" We

were told to leave all of our uniforms on the floor, but in the

assembled crowd I picked up my khaki shorts, Naval belt, socks and

boots. Liquid running from me, I went with the others into the

building to be clothed. We had evidently been de-loused, thank

goodness! On the floor were heaps of various uniforms; I was issued

with something like cotton underpants which were secured with a

drawstring, and a shirt of rather coarse material. Then I had to

find something out of the uniforms that would fit me. There seemed

to be very little in the way of anything British, but I did finish

up with a Highland regiment jacket, something worn by a Scottish

soldier as a dress jacket, I would imagine, because the arms were

long enough, but the jacket ended on my hips. The only trousers I

could find to fit me were a pair of Yugoslav soldier’s jodphurs,

which ended just below my knees. So picture, if you can, a British

sailor, with a white bald head, a beard which had gone to seed,

outwardly clad in a jacket which nearly fitted, a pair of something

or other acting as trousers, socks and boots. A pity there isn’t a

picture to complement this description!

When considered dressed we went into another shed

where, seated at tables, French P.O.W.s took down our particulars,

and upon mine I placed a thumb-print. I was given an aluminium,

rectangular identity disc, to be worn around the neck, on which was

stamped ‘Stalag VIIA:5850’. Stamped in two places so that, should I

die whilst in captivity, one half of the aluminium disc would be

sent to the International Red Cross in Geneva. Presumably the other

half would be buried with me.

Then came the inoculation; seemingly the same

syringe was used on the whole batch of us; the inoculation was in my

left breast and it went in like a thump from a heavyweight boxer.

When all had been dealt with we formed up to proceed down the long

road; it was then I realised what a Prisoner of War camp was. On

each side of that road were walls of barbed wire as high as perhaps

fifteen feet, and although at first I didn’t realise it, similar

walls branched off at right angles making compounds. Initially

Stalag VIIA had been a camp for French P.O.W.s and we were the first

British contingent to enter. Confined to their compounds, the French

threw cigarettes to us, together with matches. Those cigarettes were

Gauloises, made from a strong black tobacco and I actually saw some

of our fellows fall to their knees when they inhaled the smoke. At

the bottom of that long wired road was the compound into which we

went.

I chose the middle bunk of a three-tiered set, on

which was a palliasse containing a minimum amount of straw, resting

on seven strips of wood. On the palliasse was a thin, dark grey

blanket and a piece of cloth to serve as a towel. Our evening meal

was ready for us; apparently we had been expected the day before and

the French cooks had been able to save the rations. The meal

consisted of fish soup, and I actually had two helpings because my

aluminium dish was small.

Beside the huts, which formed a square, there was

a lavatory without running water, serving for dual needs -

everything expended into a huge crater. Don’t bother to ask what we

used for toilet paper: there wasn’t any. We took our dish of cold

water and cleansed ourselves. Each hut was in the form of

semi-detached accomodation, divided by a wash-place consisting of

cement troughs into which cold water could run. The windows had

wooden shutters, hinged on the outside; come lock-up time these were

shut and barred by the guards, who also locked the door, effectively

sealing us in. A couple of Alsatian dogs were let loose in the

compound, searchlights from the watchtowers swept the area

frequently: all this to ensure that nobody could do us harm during

the night, I presume!

The first morning saw me wake with an itch - this

time caused by fleas; everybody was the same; the things lived in

the straw and on us. But the first night’s sleep was absolute, due

to the respite from travelling in the wagon, I suppose. But for the

remainder of the time in Stalag VIIA I never had a good night’s

sleep. Fleas and hunger saw to that, and we were all in the same

boat. It was here that I met and formed a strong friendship with Bob

Andrews, known as Andy. We were the only Westcountry people in that

hut: he came from Newton Ferrers; so it was natural that we should

pair off. A bricklayer by profession, when called up it was as a

gunner in the Royal Artillery.

For a few days we were isolated in our compound,

then after roll-call one morning the gates were opened and we were

free to wander into the other compounds, all occupied by French

P.O.W.s who had been there since the French capitulation, about a

year before. When Andy and I wandered into a French hut we were made

welcome and those who could speak English wanted the latest

information we could give. In one hut were P.O.W.s from the Maginot

Line who, when captured, had walked out with all their kit, so their

hut was like home from home. I can’t recall whether they received

any Red Cross Parcels of food, but each month they received thick,

hard, unsweetened biscuits from the French Government which went a

long way towards supplementing the daily ration of food. P.O.W.s

were supposed, by the Geneva Convention, to receive the same

victuals as base-line troops of the detaining power. Each morning we

received a ladle of mint tea and a seventh of a loaf of bread - dark

brown stuff, said to contain sawdust for bulk. In the late afternoon

the food consisted of a ladle of soup: sometimes cabbage soup,

sometimes turnip soup and, very occasionally, fish soup. Fleas and

hunger were the constant tormentors; hunger was there all the time

and all we could talk about was Red Cross parcels.

Then one day we were each given a pre-printed

postcard, on which were the following four sentences: I am well. I

am not well. I am wounded. I am not wounded. We borrowed a pencil

from a French P.O.W. and deleted the lines which did not apply. So

when mine arrived home months later, care of the International Red

Cross in Geneva, it read so: "I am a Prisoner of War. I am well. I

am not wounded." Any additions would cancel the card. When the card

arrived, my Dad and Mabel took it to the Naval Barracks, where I had

been posted ‘Missing in Action’. So at least the Powers That Be

could put me back on the pay register!

One day Andy and I were in the wash-place of our

hut and in our conversation one of us said "Ta", our Westcountry

version of "Thanks". I don’t know what we were thanking one another

for, but just at that moment a P.O.W. was passing by. When he heard

that abbreviation he stopped and said: "Are you from Plymouth?" When

we acknowledged this he said that his home was in Plymstock. It

turned out that he was on his own so we invited him to join us,

which he readily did. He was Jack Adams, a corporal in the Royal

Engineers. And so originated the Three Musketeers from Kriegieland.

Strangely enough his two sisters worked in the same tailoring

factory where Mabel had served her apprenticeship. Small world!

One day I was taken to an office in the German

compound near the camp entrance where my P.O.W. disc and number were

checked against the form the French P.O.W. had completed. When it

was established that I was indeed a member of the Royal Navy, I was

told that I had to make myself ready to be transferred to a Marlag

in Northern Germany, which was a Prisoner of War camp for Royal Navy

P.O.W.s. When? Nobody knew. I just had to hold myself ready to be

transferred.

Assuaging hunger became the main need in those

days; the bill of fare remained fairly constant, except that on an

occasional day there would also be an issue of boiled potatoes,

which worked out at about three each. What a pantomime each issue

turned out to be! In order that each man should have as fair an

issue as possible, the potatoes were put on a clear space on the

stone floor, then shared by size into the number of rows, according

to the number of men in the hut. Talk about microscopic eyesight!

The senior member of the hut had the unenviable job of sorting the

potatoes as fairly as possible, according to size. Once issued, the

spuds were devoured instantly, skins and all. Hard cheese on anyone

who had a bad spud; it was part of his ration.

One day came the buzz that working parties were

being assembled to work for private employers. According to the

Geneva Convention, prisoners of war who were non-commissioned

officers could be made to work for the detaining power as long as

they were not employed in war work. N.C.O.s could volunteer if they

so wished. The bait was food. We were assured we would receive the

same rations as civilian workers in the firm in which we were

employed. Bob, Jack and I stuck together and were rounded up to go

on the same working party. The fact that I was a sailor seemed to be

forgotten and thirty six of us were gathered together to go to a

work camp, known as an ‘Arbeit Lager’, in Munich. Just like the

other members, I was issued with an overcoat of doubtful origin and

quality, together with a pair of cloth gaiters and two square pieces

of flannel called Fusslappe, which would line the inside of the

boots. During my scrounging sessions around the compounds I had

acquired a French Army water bottle, shaped something like a spade;

so I had a small dish, a combination spoon and fork and a water

bottle. I was relatively well-off! We were rounded up, taken to a

hut near the main gate and made to strip off; our clothing was

minutely searched, our identity discs checked. When re-clothed and

counted, we were told that we would be known as the Hauptbahnhof

Partei, so we promptly called ourselves the ‘Op and Offs’. At that

time nobody had a clue what the title stood for, but we soon

learned. We collected a couple of armed guards, were counted once

more, discs checked and we set off to the railway depot. Wonder of

wonders, this time we were put into a railway carriage and rode into

Munich station in style. I was back in civilisation and realised

what I was missing. Several people must have asked the guards who we

were, because they frequently replied: "Englaender" and we were

stared at as though we had come from the moon. We were the first

P.O.W.s they had seen, and from the way I was dressed, they could

have thought I came from the moon! By this time our heads were

showing a bit of fuzz and the once white scalps had changed to a

darker hue from the sun.

Harking back to the Stalag, I recall the French

told us that they used dandelion leaves to complement their menu.

That was good enough for us; we went around the edge of the

compound, as near the trip wires as we dared, and cleared the camp

of dandelion leaves. Dust and all, they had a bitter taste, but they

were food. Pass the mayonnaise, please!

Once out of the station we marched to our work

camp. I am not too sure, but I believe it was a part of Munich

called Pasing. What I do remember is that, like all work camps, it

had a number, 2780A. Here I made my first acquaintance with the

continental figure 7 with a line through it; initially we thought

that the camp number was 2F80A. Each hut contained two rooms with

twelve sets of triple bunks, six on each side, and a bare wooden

table in the centre, taking up most of the free space. The room was

illuminated by a very low-wattage bulb, operated naturally from

elsewhere. The hinged window was double-glazed with shutters on the

outside. 2780A was on the corner of the road, well and truly walled

with barbed wire, but open to view from passers-by. The boundary

trip-wire was for us guests a warning of how close a kriegie could

approach. The camp was evidently owned by the Hauptbahnhof, the main

railway station in Munich, by whom Bob, Jack and I would be

employed. Other huts were rented to other firms which employed

P.O.W.s. The members of our hut consisted of a mixed bag. The

outstanding members, other than we three, were three Australians:

Ron Waddell, Bluey Lee, so called because he had red hair, and Harry

Woodward. They became the Aussie Three Musketeers who, like us,

shared everything - which at that time was nothing.

After being allotted our room, the next operation

was to collect a thin grey blanket and a palliasse, which had to be

filled as full as possible with fresh straw. That evening two tall,

narrow cupboards were delivered to each room so we had spaces in

which to keep our meagre belongings. The first meal was issued and -

surprise, surprise - it was cabbage soup! And, because we were

workers, we discovered, every soup ration would be accompanied by an

issue of boiled potatoes. So came the ritual of laying out thirty

six lines of potatoes, each being as near as possible of

similar-sized potatoes. The same night-time rules applied as in the

Stalag; once locked in, that was that. The window was shuttered, the

entrance door locked, after a short while a guard would bang on the

shutters as a warning and soon afterwards lights were extinguished.

Night-night, pleasant dreams; hope you remembered to go to the

toilet!

Early in the morning four men had to go to the

Kueche - the kitchen - to collect the loaves and a churn of mint

tea. When the loaves had been cut into seven parts, the bread and

tea was breakfast. So each morning five loaves and one seventh of a

loaf were collected. Sometimes there would be a large seventh and

sometimes a small seventh, depending on the disposition of the

German soldier; so regardless of its size, each of us had to take a

turn at receiving the odd seventh of a loaf. Repast consumed and

toiletries completed, there came the German soldier who acted as

interpreter. He could speak American English, and what a bar-steward

he was, as further encounters will explain. When we heard him shout

"Oppanoffparty" our shower mustered outside our hut and we marched

to the main entrance of that closely-wired camp. We seemed to be

counted by every guard in the camp, each armed with a clipboard; we

showed our identity discs and the numbers were checked. We were

advised to learn the German for our numbers, because that would mean

less time standing around each morning. But as one wag was heard to

observe, the longer we stayed, the less time we would have for work!

Eventually we collected two armed guards and marched off in columns

of four to the Railway Goods Yard.

There we discovered that we were to be the

Tick-Tocking Party, maintaining railway tracks wherever required.

‘Tick-Tocking?’ you ask. Yes, because that was the noise made by the

metal pick as it struck the stone ballast to force it under the

wooden sleepers. Sounds easy, doesn’t it? Not so, quoth I. The picks

in question differed from the normal type, in that one end of the

metal part was welded into a fairly large steel ball, which was used

to hammer the ballast under the sleepers. To level a length of

railway line meant that some of the fellows had to jack up the

sleepers while others wheelbarrowed the large lumps of stone ballast

as near as possible to the required spaces; then the Tick-Tockers

would set to work, ramming the ballast into place. After repairing a

length of track, a shunting engine and a cattle truck appeared and

the thirty six of us piled into the truck to ride up and down the

track several times - this to convince the overseers that we had not

sabotaged anything, I presume.

Perhaps when reading this you will find it

difficult to realise that this work was really a type of hard labour

and our undernourished bodies weren’t up to it. Thus it paid to

learn quickly some German expressions. So after a Jerry workman had

gabbled and gesticulated for about ten minutes, he would invariably

end his speech with the expression: "Verstehen Sie?" To us this

meant: "Do you understand?" Whereupon we rapidly learned to say:

"Nicht verstehen." As our pronunciation wasn’t pure Deutsch, it

became standard to say: "Fushstain Nicht" and the standard retort

from the overseers would be: "Nicht verstehen! Nicht verstehen! Die

Englaender verstehen immer nicht. Dummkoepfe!" And that was another

word learned to add to the vocabulary.

To Arbeitslager 2780A was assigned a junior German

officer who was our official interpreter, known as the Dolmetscher.

He was a simple sort of lad whose job was to cycle to the various

working parties to iron out language difficulties - and he had a

full-time job! His interpretation of the English language was on the

weak side. He learned more expressions from us than he had ever

learned at school. We had to use any means possible to avoid work,

so as soon as he appeared it was the signal to drop everything and

crowd around to hear a translation of something said by the civvies,

to ask questions to stretch out the time. The answers were quickly

forgotten when we were questioned by the boss after the Dolmy had

cycled off to the next working party. It sounds hilarious, but that

work was hard labour.

We marched four or five miles to work each

morning, after a breakfast of a thin slice of so-called bread and a

cup of mint tea. All that did was clear the tubes. The dinner-time

break was a half-hour, when we would each be given a small bowl of

cabbage soup. Some of the crowd would bring their bread ration to

eat with the soup, but we preferred to stick it out and have ours

with the evening repast. A favourite meal of the civilian workers

was a piece of fat bacon toasted in front of the brazier; as the fat

melted it would be rubbed onto a piece of bread and eaten. That

smell used to drive us crazy - talk about mouth-watering! I am

certain they did this deliberately to get their revenge for us being

so deliberately thick.

One of the worst jobs on this Tick-Tocking skylark

was when lengths of line had to be replaced. We knew this when the

‘tulip’ spanners were issued and a groan always ascended to the

skies. Using the long spanners, we had to disconnect the fishplates

from the lengths of rail and lift the rail from the sleepers. Jerry

always got his revenge on us on these occasions. There were never

enough of us to lift a length of rail, and they were so heavy. The

ganger would shout: "Eins, zwei, drei, los!", whereupon we would

shout "One, two, six" and endeavour to lift. Under normal

conditions, with normal food, we could have accomplished the job. At

first when lifting, we were placed any old where and there was

nothing concentrated, so we sorted ourselves into similarly-sized

partners each side of the rail, but lifting was still damned hard

labour. Then the replacement rails would be brought and levered off

the long wagon, to be manhandled into place and connected. Upon

completion, along came the shunting engine and the wagon. All

aboard, and the engine would be traversed up and down the section

until the ganger was satisfied.

We had the same two guards each day and one of

them remembered a bit of his English lessons, because at the end of

each long day, when we mustered to march off, he would invariably

say: "Hurry, hurry, it’s high time." So of course he was named

"Hurry Hurry." I remember one evening in September 1942, when

marching back to camp, we were made to wait while a long convoy of

Army vehicles passed us. A crowd of Jewish workers stopped alongside

us and one of them, dressed in what appeared to be a striped pyjama

suit, asked me if I was English. I affirmed and he said: "Can you

give me a cigarette?" When I explained that none of us had any

cigarettes, he asked for half a cigarette, or even a dog-end. I had

a job to convince him that we had none at all. While talking I

noticed that several of the Jews were carrying a brick in each hand.

When I asked the reason for this, I was told that in the opinion of

their guards they had not done a good enough day’s work, so their

punishment was to carry the bricks and return them next morning. I

could not help but think that, had those rules applied to us, we

would be carrying concrete blocks for our delaying moves!

And so those long days passed. Just like the

others, I lived for that return to the camp for the share-out of

potatoes and so-called soup to be eaten with the remainder of the

bread. It was no use trying to save any bread; by the next day it

would begin to smell like fish-glue - besides I for one didn’t have

the will-power.

Then one evening upon return from Arbeit we were

each given a P.O.W. postcard to write our first few words home. We

were told by Dolmy that we could ask for parcels to be sent, but

that the weight limit was ten kilogrammes. Like the others, all I

could think about was food and it was farcical as we prompted one

another with suggestions, expecting that the parcels would be

delivered in a week or two. They never came.

On Sundays there was an issue of jam and

margarine. This worked out to be an Oxo-sized cube of

Tafel-Margarine and a tablespoon of red jam, said to be made from

turnips and coloured with cochineal. As for the margarine, we

arranged to forego the weekly ration and took it in turns to wait,

in order to have a larger portion from the cube. We were paid

seventy pfennigs a day in Prison Camp money; this was printed

especially for us ‘kriegies’ and could only be spent in the camp

canteen which, if I remember correctly, only sold ‘Klingen’, razor

blades, ‘Rasierseifen’, a sort of shaving soap (and ‘sort of’ was an

excellent description for that stuff), and ‘Zahnpulver’, again a

‘sort of’ toothpaste. Each received four marks twenty pfennigs in a

proper workman’s envelope, which was for six days work of nine or

ten hours a day. At that time the exchange rate was fifteen marks to

the pound, so we were never going to be millionaires! Later, a

weekly ration of rather coarse, sandy soap was on sale and we were

allowed a hot shower once every ten days. Other than that, all water

was cold. |

The Prisoner of

War camp currency first used by Harold Siddall in 1941

| In early October the weather began to turn cold

and on those long stretches of open railway track the winds showed

us how inadequate our clothing was. This was a dead loss, because

we had to put a bit of effort into our work in order to keep warm.

There was an agreement between us that when Dolmy next made a

visit we would concentrate on moaning to him about the poor

clothing. After several of these sessions, blow me if one Sunday

large bundles of British Army uniforms didn’t arrive in the

canteen and, hut by hut, we were able to choose clothing of a

suitable fit. These were all parts of captured uniforms which had

been de-loused. Having discarded my comical outfit, I finished up

with a forage cap, brown pullover, an early-issue Army overcoat, a

somewhat-modern issue pair of trousers with leg pouch pockets and

a British Army greatcoat, which was a real treasure-find,

considering there were not many of those coats to fit six-footers.

At the same time, each of us was issued with a pair of mittens,

called ‘Handschuhe’, made from old army materials. And so our

moans and badgering of Dolmy paid off. More about my pair of

Handschuhe later in the tale.

We also collected an Australian Sergeant Major

to be our camp leader; a doctor in the form of a Major in the

Medical Corps and British Army bandsmen who became our medical

orderlies. A German Naval doctor was attached to the camp, mainly

to decide how ill a kriegie was, in order to be granted the almost

unobtainable "Bett Ruhe", which meant "bed rest". Everything was

going to be all right when the Red Cross parcels came, or, better

still, those parcels for which we had written home. |

| By now Jerry was heavily committed

in the war against Russia and each day a civilian would be missing

from the track workers. Enquiries about what had happened to the

missing civvy were always met rather quietly with: "Fuer ein Soldat,

gegen Russland." And to rub it in, the worker would be asked when it

was his turn to go, which would be followed by the answer: "Ich

weiss nicht." When marching to work we saw posters appealing for

gifts of warm clothing for the soldiers on the Eastern Front; this

was their "Winter-Hilfe" - winter help - appeal. Because of working

on the tracks in the cold winds many of us suffered from badly

cracked lips, and the more you licked them, the more painful they

became. |

|

Harold Siddall

and "Andy Andrews" in December 1941 - the first winter as POW's |

| |

|

|

| One morning, dark and

cold, we had Harry ask the German Sergeant Major, who always

conducted the rapid countings, whether we could have some sort of

cream as a protection for our lips. We were told to be like the

gallant German soldiers on the Eastern Front, who used the wax in

their ears to rub on their lips. Just try it. This Jerry was built

like an oak tree and one of the few who did not sport the toothbrush

moustache which most men had, to copy their beloved Fuehrer.

Instead, he sported a large Hindenburg-type decoration. When he

spoke, those guards jumped.

Whilst at work we were frequently photographed, to

be used as material for propaganda. Each month there was an edition

of a newspaper for P.O.W.s, called "The Camp"; the issue didn’t

quite work out to one each so a rota was arranged for turns to keep

a copy, worth its weight in gold as toilet paper - after reading all

the lies, of course. One Sunday, which in the early days was a day

off work, Dolmy came round to tell us to save five camp marks, so

that we could purchase a copy of Adolph Hitler’s "Mein Kampf",

printed in English. He showed us a specimen book and of course the

initial concensus was "Not bloody likely". Then, with afterthought,

the penny dropped. The book was very like an older type Holy Bible -

masses of pages made of good quality thin paper. Were we going to

buy those copies and read about Hitler’s struggles? Yes, three pages

at a time in the toilet! Could we buy more than one copy? No, owing

to popular demand by kriegies to read the valuable work,

restrictions to one copy per person had to be enforced. Poor Dolmy

was delighted with the reception, not knowing to what use the end

product would be put! Over a week’s wages to buy bog paper, but it

was good economics - and good reading, because there was nowt else.

Once again strong buzzes permeated about the

elusive Red Cross parcels; Jerry promised an issue at Christmas, but

then put a damper on it by kindly telling us that the R.A.F. had

bombed Lubeck, a port in the Baltic where the neutral Swedish ships,

chartered by the Red Cross, unloaded those necessary supplies. How

we hated the R.A.F.! They were nowhere to be seen when we needed

them on Crete and now, of all places to drop their loads, they had

to bomb Lubeck. Jerry certainly knew how to twist the knife! The

next excuse was that the railway tracks from Lubeck were being

continually bombed by those "Terror-Fliegers". I don’t suppose any

of our compatriots had ever seen the contents of a Red Cross parcel,

but each evening we slavered over the possible contents of those

beautiful boxes. On one occasion when hunger racked us and the

subject just had to be food, somebody organised a verbal competition

about the best sort of meal. Of course the descriptions varied and

the quantities would have made it impossible for a dinner plate to

be large enough. But one bloke took the biscuit. He described how

his Mum scooped out the inside of brown, roasted potatoes and filled

them with some of the creamed interiors. Then, when the menu was

completely described, somebody asked him what his Mum did with the

rest of the scooped out potato and he calmly replied: "She throws it

away." A howl of anguish arose at this and she was hated for

throwing away succulent food. Such was the power of hunger in those

days, again not helped by the biting wind and the snow. |

| |

|

|

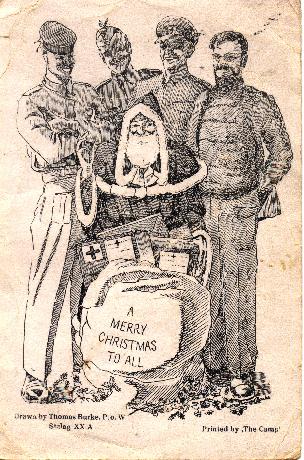

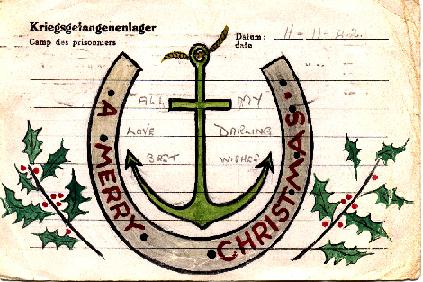

"Regulation issue" Christmas card sent

by POWs at the end of 1941 |

|

Snowballing had long since ceased - how we hated

the stuff! We had to make an effort at work, just to keep warm. The

most affected parts were the feet: boots leaked in the snow, socks

and Fusslappen became wet and the chances of drying them were nil;

we just put them between blanket and mattress and let body heat

work. Many developed chillblains on their toes and fingers and it

was murder for them once we returned to our rooms and body heat

raised the temperature. I count myself fortunate that I was not

afflicted by this. The Aussie, Harry Woodward, developed an ulcer on

his shin, but there was no treatment for it. There was always a

queue hoping to report sick, but the German doctor didn’t seem to

know the meaning of the word. Anybody who collected "zwei Tage

Bett-ruhe" - two days off work - was very lucky. It was a case of no

work, no pay and, what is more, no midday ladle of cabbage water.

On one of those nights tramping back to the

barracks, the wind was bitterly cold and the snow was blowing in

every direction; we entered the camp and after the usual endless

standing whilst being counted and signed for, the Feldwebel told us

that there was mail in the huts. With a whoop and a holler we dashed

indoors to find that some lucky sods had letters; whilst there were

not many, Bob Andrews had received one from his Mum. Jack and I were

not so fortunate, so Andy read his to us. There was no mention of

the parcels for which we had written. Several lines about what the

Red Cross was doing; apparently parents and wives of prisoners were

being put in touch with one another, but nothing about food. Here

and there lines were blacked out by the censors. |

| |

|

|

| One of the guards was a

photographer by profession. When war was declared he was on the

dockside, waiting to board a liner and emigrate to America. Instead

of boarding, he and all the male would-be emigrants were rounded up

and before they knew it they were in the German Army! Being a

professional photographer, he was able to wangle a job in the

propaganda department of the Army. In anticipation of emigrating he

had learned a little English and from his conversations during some

of the propaganda sessions he let loose that he hated the Army,

Hitler and anything they stood for; but this was always expressed in

a very low voice. He was forever wanting to learn new terms and

English phrases, so of course he was taught some choice expressions

by us!

Then, Hallelujah! At our first Christmas there was

an issue of Red Cross parcels. We arrived back at the lager to see a

huge van leaving and all we could hear from the camp guards was:

"Rote Paeckchen!" And we just couldn’t believe it. Once counted,

there was a dash back to the barracks room, consume the soup, bread

and spuds and bubble with anticipation. Then came the news that the

issue would consist of a parcel between two men. Those wonderful

boxes were bound by strong white cord, so here was our first clothes

line to rig up in the room to dry our washing and the boxes could be

used to give each one a sense of privacy. A few years ago, Mabel and

I had a holiday on the island of Jersey and one of the places of

interest we visited was the German underground hospital, carved out

of the ground by Russian P.O.W.s. At the entrance was a Red Cross

parcel box and the sight of it momentarily dimmed my eyes, as they

watered from the memories. Pardon me for digressing; let’s get on

with the story.

What was in that wonderful Red Cross parcel?

Writing this part of the yarn on the afternoon of Christmas Eve

1993, a cold, dry, sunny day, looking at the blue sky from my

breakfast room window, I find myself racking my memory to recall

what was in that box. Here goes. A two ounce packet of tea, a tin of

rice pudding, a tin of condensed milk, a tin of meat and veg., a

packet of Yorkshire pudding mixture, a tin of margarine, a tin of

meat-loaf, a packet of hard biscuits, a tin of jam and a tin

containing fifty Gold Flake cigarettes. There were other items as

well, but my memory fails me.

The boxes were kept in a store controlled by the

Germans and the bloke in charge was the American German, our enemy,

the "bar-steward". We were told all tins had to be opened and

emptied in his presence, in accordance with the Geneva Convention.

He obeyed these orders to the letter initially and, since we had

only one dish each, he was not averse to putting several selections

in one dish. Thus one could leave the store with portions of jam,

rice and meat-loaf all in the same dish. We were allowed to take the

cigarettes separately. Of course this could not be allowed to

continue and we lost no time in hunting out Dolmy to ask him about

it. Even the British doctor could do nothing and we three musketeers

had to carefully plan what to collect in our three dishes, to put

together a satisfying feed as economically as possible. At least we

were able to make drinking mugs out of the empty tins. Try to

imagine, if you can, piping hot tea flavoured with condensed milk!

Paradise! Definitely a better start to the day than Jerry’s mint

tea.

But a drink of tea requires boiling water. In the

hut there was no provision for this and Jerry in the cookhouse

wasn’t interested. So how was this problem overcome? It was here

that cigarettes became the currency. There was a German civilian

general handyman in the camp; he called himself a carpenter, which

in German is "Tischler", so he was called Herr Tisch in deference.

He was bribed to produce some electric flex and a connection. With

these items an enterprising inmate joined each end of the twin flex

to a razor blade and the other ends to the connection. With the

razor blade immersed in the can of water and the connection plugged

into the light socket, we had a heater which rapidly boiled the

water. We had to immerse the razor blade before plugging in and

disconnect before removing it; in this way we could make a brew in

turns. Of course the fuse for lighting wouldn’t take too much of

this, so when Jerry wasn’t about somebody stuck a nail in the

fusebox. We had no more worries, but it’s a wonder the place never

burned down. Innocents abroad!

I have mentioned the string which secured the

parcels. We were asked to donate any spare string to the Aussie

sergeant major, with no questions asked. The outcome was that two

under-sized lads on our work party, one Aussie, the other Welsh,

wove hammocks from the string. One evening they disappeared from the

Tick-Tocking party and made their way to the railway goods yard.

They had gained the necessary information secretly and in the dark

they slung their hammocks between the axles of a goods truck, which

became part of a train travelling to St. Margarethen in Switzerland

- and thus they had escaped. They were the only two in our camp to

achieve this. We knew they were successful because the sergeant

major received a picture postcard from his "nephews", lording it up

on holiday in Switzerland.

Our room’s services were not measuring up to the

work requirement as Tick-Tockers for the German railway. I wonder

why? Anyhow, we were sacked, and our feelings were not hurt. But

this meant we would not be kept at Arbeitslager 2780A because the

railway was not employing us. So it looked as though we would be

heading back to Stalag VII A, and this was not a bright prospect.

That weekend Dolmy came into our room and asked if amongst us there

were any what sounded like "mourers". We thought about it and

realised he was asking for masons. The Firma Winkler was losing its

two masons, called up in the Army, poor sods, and replacements were

urgently required to work on a drain-laying contract in Munich. Now

that was the way for Andy and me to avoid returning to the Stalag.

So we told Dolmy that we were masons; this part is laughable. When

he enquired as to our "mourer" status we didn’t understand, so he

had to dig out his interpreter’s book to find the necessary words.

Andy, being a bricklayer, was a Steinmaurer and I, being a

plasterer, as I told him, was a Mortelmaurer. And we were

accordingly employed by the Firma Winkler. Dolmy also brought the

news that the whole room was going to be employed because of

anticipated call-ups.

So the next Monday morning we mustered to the call

of Firma Winkler. The next part may be humourous now, but at the

time was not so comical. When mustering inside the barrier gate, the

fussy German corporal, who seemed to be always querying and poking

his nose into whatever was going on, asked me if I was a Maurer and

when I replied in the affirmative he followed up with the question:

"Bist Du Freimaurer?" To me it was all the same, so once again I

answered yes. At this he began to slash me across the face with his

gloves and for a moment I could only stand flabbergasted. Then I let

out a roar and called him a good few Anglo-Saxon lower deck titles.

With this uproar going on we were soon surrounded by armed guards,

who must have thought that I was attacking the silly sod. This was

enough to draw the solid oak Feldwebel to the scene, accompanied by

Dolmy. There followed screaming questions and screaming answers

until Dolmy was able to intervene. It seems that being a mason was

acceptable, but being a Freimaurer meant that I was a Freemason and

an abomination in the sight of Hitler and his cohorts, about on par

with Jews. The only thing I knew about Freemasonry was that Uncle

Stan and Uncle John had been members. And so after explanations the

Feldwebel blasted the corporal for poking his nose into affairs

which did not concern him, so Dolmy told me. He had the corporal

standing to attention, stiff as a ramrod, this being as near to an

apology he could offer to me, an enemy, whilst he dished out the

blast, and when we marched off, old Nosey was still standing there.

Of course on the way to the workplace I had my leg pulled something

rotten by the lads and even Hurry Hurry told me that the corporal

was "schlecht", which means rubbish. Such was life!

We arrived at the place of work to find we would

be digging a very deep trench at the side of a fairly long street,

the objective being to lay large diameter pipe sections in the

bottom of the trench to make a rainwater drain. Each of these

sections was pre-cast in concrete and Andy and I would be the

pipe-layers and would build the interceptor pits along the system.

Initially we were with the diggers; of the two tools I found it

easier to use a pick, the soil and the strata was loose, so a couple

of grunts with a pick ensured a bit of a spell whilst the shovel

brigade took over, and those lads had to throw the diggings fairly

high onto the upper stage of the scaffolding, from where it was

shovelled into heaps at the side of the street. This went on for a

couple of days and then Dolmy cycled onto the scene. We must have

been making some progress because Herr Winkler seemed satisfied

until Dolmy asked where the two mourers were; when he saw Andy in

the bottom of the trench digging, he blew up. The mourers shouldn’t

be digging, they should be mouring, but really at that time there

was no construction work for us to do. The outcome was that we went

to assist the surveyor, handling the T-shaped boning rods, with

which he ensured the slope on the bottom of the trench was correct.

Heavy work that! In my earlier writings I mentioned the Standard

Inn, where I was a member of the darts team; the Manager was called

Percy Hemer. Just keep this in mind.

With a section of the digging in the trench

completed there arrived a lorry-load of pipe sections. There was no

space to store them, so the garden of a hotel opposite was

commandeered. The hotel was called "Ost Wirtschaft" and the owner

was a Michael Hemer! Any relation? I don’t know, but just fancy

having to enter Kriegsgefangenschaft to find another Hemer! Seems as

though I am waffling.

With the pipe sections in the Biergarten, Andy and

I came into our own. Before laying the pipes in the drainage site,

the insides had to be sealed with a cement wash; the pipes being

almost a yard in diameter, we were able to crawl inside to do this.

Adjacent to the beer garden was a house with a metal railing

balcony. Now the Honorable Robert Andrews was gifted with not too

bad a voice and one morning Andy was inside a section of pipe,

slapping cement wash all over and busily singing the "Woodpecker

Song". It didn’t sound too bad and suddenly we heard a call which

sounded like "Harold", so I scrambled out of the section of pipe for

a look-see. Nobody in sight, but again came the call and this time I

realised it was "‘Allo!" I looked up and there, standing on the

balcony, was a vision in the form of a girl with long blonde hair.

Andy was still singing away inside his section of the pipe and I

have to admit the tune was not too bad. The vision asked me if I was

English and after my reply she wanted to know the name of the song

coming out of the pipe. I called Andy and when his eyes had gone

back into their sockets he proceeded to give the girl the full Bob

Andrews treatment. He had a charming smile and a pleasant voice and

was soon able to enlighten her. Her command of the English language

was good and she appeared to have a number of records of the latest

songs, mostly sung by Bing Crosby. But the "Woodpecker Song" was new

to her and would Bob sing it again for her? Like a lark on the wing

he obliged and next she dropped a folded sheet of paper together

with a pencil for him to write out the words. Just like Romeo, had

there been a suitable trellis Bob would have personally delivered

the missive to the balcony, but ‘twas not to be, so the song sheet

was delivered wrapped in a stone.

She was full of thanks and asked what she could

give us in return; the spontaneous answer was: FOOD. She left the

balcony and we waited, but neither she nor food materialised, so it

was back to work, slapping cement inside those cylinders of

concrete. The day passed with no more "‘Allo"s and it ended like any

other day at that time. The next morning came another "‘Allo" and

there was the girl. She motioned for silence with a finger to her

lips, looked around as a cautionary procedure and then dropped a

newspaper package. Immediately opened, it contained the cob end of a

loaf, four small tomatoes, some salt in a spill of paper and a sheet

of paper requesting the words of any of the latest songs we could

think of. Now I am not a lover of tomatoes, but the shared bread and

two tomatoes with salt was as good to me as the Manna was to the

Israelites in the time of Moses. I had forgotten the taste of salt

and its succulence made me realise what I had been missing.

Now we had to play this game carefully, not to

expend the repertoire too quickly, so we began with the words of

"Little Old Lady" - an earlier song by Bing Crosby, threw the

pencilled song sheet to her and Andy, once more inside a pipe

section, sang the song a couple of times. Then once more she left

the balcony. We must have been progressing favourably because after

a couple of inspections Herr Winkler left us alone and Hurry Hurry

locked the garden gate, so as far as he was concerned we were

secure. The "‘Allo"s did not come every day, but when they did there

was always the cob of bread, four tomatoes and salt wrapped in a

sheet of newspaper. The newspaper was invaluable; it helped with the

learning of German words, which at times proved very difficult

because the text was in Gothic print. The parts of the "Volkischer

Beobachter", cut into six inch squares, helped to take the strain

off "Mein Kampf" and we asked the girl for more newspaper - for

learning German, of course - and occasionally we would see a

complete newspaper come sailing over the high railings of the

Biergarten. On one occasion the girl was on the balcony, listening

to Andy rendering the latest in the repertoire, when a newspaper

came over the railings; I climbed to see who the supplier was and

saw a lady pushing a bicycle. She put a finger to her mouth, mounted

the cycle and rode off down the side-street. When asked, the girl

told us the lady was her mother and that her father had been killed

early in the war. We asked how she came to have a collection of

records and she told us her brother was a guard on the railway, who

frequently travelled to Switzerland, where he had bought them.

Eventually enough trenching had been created for

Andy and I to begin the pipe-laying, with each section resting on

two bricks, the joints plugged with oakum and sealed with cement. We

would lay the sections fairly quickly, build inspection pits, with

special sections into which we fitted metal crampons as foot rests;

then we returned to the garden to treat the awaiting sections. One

morning, whilst Andy and I were working in the Biergarten, following

the awaited "Allo", the girl asked us if we were allowed out of camp

on Sundays to walk around Munich and was astounded when we fell

about laughing at the suggestion. I still had my beard and my blonde

hair was a respectable length and she told me that, being tall and

blonde-haired, I would easily pass for an example of a Saxon German.

She had thought that because we were workers in Germany we had a

certain freedom, like many conscripted workers from occupied

countries. When we asked why she had raised this question, after

much careful looking around as, she replied that, firstly, it would

help her to increase her knowledge of English and, secondly, if we

were always so hungry we could buy some bread and tomatoes. This was

the opening which we had been seeking. Wrapping some of our Camp

Marks in a piece of newspaper weighted by a stone, we threw the

parcel up to her and asked if she could buy anything with our kind

of cash - preferably a loaf of bread. Of course she had not seen any

of this rubbish before and said that if we had German money her

mother would buy us a loaf of bread.

It was then a case of "on thinking caps". The camp

guards were rationed to three cigarettes a day, when they could find

them, and the latest supplies were from Russia. Each consisted of a

cardboard tube, at the end of which was a small cylinder of black

tobacco, which meant that after a couple of sucks from the cardboard

tube, cigarette finito! The name of those cigarettes was Mokri

Superb. What a mockery! So our cigarettes became currency, but the

only snag was that a guard was in trouble if he was caught smoking

an English cigarette. Those who could not obtain our cigarettes

would sell a fortunate comrade down the river. The best was to deal

with a guard who was on his way home or on weekend leave, because he

could collect a food ration ticket for three days. We found Hurry

Hurry was due for leave and persuaded him to do a deal for his bread

coupons and German Marks. Both Andy and Jack smoked, but I didn’t,

so there were enough cigarettes in the kitty to do a deal and we

were able to obtain the cash and coupons. The next time the vision

appeared on the balcony we threw up to her our supply of one-Mark

notes with a request for bread to be purchased. The next "Allo" came

from over the garden railings, this time from the girl’s mother. She

was asking for the bread coupons, which we had completely forgotten.

So next day, following the welcome sound of "Allo" from over the

railings, we gave the lady the "Brot-Marken", as they were called,

entitling the purchaser to so many grammes of bread. The girl’s

mother, whom we called "Meine Frau", must have been sympathetic to

Andy and me because she often shopped with her bicycle and stopped

by the railings and rang the bell of her bicycle. As long as we

could supply the bread coupons she would not take the money and

became a good friend. |

| |

|

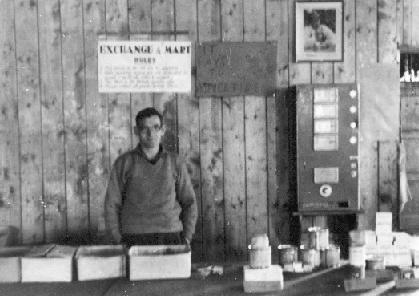

|

Shop where working tokens

could be exchanged for (mostly worthless) articles. Right hand

notice says "IT PAYS TO ADVERTISE!" Photograph taken in 1942

| Our Red Cross parcels issue worked

out roughly at one between two at three-weekly intervals. On one

occasion we were issued with a parcel each and agreed between the

three of us to give Meine Frau one of the two-ounce packets of tea.

When the bicycle bell tinkled, we threw the packet, wrapped in

newspaper, into her shopping basket and motioned her to ride off.

Some time later from the balcony came the "Allo" and there was the

girl with her mother. The girl had tried to teach her mother to say

"Thank you very much." But mother finished up crying and covered her

face with her apron before going back into the room. Meine Frau was

good to us. On another occasion we had received an issue of goodies

from America in the form of toiletries, including toilet paper. We

each received several cakes of soap and agreed to give one to Meine

Frau. I remember it quite well; the soap was a large, bath-size

piece with a swan embossed on it, and it was perfumed! The mother

had difficulty organising her tongue to make the "th" sound, but she

was learning to express her gratitude, and that was all that

mattered. I say again, during those hungry days before the arrival

of those parcels Meine Frau was good to us.

You remember me calling the Yankee German a ‘bar

steward’. (Say it quickly and you will get the message.) He started

a racket when we went to the parcel store to collect an item or two.

He would place the chosen tin on the store counter and go through

the motions of opening it. If you gave him a couple of cigarettes he

would just open the tin; if not, he would empty the contents into

the dish with other choices. No cigarettes and there would be a

mixed dish. He must have been his own downfall, flashing the

cigarettes around, because not long after starting his racket he

disappeared and, according to Hurry Hurry, he had been sent to the

Russian Front. There were great rejoicings when we learned this and

even greater rejoicings when the Camp Commandant allowed us to have

the parcels in our rooms.

The next requirement was a source of heat; such

foodstuffs as meat and vegetables tasted better when heated. The

German photographer became the initial supplier, bringing in boxes

of Meta Tablets, a form of compressed methylated spirit which burned

with a clear blue flame. I cannot remember the precise details:

suffice to say that cigarettes were the main form of payment,

followed by the two-ounce bars of chocolate which came in the Red

Cross parcels. His propaganda visits were usually short-lived, so we

had to cultivate other guards and with them chocolate had priority;

they were fearful of being seen smoking English cigarettes in camp.

You must realise that chocolate was a source of food and we were

reluctant to part with it. Surprisingly enough there were bods in

the camp who were always ready to swop their chocolate for

cigarettes. The Lady Nicotine must have had a stranglehold on them.

Somewhere in the camp an enterprising kriegie had

done a deal with somebody on the outside and come into possession of

a circular electric hob. The news of this achievement spread through

the camp like quicksilver; in no time at all negotiations were under

way to purchase something similar. Those electric hobs were very

expensive and cigarettes were the necessary currency. So the

occupants of each room pooled cigarettes in order to have two rings

per room. Some civilian was onto a good racket, being able to deal

in such a commodity, because by then everything was diverted to the

war effort. Each room had to wait until the shutters over the

windows had been closed externally, then the two-way adaptor was

fitted into the light socket and, according to the roster, meals

were produced by the groups at the top of the list. I had previously

written about having a French Army water bottle, which was shaped

like the Ace of Spades on a playing card. With a tin opener on a

soldier’s knife I cut out one side of the water bottle, hammered a

piece of wood into the neck ring and - hey presto - there was a

frying pan. Each morning the two cookers were placed in an empty Red

Cross box and stowed in one of the two cupboards.

Of course, this luxury couldn’t last. Trouble came

when the consumption of electricity had risen beyond all

expectations and the nail in place of the fuse wire was found. There

was a hell of an uproar and cries of "Sabotage" exploded from every

German mouth, and sabotage was punishable by death! Of course to

Gerry there was no accounting for this extra demand for power; the

lighting was about half a candle-power and the kriegies were using

Meta tablets. Puzzlement all round, but not for long. Next evening

on return from work we found everything from each room outside on

the ground: beds, bedding, cupboards and contents strewn everywhere

and we had our first visit from the Gestapo. They were of all shapes

and sizes, but readily recognisable by their long black leather

coats and their grins, together with the confiscated electric rings

and one idiot holding up the nail which had done such good work in

place of the fuse. We were made to form up outside our blocks, while

a senior Gestapo member worked himself up into a frenzy and,

according to Dolmy, declared that everything except fresh air was

"strengst verboten". The supply of Red Cross parcels was stopped,

the hot shower once every ten days was stopped, mail in and out was

stopped and anything else he could think of was stopped; plus we

would be rigourously searched each time we returned from Arbeit! So

there!

Once released we gathered the contents, made the

room ship-shape and waited for the supply of rations from Gerry;

even our Meta tablets had been trodden on and ground underfoot.

There must have been some chastisement served out on the other side

of the barbed wire. Next morning we were counted and counted, the

Camp Commandant was there and everybody seemed to be trying to

outshine the others, shouting louder than the next counter. On the

march we could usually converse with the guards, to help improve

their English, but not today. Of course we could talk amongst

ourselves and the main topic was how to get around the suspensions.

The only shot in our locker was to copy the French method, which was

passive resistance. In other words, don’t refuse, just work as

slowly as possible without completely stopping. We adopted an

Italian expression: "Dopo domani, Giorgio", and it was a case of

putting off until tomorrow what you can avoid doing today. The word

spread throughout the camp that dead slow was to be the speed.

Amongst our camp members was a working party whose

job was to unload large railway trucks and disperse the goods to

other trucks for onward transport. Of course the goods trucks had to

meet a schedule and this was soon upset. The trench diggers on our

party worked so slowly that the Biergarten was piled high with pipe

sections; very few sections were laid. Herr Winkler wanted to know

why production had become so poor. We told him that in camp there

was "viel Hunger", because Red Cross parcels had been stopped and as

a result we had no strength. Each morning dozens of us took turns to

report sick; it came to nothing, but we had to wait in camp until

the Gerry M.O. appeared to pooh-pooh all hopes of time off, then

guards had to be found to march us to our workplace. Dolmy had to

ride around every work group, explaining to the bosses why the work

rate was falling and to confirm that the delivery of Red Cross

parcels had been stopped. This didn’t go down too well, since the

civilian strength was so sadly depleted through the demands of the

armed forces. All that remained was an elderly force of civilians -

and not too many of them.

It was necessary to keep our room clean and tidy,

but we had to organise our own cleaning gear. So we procured two

pieces of wood from Herr Winkler and had him drill a series of holes

in them; then we knotted two pieces of Red Cross parcel cord to the

flat wood; one piece became a hand scrubber and the larger became a

floor brush. One kriegie from each room was allowed to "go sick"

each day and it was his job to brush out the room, tidy up the place

and scrub the floor with the improvised hand scrubber, using scraps

of soap when available, and sand when there was no soap. Because I

was the only sailor in our room and because of the high regard in

which the Navy was held, I was elected "Zimmer Fuehrer", i.e. Room

Leader, but because I was also a mourer I was not allowed to take a

turn in having a day off work to do the "sauber machen" - cleaning,

that is. We agreed to make a few rules amongst ourselves and one was

a Navy rule. In the Navy, anyone guilty of leaving an item of

clothing outside his locker would find that it had been put into

what was called a "scran bag" and could only be retrieved on payment

of a piece of soap, which was then used to keep the mess deck clean.

No soap, no item returned and, as the owner’s name was stamped upon

each item of clothing, the miscreant was soon recognised and would

face the wrath of the "Chiefie". So, when soap was available, we

agreed in our room to follow this example, and of course scraps of

soap were better than sand.

In the days of writing this story I am plagued by

arthritis in every joint of my body. One morning in 1942 I awoke

with the most excruciating pain in my left shoulder and any movement

was horrible, such that I had to report sick. Being a mourer, at

first any chance of being allowed to report sick was firmly denied.

But I finally convinced the Feldwebel that I was in great pain and

he allowed me to remain with the "dead and dying". The British Army

Medical Officer, who had little power, took me to the medical hut to

be inspected by the German M.O. "Abandon hope, etc." After swinging

my left arm around as though he wanted to unwind it from my body, he

asked me what service I was in and where I was captured. He had me

sit down and tell him about our action off Crete and recount the

events leading up to captivity. He was enthralled and commented that

the long hours in the sea had eventually taken their toll. Wonder of

wonders, he gave me a sick note for the Feldwebel: "Drei Tage

Bettruhe." This meant three days in bed and I collected six of what

I think must have been aspirins. The Feldwebel looked at me in

amazement when he saw the sick note, entered my number, 5850, in his

notebook and told me that I would be my room’s cleaner for the next

three days. So much for Bettruhe!

On the third day I reported to the Feldwebel, only

to discover that I had to carry a thumping great sack of boots to

the railway station, to be returned to Stalag VIIA, where they would

be exchanged for an equal number of repaired boots. Of course I

would be accompanied by an armed guard. By the time we had reached

Munich Station that sack of boots weighed a ton. At least we rode in

a passenger compartment, but no-one else was allowed to join us. We

arrived at Moosburg and trudged to the Stalag, where I took the sack

of boots to the French cobblers’ workplace, after receiving

instructions to be at the main gate by a certain time, early in the

afternoon. Whilst waiting for the repaired boots ther French

cobblers gave me a bowl of thick cabbage soup and a bag of their

hard biscuits, so the journey had become worthwhile. Once at the

main gate, I was collected by my guard and we trudged to Moosburg

Station, to ride back to Munich.

Alighting at Munich Station, the guard took me to

a newspaper stall and told me to wait while he went off somewhere.

With the sack of boots on the ground, I just stood there looking at

civilisation. After a short while a German woman armed with an

umbrella came toward me and began to gabble away to me in an

agitated manner, her voice becoming louder and louder. I couldn’t

understand a word she was saying so I turned away from her and with

that she set about me with her umbrella. By now there was a ring of

civilians around us and all I could do was protect my head; she was

certainly good with her umbrella. It seemed ages before the guard

came onto the scene and at first he thought that I had caused the

ruckus. There was screaming and shouting until he snatched the

umbrella from her and roared at her, whereupon she began crying. It

seems that her husband had been killed fighting the French and,

seeing me by the bookstall in a foreign uniform, she thought I must

be French and decided to extract her revenge. The guard bellowed and

I recognised: "Englander! Kriegsgefangener!" He took me and the

boots to the station exit and back to the camp. By means of

gesticulations and my little understanding of the German language,

the guard conveyed to me his wishes that I should not report the

incident on the station platform. He should not have left me alone

while he sloped off on some nefarious expedition and stood to face

the wrath of the Feldwebel. Of course, the guard was not allowed to

get off scott-free; he had no Brot-Marken, so I settled for a few

German Marks. T’was all grist for the mill, m’dears.

Whilst writing this piece, for what it is worth I

have remembered the name of the Feldwebel - Herr Weiblinger,

although it adds no value to the particular reminiscence.

Of course, by now each party was thoroughly

searched upon return to the camp from work. Several of us had,

through barter, obtained German Meerschaum pipes and on this

occasion I had obtained a supply of German Marks. Knowing that a

search was inevitable, I had to figure where to hide the Marks. Out

came the Meerschaum pipe, the money was stuck in the bowl and pipe

in mouth I marched into camp, was body-searched and, seemingly all

clear, was allowed to enter the compound.

Meta tablets again became the source of heat

supplies, so with the aid of the razor blade immersion heater and

tablets we could have our cuppa and heat the contents of a desired

tin from the parcel. Because the "Lagergeld", camp money, could

purchase very little in the camp canteen, we soon began to

accumulate fairly large sums of useless paper and on Saturdays had a

fair amount in hand. Razor blades, blocks of toothpaste and tins of

dubbin were all that were on offer and even now I still have a

couple of Lagergeld pfennig notes in my kriegie wallet. More about

the wallet later.

Eventually the road works with Firma Winkler ended

and on the last afternoon Herr Winkler gave each one of us six

plums. There were many shouts of "Auf Wiedersehen" and as we paraded

to be counted Andy and I saw Meine Frau standing by the railings.

There was no sign of the vision, no more "Allo’s" from the balcony,

but as we marched away and passed our benefactress we shouted: "Auf

Wiedersehen! Wir Kommen wieder!" But of course we never did,

although I am sure we left pleasant memories with that good lady. I

wonder if the Ostwirtschaft Gasthaus escaped the rigours of the war.

Is the house with the balcony still standing?

Jack, Andy and I were still together, which was

the main thing and, what is more, we shared everything. Personal

parcels from home were starting to dribble in, but those first

requested food parcels never saw daylight. Even money Gerry never

sent them. The personal parcels were mainly items of clothing:

woollen gloves and mittens, plus the ever-welcome balaclavas, which

were going to be so needed in the coming winters. Sometimes there

would be a bulk issue of scarves, gloves, socks, etcetera and

frequently there would be a note from the knitter, inviting a reply.

I wonder if any permanent attachments ever came from the rationed

reply letters.

As I have written, the civilian workers numbers

dwindled and a day or two after finishing with Firma Winkler our

room was told off to work for the Firma Best and once again Andy and